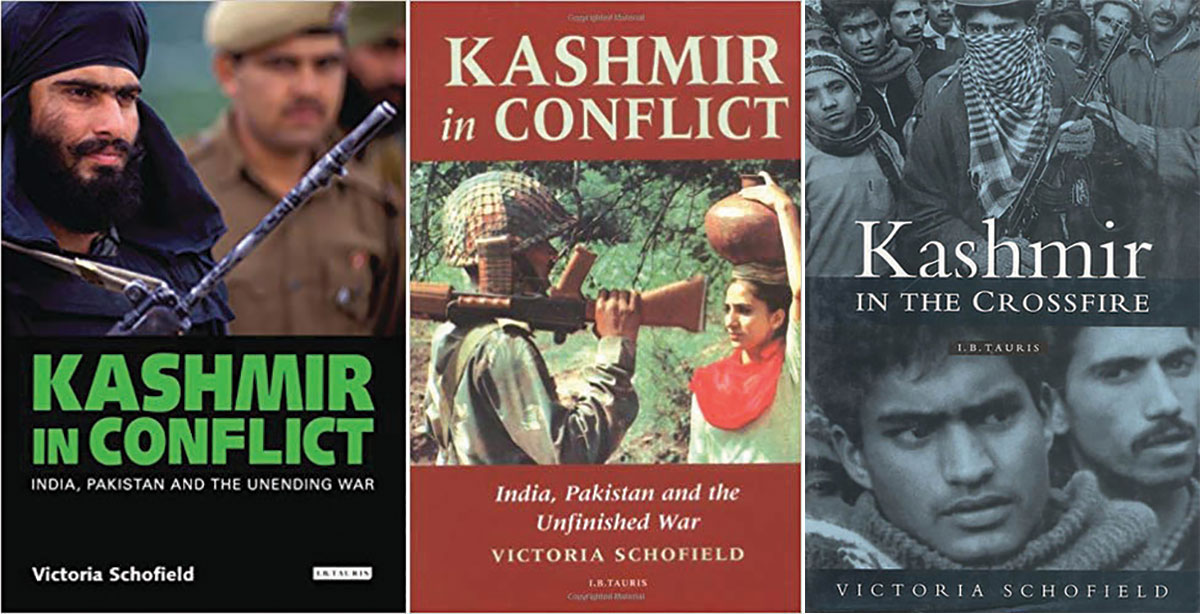

Rosemary Victoria Schofield is a British historian who authored Kashmir In The Crossfire in 1996. A classmate and friend of slain Pakistan premier Benazir Bhutto at the Oxford, her Kashmir book has seen four revised editions, so far. Right now, she is busy researching to add the happenings in the last decade to the book. In Srinagar, she spoke to Masood Hussain

Rosemary Victoria Schofield

KASHMIR LIFE (KL): Kashmir knows a concerned author and academic but not the real Victoria Schofield?

VICTORIA SCHOFIELD (VS): Victoria Schofield is a writer, a historian, a journalist who grew up in the United Kingdom, went to the University to study history where I met Benazir Bhutto. Then I went to live in Pakistan in 1978-79. Then, I came back to work with the BBC where I realised that I can never be a South Asia expert if I did not go to India.

While I was on the way to India, I met someone from Kashmir. I intended to do some interviews in Delhi but I came to Kashmir, instead. It was 1981 and this was the place where we are right now, where it all began. That is how my love of Kashmir began. Having seen the valley, its beauty, I became interested in the people, and, as a historian, I became interested in its politics.

KL: How was Kashmir 1981?

VS: It was peaceful and beautiful. That is what struck me, its beauty. There was also this feeling, even then, the feeling of overriding unresolved situation. At that time, you could not tell, and I had no knowledge to tell that it will flare up and become what it is now. I was much younger than I am now, and I lacked the knowledge, the understanding, and the historical awareness that I now have, after studying the issue in depth.

KL: You met Sheikh Abdullah?

VS: He was still alive but I never met him. I have met Dr Farooq Abdullah and Omar Abdullah. I have met many political leaders during that period and later.

KL: Was it that particular visit that led you to believe that Kashmir needs to be written about or was the situation that emerged later that encouraged you to do what you did?

VS: I think it was the latter politics that took place that reshaped my priorities. I have been going to Pakistan and by that time Benazir Bhutto became Prime Minister. The insurgency really began in 1989. It was because of that period, having had the visual image of Kashmir, that is when I decided to write about Jammu and Kashmir because it seemed to be a very unwritten subject.

I would pick up a book in Pakistan, written by a Pakistani. And then I will pick up an Indian book in India, written by an Indian. What could I gather was that as if it (Kashmir) was a piece of real estate. There was not any understanding that it was a piece of territory in which people lived. I did not find any literature especially by a foreigner which brought up the voices of Kashmiris.

If you look at the first book Kashmir In The Crossfire, I am making a big point about saying that I have tried to talking to Kashmiris to find their stories, their truth. During that research phase, I did travel widely – I visited the Pakistani side of Kashmir, Gilgit Baltistan, Kashmir Valley, Ladakh, Kargil and Jammu, to try and understand the complexities of this state which the British put together as a creation in 1846.

