In the Jammu and Kashmir’s downgrade to a Union Territory, most of the autonomous Commissions were closed down. These included the Commission for Women. Saima Bhat met some of the women who are desperately keen to know what happens to their cases that the closed Commission was hearing

Art Work by Malik Yasir

Living with domestic violence was ‘the way of life’ for Shahzada, a mother of two kids. The humiliation and pain crossed the threshold when she was allegedly set afire by her husband and in-laws. Somehow, she survived. After nursing her wounds for a few weeks at Srinagar’s Shri Maharaja Hari Singh (SMHS) Hospital, she finally gathered her courage to file a case with Jammu and Kashmir State Commission for Women and Child Rights.

Two days after filing the case, when Shahzada visited the Commission office at Bemina to know the status of her complaint, she found its gate locked and the commission closed, literally.

“It took me a decade to speak up for my rights because I always wanted to save my marriage so that my kids don’t have to live without their mother or father,” Shahzada regretted. “But unfortunately when I got the courage to face my fate, my only hope, the women’s commission, was closed down.”

Shahzada is one of around 220 women who had their lives linked with the commission. They expected justice as their cases were under different stages of persuasion but the Commission locked its doors in wake of the abrogation of the Article 370 and the change in status of Jammu and Kashmir to a Union Territory (UT).

When Shahzada was allegedly set afire, she said, she was taken to the district hospital in Kupwara where doctors referred her to the SMHS hospital in Srinagar because her condition was not good. “For two days my family was not informed,” she alleged. “Then nobody from the local police station visited me to record my statement.”

Her parents allege that their son-in-law and his family used to harass her from the initial days of her marriage. “She is living with this harassment for the last 10 years,” one of her brothers alleged. “Every time Shahzada was sent back to us, we used to make some reconciliation between the couple to save the future of their kids. But now we cannot think of even sending her back. There is no guarantee if they will not attempt to kill her again.” It was her brother who accompanied her to the Commission. Quickly, after receiving the complaint, the Commission issued a notice to her husband and his parents. Well before they could respond, the Commission ceased to exist.

Vasundhara Pathak Masoodi, Commission’s last chairperson, said the order for the closure of the Commission reduced their powers and none of the accused found it necessary to respond to the Commission’s directions.

Art Work by Malik Yasir

After August 5, Vasundhara converted her official residence into her office so that the women don’t have to suffer because of the situation. “I didn’t want the Commission to die before its death,” she said. “Our office was in Bemina but it was inaccessible to the women coming from far flung areas of Jammu and Kashmir. So I started to work from my residence in Tulsi Bagh, which was accessible.” After the Commission’s authority ceased on November 1, 2019, Vasundhara, took the first available flight to Delhi and resumed her work as a lawyer. A Supreme Court lawyer, she had taken over the leadership of the Commission in July 2019.

In Delhi, though, Vasundhara is still not disconnected from Kashmir. She said she is still getting calls, mails and text messages from the complainants who seek her advice and suggestions about what they should do in absence of the Commission. The Commission was one of the seven other Commissions that ceased to exist after the Jammu and Kashmir Reorganisation Act, 2019, was implemented in Jammu and Kashmir. The law promulgated by the Parliament retained 166 state laws, repealed 153 and implemented 106 Central laws with certain changes. The Commissions’, which became history, included the State Human Rights Commission, Commission for Persons with Disability, Information Commission, Consumer Commission, Women and Child Rights Commission, Accountability Commission and Electricity Regulatory Commission.

Interestingly, these Commissions were closed down immediately after the General Administration Department (GAD) issued an order on October 24. The order asked the staff of these Commissions to rejoin their services at their parent departments. But going through a Presidential order, which came after GAD order, these Commissions should have continued their working, many believe.

“All the Commissions should have continued but the irony was that the closure order came before that Presidential order,” a lawyer, wishing anonymity, said. “Section 17 of that order, passed by the President of India, reads the salutatory bodies deemed to have continued till the new UT administration should have taken over. It is kind of legal infirmity.”

