by M J Aslam

Any argument against Article 35(A) of the Constitution of India in isolation from the political and social conditions in which partition of India, accession of Jammu and Kashmir with India took place and in which Orders and Notifications of 1927 and 1932 were issued by the then Ruler Maharaja Hari Singh is patently bound to lead to wrong conclusions about it.

Pre Partition History

Let us briefly revisit the history and promulgation of the Order and Notifications of 1927 and 1932 issued by Maharaja Hari Singh. The main objective behind those Orders and Notifications was to address certain concerns that were raised and brought to the notice of the then sovereign Ruler. The people from erstwhile Punjab had started getting jobs in the government departments and purchasing land from the locals of the state at an ever-increasing scale. Feeling alarmed and threatened by the foreign intrusion into their homeland and likely trampling over their rights of employment and property, the residents of the state, predominantly non-Muslim (Dogras of Jammu and Kashmiri Pandits), were the main opponents and “objectioners” to the “foreigners” likely going to change state’s demography and officialdom.

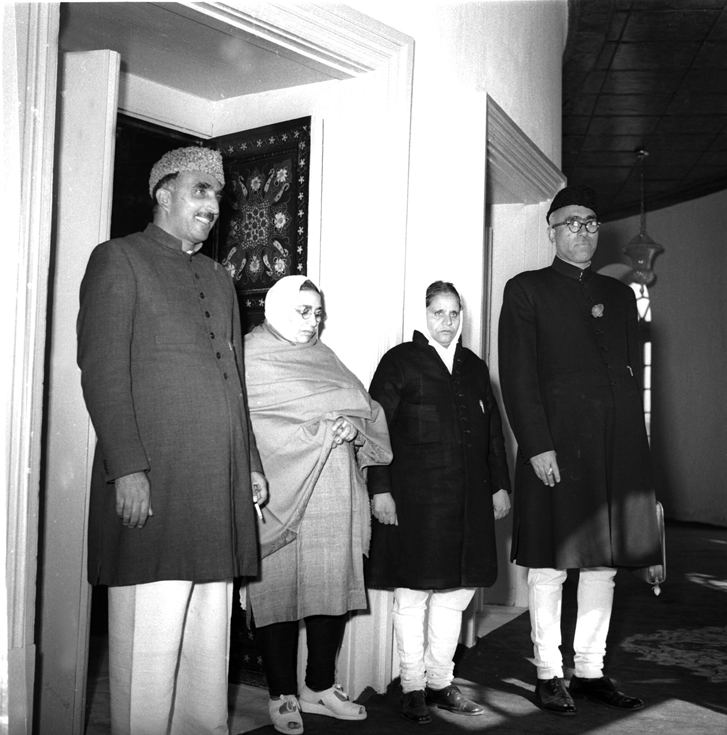

Sheikh Mohammed Abdullah and Ghulam Mohammed Bakshi with Mrs Iswari Devi Maini and Mrs Rajender Singh, women-members of the Kashmir Constituent Assembly. Photograph taken before the inauguration of the Assembly in Srinagar on October 31, 1951.

“The alienation of the Kashmiris from Hari Singh was heightened by the continuing presence of ‘outsiders’ in government service, which led to a movement known as ‘Kashmir for the Kashmiris’, sponsored by the more educated Kashmiri Pandits. …”. (“Kashmir in Conflict” by Victoria Schofield, [2013] page 17) Hearing the voices of concern and addressing the same, the King got a “statutory” order defining “Hereditary State Subject” and recognized the “Hereditary State Subject’s” exclusive rights of appointment in the government departments and the purchase and sale of land. The Order was passed to forbid the employment of non-State subjects in the public services besides disallowing them to purchase land in the state of Jammu and Kashmir. (Ibid) In simple words, such rights were not available to non-state subjects.

The said Order was, by implication, replaced by the Notification 1-L/84 dated 20-04-1927 whereby the term “State Subject” was substituted for the term “hereditary state subject” and the State Subjects were divided into several categories, the discussion about whom is beyond the scope of this article. The Notification 1-L/84 dated April 20, 1927, was followed by the Notification No 13/L dated June 27, 1932, under the Command of the Sovereign with a view to determine the status of the State Subjects in a foreign country and to inform the Governments of the foreign countries about the position of their (foreign) nations in the State. Jammu and Kashmir.

