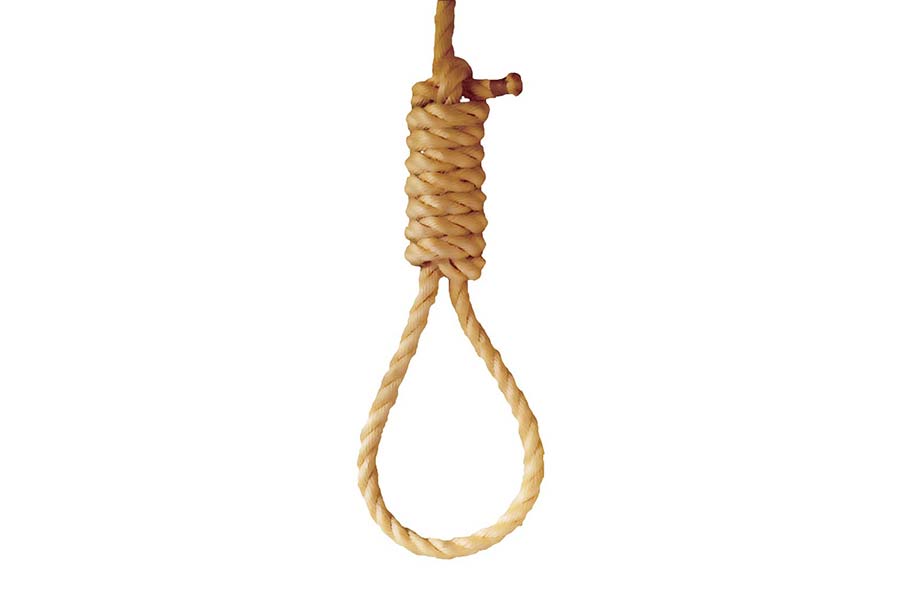

The gruesome incident in Kathua in which a minor was kidnapped and brutally gang-raped has pushed the government to issue an ordinance that makes capital punishment mandatory in the rape of U-12 minors. In this backdrop, Masood Hussain tries to trace the evolution of hanging as a punishment in Kashmir

There were 22 boys, Kashmir’s most known raconteur, Zareef Ahmad Zareef remembers as if it was yesterday. “We were rounded up by the police and held responsible for pasting posters on the walls,” he said. “We all were in the Central Jail Srinagar.”

Also jailed was a soldier, a resident of Gurgaon. He was an atheist and he had killed some of his colleagues and had faced the law of the land. He would make interesting speeches to us but the one he made for the last time was impressive and I still remember it, Zareef said. “He prayed for our Azaadi and was pretty emotional because he was to be hanged a day later.”

The jailers also told the inmates that the man is being hanged and preparations have started. “For three days prior to the hanging the hangman would come and make preparations,” Zareef said. “I watched him making the preparations, getting the rope, using various oils, pulling and straightening it and finally wrapping it around the pole.” The public executioners’ real name was not known but the jailers would know him as Beadh Watul. “He was residents of either Shopian or Kokernag and I remember the jail staff telling us that his family was in the profession of public execution for at least three generations, right from the Maharaja era.” An execution would fetch him Rs 50 and many other things.

“It was the intervening night of June 15 and 16, 1965, that the jail staff told us that we will not be permitted to move out during wee hours,” Zareef said. “That morning the soldier was hanged and we were permitted out only around 8 am.”

Death by hanging has been a penalty for various crimes and it was in vogue for centuries together. In fact, every summer would witness a couple of hangings for most of the Sikh, Afghan and Dogra era.

“I saw the body of a man hanging to a tree, apparently executed that morning. I asked who he was, and why he had been hanged, but all the passengers seemed so indifferent to the spectacle that no one knew more about it than myself,” Victor Vincelas Jacquemont wrote in his April 23, 1831 dispatch from Kotli (now in PaK). On May 15, he wrote again from Sheikhbagh in Srinagar: “There were a dozen suspended on trees near my camp (Sheikhbagh Srinagar), on the banks of the river. When the governor visited me, he told me, with a very careless air, that in the first year of his government he had hanged two hundred, but that now, one here and there was sufficient to keep the country in order.”

The death penalty was continued by Dogras as well. Public hanging has remained the most chosen option with the despots because they loved ‘object lessons’.

“I went out this morning in my boat, and we sailed towards the open plain beyond the precincts of the city, where two gibbets were standing, garnished by horrible squelettes of men in chains hanging, propped up (by wires) in wooden cages,” Mrs Havery wrote in her The Adventures of a Lady in Tartary, Thibet, China, & Kashmir: With an Account of the Journey that was published in 1853, not many years after Kashmir was sold to the Dogra chieftain Gulab Singh. She lived in Sheikhbagh in August 1853. “Their clothes were still on them, and these ghastly skeletons looked very revolting, bleaching in the bright sunlight. They have been hanging for two or three years; their crime was murder. The family of one of the two lives close by.”