Sections 91, 93 and 95 of the Jammu and Kashmir Reorganization Act reads that “every person who, immediately before the appointed day, is holding or discharging the duties of any post or office in connection with the affairs of the existing State of Jammu and Kashmir in any area which on that day falls within one of the successor UT shall continue to hold the same post or office in that successor UT, and shall be deemed, on and from that day, to have been duly appointed to the post or office by the Government of, or other appropriate authority in, that successor UT. And, provided that nothing in this section shall be deemed to prevent a competent authority, on and from the appointed day, from passing in relation to such person any order affecting the continuance in such post or office.”

After going through the Act, Vasundhara also believes that the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) was perhaps kept in dark. Otherwise the Centre would not have come up with the Presidential order, she said.

The Commission was busy when the closure order came. Early October when most of Jammu and Kashmir was still in sort of a communication blockade, the Womens’ Commission got some information about the murder of a woman in Udhampur’s Mantalai belt. “There were apparent marks of torture on the body of the slain lady but the police did not register the case as per the prevalent provisions,” Vasundhara said. “It registered a case of a normal death.”

The Commission on October 14, when mobile services were resumed sent a notice/a summon to the concerned SP through SMS. “The officer couldn’t send me the required ATR of the case as next day the SMS were banned in the region again,” Vasundhara said. This landed the lady’s parents in a serious mental agony. “Her father calls me every day and says he and his wife are left with no option other than to commit suicide.” She said that she could request the concerned police official in her personal capacity to visit the family but the police are under no obligation to oblige her.

From its inception in 2005, the Commission had expanded its jurisdiction from domestic violence to many other areas including the cases under sexual harassment, labour laws, harassment at work places, social enactments against women and children. It, however, was always crying to seek some attention as it was at the back burner of erstwhile state’s priority.

The Commission was set up under the leadership of Dr Girja Dhar, a renowned gynaecologist, who earlier headed the Government Medical College in Srinagar. National Conference lawmaker from Haba Kadal, Shameema Firdous, succeeded her. After the lady was removed, the Commission remained headless for seven long years.

The regime change brought in a new political appointee, Nayeema Ahmad Mehjoor, an erstwhile BBC broadcaster. Being a political appointee, she was one of the many political workers holding office, who resigned after the BJPDP coalition crumbled under its own weight in 2018 summer.

In July 2019, when the state was being ruled by Satya Pal Malik, the Commission got a professional, Vasundhara Pathak Masoodi, as its leader. Her takeover had sent positive vibes around at a time when the issues linked to children were drawing a good attention.

During all these years, the Commission registered around 3500 cases of which only 220 were still under process. Of these 220 cases, an official said that at least in six cases the Commission was going to reach conclusion in the same week when it ceased to exist. As the specific cases were moving to the Commission, this had started easing the load on regular courts.

The complainants believe that the Commission was a key facility for them as they could represent themselves, plead their own cases and did not require any cash. “Neither lawyer was needed nor money for filing the cases,” one complainant, a resident of Lasjan, in city outskirts, whose case was solved through counselling in just two hearings. “I can say that the preamble of this Commission was that they wanted to reconcile the two parties through counselling. They were against divorce.” After some conjugal tensions, she gives credit to the Commission for living happily with her husband. She is proud mother to a kid after the Commission helped her settle her conjugal issues.

The early snowfall in November engulfed the apple orchards in gloom. So was Mehmooda, who lives in one of the villages of Anantnag.

Mehmooda was married last year with Arshid, who was employed in the Middle East. Her parents were happy that they chose a better match for their daughter in comparison to her cousins. Soon after, Mehmooda shifted her base with her husband and started weaving dreams of her new life, the happiness proved short lived.

As Mehmooda was going to start her new life at a new place, she came to know that she was her husband’s third wife. Initially, it was difficult for her to accept the reality but soon she decided to accept her fate.

After a year, Mehmooda and Arshid came Kashmir for holidays. Here, Arshid “dumped” her to his parents with a promise that he will return. Instead Arshid went to Bangalore to reconcile with his second wife.