Maharaja Hari Singh

So, to adumbrate the facts, the Notifications of 1927 and 1932 granted to the State Subjects exclusive rights of (1) scholarships, (2) land ownership and (3) recruitment to State Services. (State of Jammu and Kashmir vs Dr Susheela Sawhney, AIR 2003 JK 83 = (1) JKJ 35) The Notifications of 1927 and 1932 were protected under the earlier Jammu and Kashmir Constitution of 1939 which were further protected and preserved under the Jammu and Kashmir Constitution of 1956 (Sections 5-A to 5-F).

If we move further back towards the end of 19th century Kashmir, we will notice that a deep concern was also expressed by the Principal Settlement Officer of the State of Jammu and Kashmir in 1887 against possible exploitation of land rights of Kashmiris by others if statutory protection was not granted to those rights of the Kashmiris by the monarchs of that day. (The Valley of Kashmir, (2014), Sir W P Lawrence, pp. 430-432)

The discussion so far brings us to conclude that afore-mentioned special rights and privileges of the people of Jammu and Kashmir with respect to their (1) immovable properties, (2) government jobs and (3) scholarships are firmly grounded in the pre-partition days of the state.

Post Partition Follow Up

India got freedom on August 15, 1947, immediately on cessation of British paramountcy under the Independence Act, 1947 wherein 600 odd States of united India were left free to choose between either of the two Dominions of India or Pakistan created thereunder. Almost all States [of the Indian Union]decided to accede to Dominion of India except the State of Jammu and Kashmir. The Ruler of Jammu and Kashmir Hari Singh took time to decide either way till “special circumstances” that had already started showing signs of coming, ultimately came when on October 26, 1947, the Maharaja entered into an Instrument of Accession (IoA) with India. The IoA provided for “conditional accession” of Jammu and Kashmir with India on three subjects only, namely, Defense, Foreign Affairs and Communication.