It was much later that the hanging noose moved from public squares into the jails. But Zareef says there was not any hanging in Srinagar after 1970. “The last person who was hanged to death was Wahab Tabardar, a resident of Khanyar,” Zareef said. “He was convicted for the killing of a tourist in Dalgate’s Embassy Hotel.”

While he was killed for the murder, Zareef says the fate was sealed by his conduct and everybody was praying for his death. The reason was his notoriety in disturbing people when they would use public toilets! “Since then, I do not remember any other hanging in Kashmir,” Zareef said. But one person was hanged in Jammu somewhere around 1988.

In between, there was a major hanging that was executed in Tihar jail. It was that of JKLF co-founder Maqbool Bhat that took place on February 11, 1984. The death penalty was awarded by a district and sessions judge in Srinagar, Neel Kanth Gunjoo. It was executed in Tihar jail and the black warrants were actually signed by the then Chief Minister.

Though the death penalty was awarded to Bhat in case of a police man’s murder, the fact is that the execution was political in nature. This hanging was a key factor in changing Kashmir altogether. Even the trial court judge was assassinated by JKLF after the militancy broke out in Kashmir.

Afzal Guru was hanged on February 8, 2013, in the same jail and his corpse was also not returned to his family. Though he was a Kashmiri, his trial and the offence in which he was convicted took place in Delhi.

But the death penalty is constitutionally and legally valid. In murder cases and even in rarest of the rare cases of sexual violence, trial courts do award death penalties. It is only during the appeals that the superior courts convert the death penalties into life imprisonments.

The capital punishment is back in debate after the state government issued J&K protection of children from sexual violence ordinance 2018 that makes capital punishments mandatory in cases of rapes of minors, below the age of 12. The ordinance, expected to become a law in the next assembly session, denies bail to the accused, offers an in-camera trial to the victim, gives two months to the investigators and six months to the trial court. The onus of proving innocence is now on the accused. The punishment for sexual offences against women between 13 to 60 years stands enhanced to 20 years or life imprisonment.

The ordinance was issued in wake of massive public reaction over the abduction, gang-raping and murder of an eight-year-old Kathua girl by a group of people who wanted to scare away the microscopic Muslim nomadic minority from their area. The case brought India into instant disrepute as the case was globally reported and even commented upon by United Nations and the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

The ordinance has been generally welcomed by the lawyers and the commoners. “I support it and in fact I want it to be severe,” Sana Din Majid, a junior advocate said. Her colleague Siyaab Samaira added: “It should be a public hanging so that deterrence is created.”

“The criminality in Kashmir is negligible because there is thrust on moral education as part of the upbringing,” leading lawyers Zaffar A Shah said. “But enhanced punishment in such heinous crimes is a welcome step.” His colleague Mohammad Ishaq Qadri, who was the advocate general of the state for six years, said the ordinance was delayed.

But the difference of opinion is there. A major section of the practitioners of law insists that the new law will continue to be as useless as the earlier one if the state government fails to take the prosecution lightly. “It is good that timelines are there but it is more important that there are competent people in investigation and prosecution who will take these cases seriously in the special courts,” Shah said. “The absence of all these things had made the convictions the lowest ever.”

Even a High Court judge told a gathering of police that he was personally shocked after going through a case file in which a woman was raped nine times by three men and still the accused was seeking bail. He said the prosecution was weak and vague.

A small section of lawyers, however, insist that the ordinance was not required. “The existing law is competent enough to tackle and even award death penalties in rarest of rare cases,” Syed Faisal Qadri said. “The problem is that there is a lax investigation and the accused get away because there are loopholes.”

Recently during an address at a police function, High Court judge, Justice M K Hanjura, mentioned a case of 13-year-old girl who was sexually exploited repeatedly.

“A few days back, I went through a case of a girl child who was gang-raped for 22 days. When I went through the file, I realized how the prosecutor had identified the girl while recording the statement,” said Hanjura.

Ironically, her statement was recorded three days before the accused filed application for bail in the court. The police officer had deliberately suppressed the fact that she was exploited for 22 days. “The prosecutor too concealed this fact, although he had identified her in the court. With the result, the judicial magistrate going through the case had also not taken note of it,” lamented Hanjura. “There was a hue and cry over the Kuthua incident. But such matters are not prosecuted properly.”

Debate will continue. The global human rights watchdogs that have been against the capital punishment, throughout have started their campaign against the ordinance. But the fact is there are two cases of brutal rapes of minors in Kashmir which are going through the appeal. In both cases, the trial courts have awarded death penalties.

Soon, there will be infrastructure issues. Right now, district jail in Jammu is the only place across the state where the hanging pole exists. All other jails have undone the noose as hanging was out of fashion. Has the circle of history, made a restart?

from Kashmir Life https://ift.tt/2FB7RwU

via IFTTThttps://kashmirlife.net

No comments:

Post a Comment