Mehmooda continued living with her in-laws thinking that Arshid will return. The situation was quite tense. Soon, she alleged that her in-laws started harassing her. One day, she finally left with no option than to reveal the secret to her parents.

The family filed a case with the Commission and a notice was served to her in-laws through police. “Initially, her father in-law responded well to the notices and was willing to get his son back but when the news of the closure of the Commission spread he stopped appearing before the Commission,” said Vasundhara.

Soon after that the Commission received the news that Arshid was going to fly back to Gulf. The Commission sent a letter to the Regional Passport Office (RPO) so that he cannot leave the country. They could not stop him, however. As per Vasundhara, Mehmooda keeps calling her that she is left with only option: suicide.

Mehmooda has been advised to go to a regular court.

Vasundhara asserted that the Commission was the only hope for the women of the Jammu and Kashmir, which was a better platform than the regular courts where cases take even decades to get solved. “Most of the women were financially unsound,” she said. “The Commission also gave them the leverage to speak for themselves unlike the regular courts where they had to hire their lawyers.”

The society in Jammu and Kashmir can ill-afford absence of such an institution for long. This is despite the fact that the crime rate against women, as per the Jammu and Kashmir Police, showed a decrease in 2019 in comparison to 2018.

Under Construction building of JK State Women’s Development Corporation Bemina Srinagar