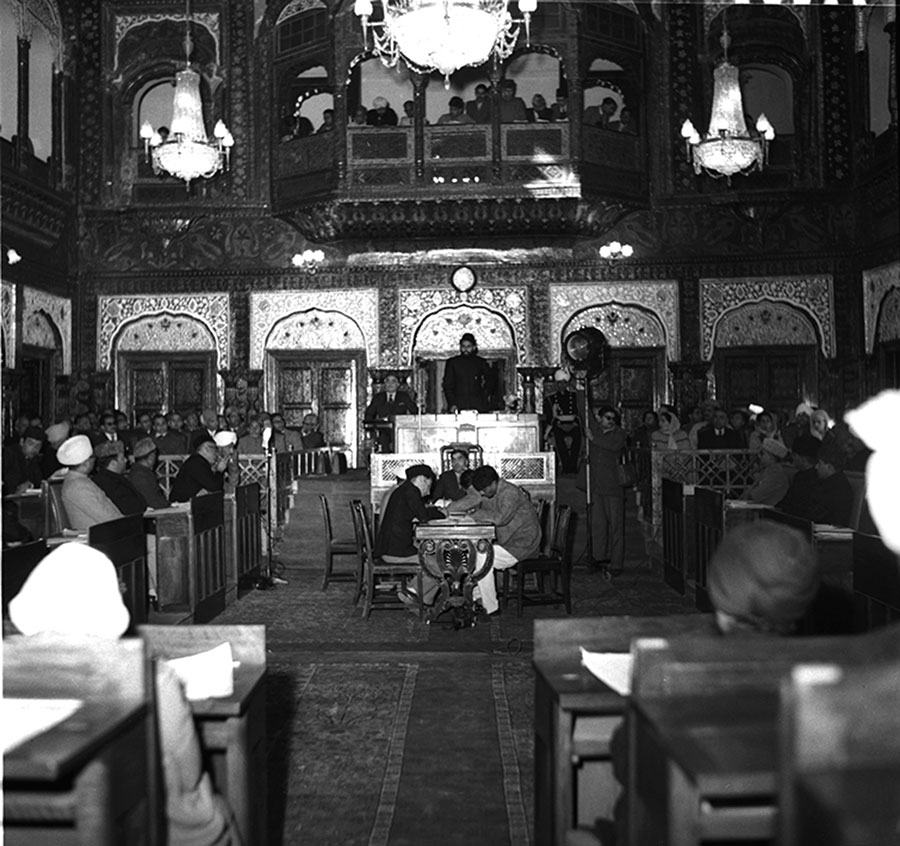

Maulana Mohammed Sayed Masoodi Provisional President of the Kashmir Constituent Assembly addressing the members on the inauguration of the Assembly in Srinagar on October 31, 1951.

The Dominion of Pakistan did not accept the said “conditional accession” and ultimately the matter was taken to the UN by India itself in January 1948 for a final verdict. The UN General Assembly passed several resolutions upholding the right of self-determination of the people of Jammu and Kashmir, as a concomitant of democracy, under UN auspices in the state.

In the meantime, during a period of almost three years, from December 9, 1946, to November 26, 1949, the Constituent Assembly of India was busy in drafting, deliberating and discussing the provisions of the future Constitution of Republic of India. It was finally adopted on November 26, 1949, and came into effect from January 26, 1950. The Constitution under Article 394 extended to the whole of India. It is manifestly clear that it did not by its own force apply to Jammu and Kashmir in the same way as it applied to the rest of India. It was extended to Jammu and Kashmir by virtue of two provisions only viz Article 370 and Article 1.

Article 370 incorporated three items of IoA empowering Parliament to legislate on them only as far as Jammu and Kashmir was concerned. Regarding other matters and provisions of the Constitution, under Article 370 (1) (d), it was /is laid down that only the President could extend them (other provisions of the Constitution and Parliamentary Laws on such matters in Union and Concurrent lists on which the Parliament has the power to make laws), with such exceptions and modifications as he may specify by order, to the State of Jammu and Kashmir.

However, this special process of applying Constitution to the State is required under Article 370 to be completed only by an order passed/to be by the President in concurrence or consultation with the State Government.

As noticed above, to confront challenges in UN GA questioning legality of India’s claim on Jammu and Kashmir, the Constitution (Application to Jammu and Kashmir) Order of 1950, which was concomitant with the Constitution itself, tried to formalise and legalise the relationship between the State & Union of India. But, it was not found enough for a “constitutional democracy” like India to justify its claim on Jammu and Kashmir on Articles 370, 1 & Constitution (Application to Jammu and Kashmir) Order, 1950. So, discussion for further strengthening bonds of relationship, bringing Jammu and Kashmir constitutionally closer to India continued between India leaderships and Jammu and Kashmir which culminated in what is popularly called Delhi Agreement of 1952 signed between Sheikh Abdullah and Pandit Jawahar Lal Nehru.

