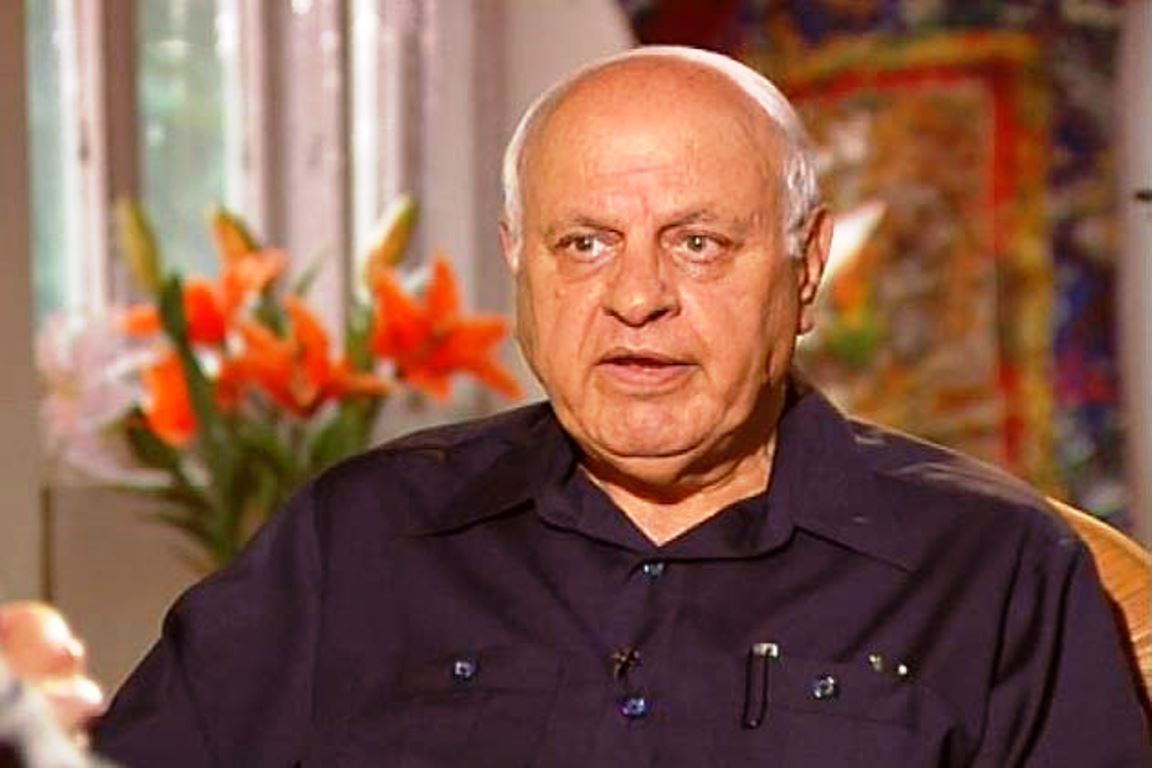

For four decades the five-time Chief Minister has dominated Kashmir’s pro-establishment politics with his most prominent political function being to champion Delhi’s cause in a region roiled by a long-running armed separatist movement and claimed by Pakistan. But then being a pro-India leader in Kashmir doesn’t entirely define Abdullah, writes Riyaz Wani

As early as 2018, National Conference president Dr Farooq Abdullla threatened to boycott all elections if concerns over Article 35A are not addressed.

When Farooq Abdullah didn’t speak in parliament on the revocation of Article 370 (he later said he was not given time), it greatly upset Kashmir. People slammed him for letting down Kashmiris after raising expectations as head of the six-party alliance that passed Gupkar Declaration calling for a reversal of the move undoing Jammu and Kashmir autonomy.

But the opinion changed when Abdullah’s interview with Karan Thapar surfaced. Here Abdullah was in his element. In his typical passionate style, Abdullah almost articulated almost everything that Kashmiris wanted to be said. Through his answers to Thapar’s questions, he drew an honest picture of the prevailing situation in Kashmir. When he said that Kashmiris would like China to rule them than India, he struck a chord with people. Similarly, he couldn’t have been more reflective of the sentiment when he said that Kashmiris were feeling like slaves under the existing circumstances.

4 Decades

For four decades Abdullah has dominated Kashmir’s pro-establishment politics with his most prominent political function being to champion New Delhi’s cause in a region roiled by a long-running armed separatist movement and claimed by Pakistan. But for seven months following the August 5, 2019 move that undid Jammu and Kashmir autonomy, Abdullah was put under detention along with other political leaders, a major part of it under Public Safety Act.

Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah with Pandi Nehru and Mrs Indira Gandhi. Mirza Afzal Beig and Dr Farooq Abdullah are also seen in the frame.