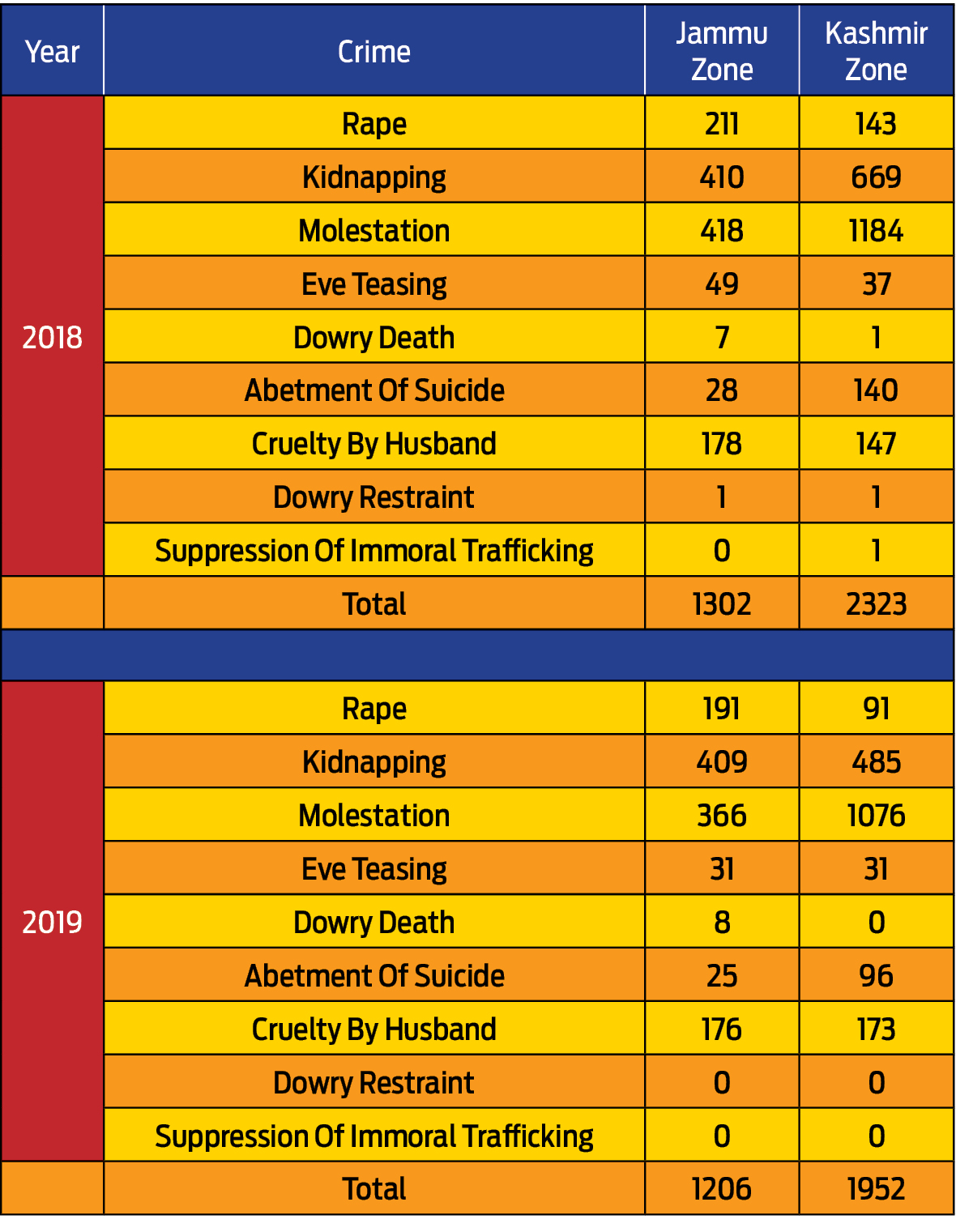

In 2018, a total of 3625 cases under different sections of crime against women were reported from across Jammu and Kashmir. These included 1302 cases from Jammu zone and 2323 cases from Kashmir Valley.

In 2019, in comparison, only 3158 cases were reported from Jammu and Kashmir, including 1206 cases from Jammu and 1952 cases from Kashmir. But the officials working with various departments and taking care of the crimes against women believe the figures could be higher as reporting these crimes was very difficult between August, and October, owing to restrictions.

Though lacking any comparison with the Commission, the government has another complaint redressal mechanism on the women’s front: Sakhi-One Stop Centers (OSC) for the women of Jammu and Kashmir. But since August 5, the officials at their Srinagar centre claim they are not satisfied with their work which has been hugely affected by the clampdown, communication blockade and then by the ban on the internet.

“We resumed our work in September only but when there was a clampdown on communication channels including phones and internet how could we have continued our work which is based on a helpline number,” said Syed Ruksana Alam, the OSC Coordinator in Srinagar. “We used to come office so that if victims visit us, we might be able to do something.”

Ruksana claims that the redressal mechanism for women was set up to empower women and to extend help if they are in distress.

“OSC’s chairperson is the district commissioner but he remains busy with the law and order situation these days and we have never met one to one,” said Ruksana.

Since October, Ruksana alleges that she has requested the administration to restore the internet to their office so that they could help women but they were never given any attention.

As Ruksana was speaking to this reporter, she was visited by a lady, a mother of a two years old daughter. “Soon after telephones were restored we got a case of this lady whose husband was threatening to rape his own minor daughter,” Rukhsana detailed the visiting lady’s crisis. “We were following this case for more than a month now but due to the ban on internet we couldn’t record her case on our data base so we had to call her to our office so that we could record her statements.” In this particular case she says the father has been booked under POSCO because he had already tried it once.

The lady claims her husband was having an extra marital affair. “He wants to leave me but I did not permit it,” she alleged. “He was threatening to rape our minor daughter so that I leave from his house. Initially, I thought he is just threatening but then he attempted it.”

Vasundhara Pathak Masoodi

As on date 1370 cases remained registered with the OSC’s Srinagar office.

Now, as the State Commissions have winded up and the cases are not referred to any national commissions, the secretaries of these commissions were directed, through government orders, to send the case files and records to the concerned administrative departments. All the record files of the Women’s Commission have been sent to the UT’s Social Welfare Department.

“Yes, we have received piles of records from the Women’s Commission but we are not in a position to tell you what has to be done,” one officer, who agreed to talk on the condition of anonymity said. “We are caretakers of these files, rest we have nothing to do with the cases.”

from Kashmir Life https://ift.tt/38SFzNr

via IFTTThttps://kashmirlife.net

No comments:

Post a Comment