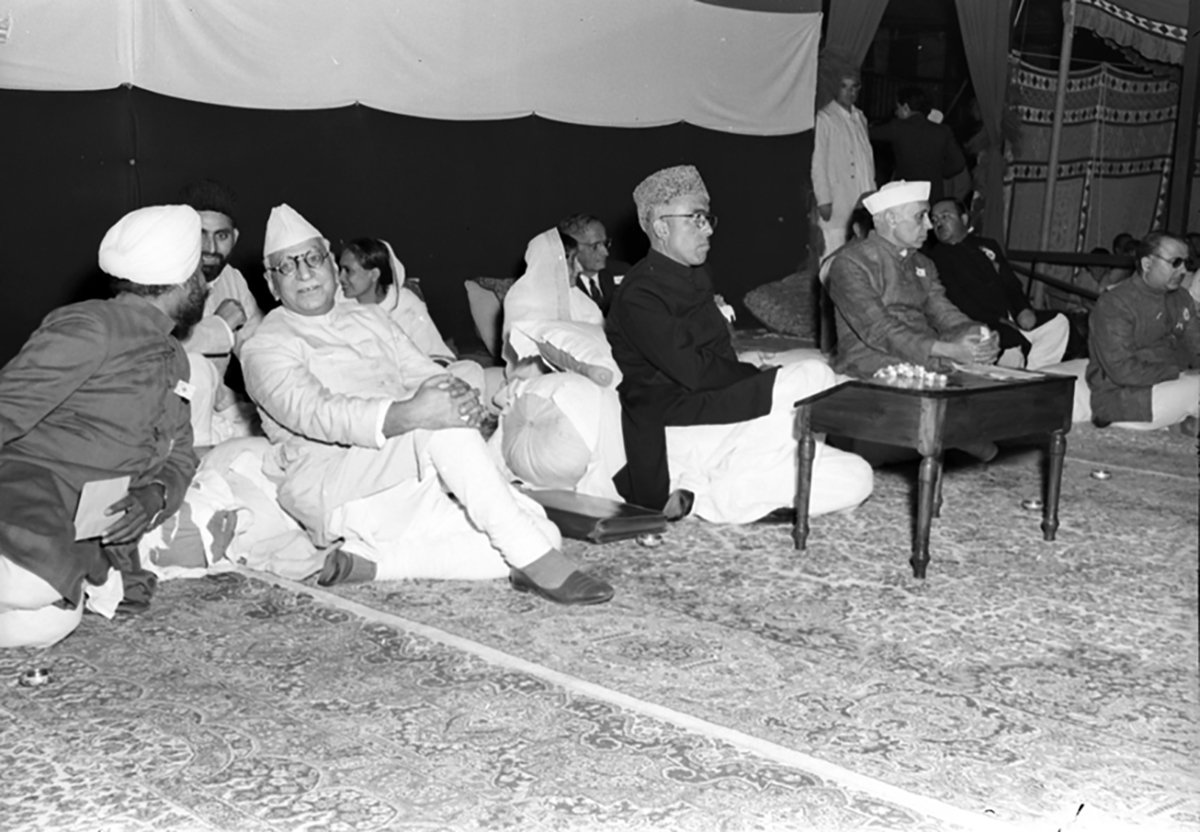

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah, Rakumari Amrit Kaur and Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, Deputy Prime Minister of India during the proceedings of the annual meeting of the National Conference at Srinagar on September 24, 1949.

In other words, one can say that Delhi Agreement, despite criticism it bore from the Hindu RSS hardliners of Jammu and Kashmir and India, provided the much-needed remedy to India to assuage its immediate trouble at the international level by crawling along the constitutional path to reach closer and closer to Jammu and Kashmir.

Point Two of the Delhi Agreement is pertinent in the context of the discussion and it is writ large from this point that citizens of Jammu and Kashmir were not regarded as citizens of India and so, it was agreed that Article 5 of the Constitution of India would be extended to Jammu and Kashmir to include the people who have a domicile in Jammu and Kashmir to regard them as citizens of India. Point Two of the Agreement further empowered the state legislature to make laws of its choice defining “State Subjects” and confer on them the privileges and rights which they have had been enjoying already by virtue of Orders and Notifications of 1927 and 1932.

The Delhi Agreement was a solemn pledge made between Jammu and Kashmir and India and any backtracking on it by Sheikh Abdullah was to be treated not in India’s “national interests” refer letter dated June 10, 1953, of KN Katjoo addressed to Nehru and India through its leadership had equally bound itself to incorporate its terms in its Constitution and wanted Jammu and Kashmir to do the same through its future Constituent Assembly. Refer reply of Nehru to Dr Karan Singh’s two letters dated August 3, and August 7, 1952.

The question arises if backtracking by Jammu and Kashmir, Sheikh Abdullah, from the points of the Delhi Agreement was unacceptable to India, then, by the same logic reneging by India after 70 years on any of those terms including Point Two is equally unacceptable to people and all leaders of Jammu and Kashmir except few RSS ideologues who are a fringe minority.