It was a bitterly ironic turn of events for the five-time Chief Minister who in and out of power had always batted for India in Kashmir, a stand he stuck to despite its unpopularity back home. He continued to do so after 1989 when he lost power following the outbreak of the militancy against Delhi’s rule. Delhi then desperately needed a well-known Kashmiri leader to stand by its cause. Abdullah was this leader, the biggest of them all. His support for India at the time compensated for the absolute lack of visible popular support for the country in the Valley. What is more, Abdullah’s backing of India brought with it the full weight of the legacy of Sheikh, his father, who until his death commanded a near-absolute following of his people.

In Geneva

Abdullah also came in handy to Delhi through the nineties to fight off the international scrutiny of the human rights situation in Kashmir. He was gainfully deployed across the world to defend India on Kashmir and blame Pakistan for the turmoil in the erstwhile state.

In 1994 when India was at the receiving end at UNHRC over its human rights record in Kashmir, Abdullah was flown to Geneva to defend the country as part of the team led by the then opposition leader Atal Bihari Vajpayee. The team had managed to fend off UNHRC intervention in Kashmir. Abdullah, according to reports of that era, had given a tough time to the persons in Pakistani side claiming to be Kashmiris by asking them “can you speak in Kashmiri?”

But then being a pro-India leader in Kashmir doesn’t entirely define Abdullah. Nor does being a Kashmiri Muslim leader. He would thrive in flaunting his secular credentials by singing bhajans at Hindu religious functions. He would let go at wedding parties and lip-sync and dance to Bollywood tunes. What is more, when Muslim leaders in India baulked at chanting Bharat Mata Ki Jai, arguing it was against their religion to do so, Abdullah went ahead and did it. He shouted the slogan loudest during an all-party prayer meeting last year for the former Indian prime minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee. And he stuck to his guns even when he was later heckled by people in Kashmir during Eid prayers for doing so.

Unpredictable

Abdullah has also been unpredictable and inconsistent in his political conduct, flitting between contradictory ideological postures with ease. He would pillory New Delhi’s Kashmir policy one day and the following day plead for bombing Pakistan out of existence for supporting militancy in Jammu and Kashmir. He would seamlessly traverse the distance from allegiance to his religion to a commitment to secularism to the praise of rightwing. And through it all, he not only escaped unscathed politically but went from strength to political strength. His statements would often shock his supporters and baiters alike but then it would soon turn out that Abdullah hadn’t been serious after all. Over the years Abdullah had perfected the art of elevating his inconsistencies and apparent flaws into an endearing political quality, something people would love and hate simultaneously.

File photo of Dr Farooq Abdullah, Omar Abdullah and Justice Hasnian Masoodi with PM Narendra Modi in New Delhi.

In past he has also heaped praise on Narendra Modi, then Gujarat Chief Minister, at one point even defending him soon after 2002 riots in which around 1000 Muslims were killed. In 2011, while addressing a gathering in Ahmedabad, Abdullah said he longed for the day when he would see Allah in Modi’s eyes and in turn Modi would see Bhagwan in my eyes. What is more, soon after Kashmiri militant Afzal Guru was hanged in early 2013, Abdullah said Guru had got a fair trial, overturning his son Omar Abdullah’s outrage over the execution.

Imprisoned

As the PSA against Abdullah made it clear, BJP’s Naya Kashmir has no place for him. Once extensive political middle ground in Jammu and Kashmir that flourished between proponents of the state’s integration with India and those for its separation from the country is dead. It was a space that produced leaders like Abdullah who could with equal ease owe allegiance to India and also relate to ongoing separatist movement by pressing for an acceptable political solution to the issue. They could also espouse their own settlement formulae which sought more political autonomy for Kashmir within India’s constitution. It is now a stark choice between reconciling to assimilation with India with the looming threat of a demographic change or resisting it, a choice in the words of the economist Haseeb Drabu between ‘being a stooge or a separatist’.

Dr Farooq Abdullah with his wife Molly Abdullah. KL Image by Bilal Bahadur

Will Abdullah be a stooge? He was often billed as one by his detractors in Kashmir and also by Pakistan but then he operated on a wider political canvas in a partially autonomous Kashmir, which allowed political space for debating and challenging Kashmir’s place within India. Mainstream politics in the state has suddenly become narrow and contracted which may not be for the likes of Abdullah.

A Contentious Legacy

Ever since his summary dismissal by the then Governor Jagmohan in 1984, Abdullah has loomed large over Kashmir politics. This despite the fact he has never been a popular leader in the true sense of the term. He never commanded a visible personal support base with people rooting for him. There has always been a degree of ambivalence in the way the people in the Valley have related to him.