KL: How important is Kashmir to the politics of India and Pakistan?

VS: They always talk about it. It is obviously the most important. Pakistan would say it is the core issue. If you think back to 1947, had there not been a Kashmir issue, so to speak, see the different countries the India and Pakistan would have been. It is highly unlikely that there would have been these nationalistic borders, to be crossed at one point at Wagha. There would have been a greater co-existence; if they did not have the Kashmir issue to fight each other. And they have been consistently fighting, whether it is physically at war or a war on paper about the status of Jammu and Kashmir.

KL: Kashmir 1990 triggered a lot of interest by the academics as a result of which a lot of books were authored. Three decades later, it seems Kashmir is off the academic priority. Is it true?

VS: I think the problem with the issue is, as far as I have covered, is that nobody can quite see where the end is. And you can get very concerned about an issue; you can promote an issue, and work on it. But if you do not know, where you are leading, people turn their attention to something else. I think that is one of the problems.

Yes, it (Kashmir) would suddenly flash into headlines if it was a terrorist attack, or if there is a likelihood of war, anything like that. But once you are looking actually on the resolution, it is complicated. You have to have this in-depth knowledge to understand it not a quick fix situation.

Add to that, as you well know, there have been various attempts at talks in 1962 and 1963 brokered by the UK and the USA. Since the Shimla agreement in 1972, the government of India has a central tenant of its Kashmir policy that it is a bilateral issue with Pakistan. So you can not break the deadlock and have to injection of different oxygen into an issue that is really stuck in the rhetoric. You cannot have an option of a mediator, you can permit a facilitator.

We in Britain, we had a longstanding problem with Northern Ireland. We realised we had a problem and we brought in the United States. It broke the deadlock, changed the dynamic.

When you got the difficulty, the governments do face, they seek help. But some governments do not seek help and no country can force itself upon. You have to be invited in to be a facilitator or a mediator. This is one of the biggest difficulty in understanding the Kashmir pessimism. But it is very difficult to know what the next step is going to be.

KL: You entire academic exercise completed when India was ruled by Congress. Now it is ruled by a rightwing party. What is the difference between the two as for as Kashmir is concerned?

VS: I think I have seen a marked difference in terms of the governments particularly during the insurgency in the nineties; you had a feeling that these Kashmiris were misguided youth, asking for something, they were separatists; they could be brought back into the fold. Now, in this latest rhetoric, Kashmiris are the other. I think, one of the watersheds was in the aftermath of Pulwama attack when Kashmiris were asked to go home. You do not do that with the people, you think, they are your own citizens. That was the marked difference.

In addition, the use of pellet guns, which was supposed to be meant the most humane, non-lethal weapon after tear gas and water guns did not work, eventually proved not a non-lethal weapon. When it blinds over a thousand people so that I find it very peculiar that its use has not been immediately curtailed. So there is a change. Even in terms of attitudinal approach, I do not feel it is being for the better.

KL: There is a serious effort aimed at integrating Kashmir. Will it impact the psyche of Kashmir and the issue of Kashmir?

VS: As far as I know, Kashmiris have jealously guarded Article 370 and Article 35A, which enshrines the hereditary state order regarding permanent residents. So I think, the average Kashmiris are not going to welcome it.

It will impact the issue of Kashmir because it will be a step in the direction which the Indian government may think it wants in terms of integration. But it will, I will say, undoubtedly fly in the face of what the average Kashmiri wants and thinks (about) what they accepted when the state became part of India in 1947 with its special status.

KL: Will Delhi’s Kashmir approach on special status override the bilateralism between India and Pakistan?

VS: That is an issue between India and Pakistan. While Article 370 will impact the Valley of Kashmir, Jammu and Ladakh but let us not forget that one-third of the state, as Indians would say, is under the occupation of Pakistan. So they still have to sit down on the negotiations table and talk to Pakistan about the status of Gilgit and Baltistan and PoK /AJK.

KL: There were some CBM on Kashmir between India and Pakistan and one of them was a window on the LoC for a barter trade between the two parts of Jammu and Kashmir. It stands closed now. Does this closure take Kashmir far away from any reconciliation?

VS: I would like to think, this is temporary. I think one can go back to what was already achieved. You had done this in 2005 and it had benefitted the inhabitants of both parts of the state. So I would like to think, when everything settles down, one could revert to cross border trade.

KL: When you wrote the book on Kashmir, the Valley lacked its own voices. Now we have many boys and girls writing their stories?

VS: I think that is a very positive development. Since I started writing, I will say, many people in the world are much more concerned about the inhabitants of the Jammu and Kashmir state. They are no more regarded, as I earlier said, a piece of the real estate. But I am thrilled that many Kashmiris, starting with Basharat Pir, are written novels, poetry, and fact books. I am constantly contacted by the young Kashmiris who are studying in the UK and USA, working on their PhD or something that they seek help on some aspect of Kashmir. That is very important. I think it is important for Kashmiris to know their own history.

from Kashmir Life http://bit.ly/2KbJv2x

via IFTTThttps://kashmirlife.net

No comments:

Post a Comment