Delhi Agreement In Action

In the backdrop of the Delhi Agreement of 1952, followed by the recommendations dated February 6, 1954 of the Jammu and Kashmir Constituent Assembly‘s Advisory Committee on Fundamental Rights and Citizenship and Nehru’s Statement to the Lok Sabha about Delhi Agreement, the President of India, in exercise of his powers conferred upon him by Article 370 (1) with concurrence of the Government of Jammu and Kashmir, passed the Constitution (Application to Jammu & Kashmir) Order, 1954.

The said Presidential Order of 1954, thus, implemented the Delhi Agreement whereby, among many other things, Indian citizenship was extended to the residents of Jammu and Kashmir and simultaneously Article 35-A was inserted into the Indian Constitution that gives carte blanche to the State Legislature to define who are the “State Subjects” and confer on the “State Subjects” special rights and privileges in public sector / government jobs, acquisition of immovable property in J&K, settlements, scholarships and other public aid and welfare. Article 35-A is reproduced below:

“Saving of laws with respect to permanent residents and their rights, n Notwithstanding anything contained in this Constitution, no existing law in force in the State of Jammu and Kashmir, and no law hereafter enacted by the Legislature of the State:defining the classes of persons who are, or shall be, permanent residents of the State of Jammu and Kashmir; or conferring on such permanent residents any special rights and privileges or imposing upon other persons any restrictions as respects—employment under the State Government; acquisition of immovable property in the State; settlement in the State; or right to scholarships and such other forms of aid as the State Government may provide, shall be void on the ground that it is inconsistent with or takes away or abridges any rights conferred on the other citizens of India by any provision of this part”.

It may be mentioned that the Constituent Assembly of the State of Jammu and Kashmir subsequently following the Delhi Agreement and Article 35-A made provisions relating to “permanent resident” by inserting sections 5-A to 5-F in the Jammu and Kashmir Constitution of 1956.

Word of Caution

To iterate, the geopolitical conditions of Jammu and Kashmir were very much in the knowledge of the lawgivers. Taking due notice of the same, the lawgivers did not apply the Constitution to Jammu and Kashmir simultaneously with other States. To circumvent or surmount those hard geopolitical facts that obtained in UN General Assembly and UN Security Council, a mechanism was devised in the shape of Article 370 to link Jammu and Kashmir “constitutionally” with India. This provision was based on a pact between the Indian State and Jammu and Kashmir, the governors and the governed, whereby the governed (general masses of the state) had agreed to be governed by the governors but strictly on the condition that the age-old natural rights of the governed shall be protected and preserved at all costs, which the people of Jammu and Kashmir shall never be deprived of.

This was and is a solemn pledge made by Indian State with the people of Jammu and Kashmir. This is the universally accepted political theory. “The Presidential Order of 1954”, which is an offshoot of Article 370 “implies both further strengthening of India’s hold on Kashmir and recognition of a privileged position of Kashmir within the Indian Republic”. (Josef Korbel: Danger in Kashmir (1954), pp. 246-247) If India de-recognises or snatches the “privileged position of Kashmir”, at least in its remnant of Article 35-A, its hold on Kashmir will get loosened further as Kashmiri pro-Indian leaders have publically declared that if Article 35-A is abrogated, there will be nobody to hold tricolour in Kashmir. Ram Jethmalani, noted Supreme Court lawyer, has indirectly conveyed a similar word of caution to Sangh Parivaar think tank about misadventure of supporting “indirectly” the people (their proxy petitioners before the SC) who are hell-bent on abrogation of Article 35-A to change the demography of Jammu and Kashmir from majority-Muslim-State to its minority State.

Tailpiece

In the light of foregoing, if Article 35-A is tinkered with, it will open Pandora box and Jammu and Kashmir’ss relation with India will constitutionally, morally, socially and historically come in serious doubt. It is not Article 35-A alone but a plethora of Articles of Indian Constitutions that were transferred to Jammu and Kashmir vide Presidential Order of 1954 brought in question before the Supreme Court by We the Citizens.

(Views expressed here are personal & not of the organisation the author works for. M J Aslam is author, academician, story-teller and freelance columnist. Presently AVP, JKB.)

from Kashmir Life https://ift.tt/2PM00Tn

via IFTTThttps://kashmirlife.net

No comments:

Post a Comment