In 1987, despite being in the wilderness for three years and despite carrying around him the image of being wronged by Delhi, the people were not ready to give him another chance. Instead, there was a groundswell of support for Muslim United Front forcing Abdullah together with his alliance partner Congress to resort to reckless rigging, a piece of baggage that he is still unable to rub off. This subversion of democracy became a compelling factor for the rise of the subsequent armed revolt. Abdullah’s rule was aborted again. He was forced to resign as New Delhi once again appointed Jagmohan, his bete noire as the Governor.

All-party meeting at residence of Dr Farooq Abdullah in anticipation of August 5, 2019 decision

Abdullah returned to power yet again in 1996 in an election which was, by and large, met with a blanket boycott. He began the term on a hopeful note, even breaking down through his oath-taking ceremony attended by the then Prime Minister Deve Gowda. Abdullah declared he was a changed man and pledged a reformed approach to governance. But nothing changed. He ran an inefficient roughneck administration mired in corruption that filled the atmosphere with fear by letting loose on the people the Special Operation Group (SOG). In the then all out face-off between the state and the people, Abdullah became the face of the government.

He had his moments, though: first when he passed the autonomy resolution in the Assembly. And second when he ordered the exhumation of the five innocent persons killed by Army at Pathribal and passed off as the terrorists responsible for the killing of 36 Sikhs at Chittisingpora. But this hardly detracted from the general callousness of his government and his personal indifference to the messy state of affairs to a point where he would often justify extrajudicial executions as a legitimate response to the prevailing situation.

By the time Assembly elections pulled around in 2002, people were already feeling choked and wanted Abdullah to go. This is how PDP broke on the scene. To its credit, the party made a redeeming difference in governance juxtaposing it seamlessly with political rhetoric that sought to appeal to the separatist sentiment in Valley. More objective measurement of this difference was a rise in PDP’s seat tally from the 16 to 21 in the subsequent 2008 polls, while as NC, despite being in opposition barely managed to retain its 28 seats.

A Fickle Brand of Politics

Abdullah introduced a brand of politics that was consistently inconsistent. He often fiddled with Kashmir’s troubled ideological divides and the rooted sentiment, denying it, trivialising it, defying it, all in fleeting temperamental fits that is supposed to excuse the excess and void his statements of their seriousness and meaning.

He perfected a quaintly flippant brand of politics inherently incapable of dealing with sensitive issues. So what his party said and did diverge. NC swore by Kashmiri sub-nationalism, its core constituency, but in public perception, it appeared always willing to compromise it for power. Autonomy, the party’s central plank became little more than a slogan, resurrected in times of urgent political or electoral necessity only.

But the cardinal sin of the NC was that it started looking at the politics more with regard to New Delhi than with reference to the people of Jammu and Kashmir. Keeping centre in good humour was seen as the stronger guarantee of perpetuation in power than being responsive to the people. There were reasons for this evidently bizarre approach: the NC’s history in power where it has been at the receiving end of New Delhi’s eagerness to control and guide the situation in Kashmir.

Result of this was a deep-seated paranoia in the party about the overarching and invisible role of New Delhi that is seen pivotal to who governs Jammu and Kashmir, relegating people to a secondary position. It is this insecurity about the democracy, this realization of its flawed operation in the erstwhile state that made NC perennially uncertain about its political future. And may explain in large part why Abdullah didn’t resign in 1999 and why Omar didn’t through 2010.

Future Uncertain

So far, mainstream politics in Kashmir has operated in a space between separatism and an outrightly pro-Indian stance. It has galvanized public support by making a case for New Delhi in Kashmir within the framework of Article 370 that guaranteed special rights to people and offered protection against demographic change. This space is gone now. Abdullah was its chief proponent. They can now only demand back this space, not operate in it.

Where do we go from here? No easy answers to this question. There are many imponderables in air: It will be a challenge for the political parties led by Abdullah to carry out their politics in the transformed political context? How will the government respond if this politics veers starkly from its expectations? The answers are still in future. Until then, the situation in Kashmir looks set to go on regardless: people silently simmering at the lingering denial of rights and the government largely impervious to their grievances.

Mehbooba Meets Farooq Abdullah, Sajjad Lone on August 2, 2019

In such a politically drained environment, Abdullah’s role becomes critical. Six-party alliance that he informally heads has become a sort of ‘Hurriyat of establishment politics’. Gupkar Declaration that seeks reversal of August 5, 2019 move has made the mainstream parties relevant to the situation provided they back the declaration up with a credible pursuit of the political goal. This is where Abdullah’s words and deeds assume their new significance. As his interview with Thapar shows, he has effortlessly slotted into this role. As for the future, we can only keep our fingers crossed.

from Kashmir Life https://ift.tt/3kPl9e2

via IFTTThttps://kashmirlife.net

No comments:

Post a Comment