A decade after Amir-e-Kabir’s departure, his son came with 300 preachers. But his nearly two-decade-long sojourn in Srinagar witnessed a chain of events, still being debated by history. Prior to his departure, however, he bestowed the leadership of Islam upon Sheikh Nooruddin Wali, reports Masood Hussain

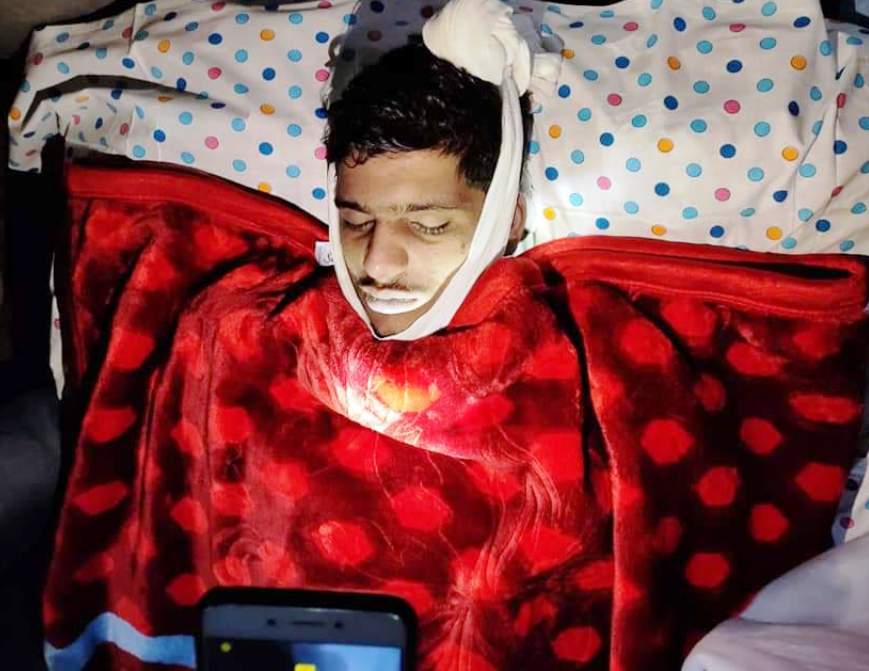

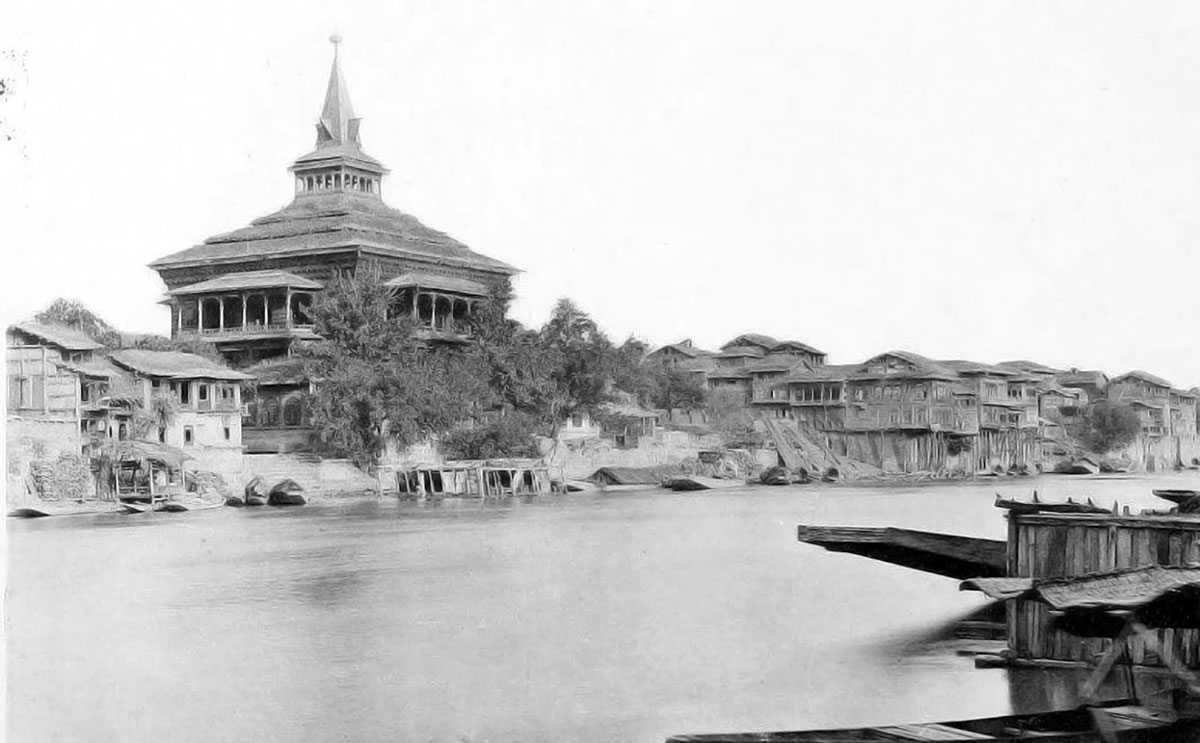

An 1890 photograph of Khanqah and its adjoining homes taken from the banks of Jhelum.

The Islam preceded the Central Asian preachers in Kashmir. But it was peculiar – the monotheism was rooted in the local Hindu traditions.

Even after the Sayyids’ came and initiated a long time relationship with the ruling elite, also Muslims, nothing much changed. They corrected the robes of some rulers but could not go beyond a point. Rulers opened schools for teaching the Quran, funded hospices but did not take the orthodox preachers seriously in statecraft because their subjects, advisers and the bureaucracy was Hindu. Kings would marry Hindu women as it was an established medieval norm of staying connected with the majority. They believed in witchcraft and routinely performed homa ceremonies over new births, with only one correction, a pir would replace a Brahmin priest. Qutubuddin had a son in old age and he saw it as the blessing of a Hindu yogi.

This was as truer with Sultan Shihabuddin (1354-73) as it was with Sultan Qutubuddin (1373-89), the two kings with whom the Amir-e-Kabir had direct access to. Both held Shah-e-Hamadan high with respect.

The Amir left Kashmir and died in 1383. Six years after his departure, Qutubuddin also died. For almost a decade, no major Sayyid came to Kashmir. But those who had accompanied the Amir had grown quite an impressive lot.

Sikander, Qutubuddin’s minor orphan, had to wait for many years till he grew up and understood the job. By then, he had lost his younger brother, Haibat, to the palace intrigue. His mother, Queen Sura who actually succeeded her husband and operated as a Reagent for many years had ordered the execution of her daughter and son-in-law, to protect Sikander’s rightful inheritance, the throne. Finally, when Sikander took over, he avenged the killing of his brother and fought some small battles to keep the kingdom in order.

The Son Arrives

In 1393, Mir Muhammad Hamadani came to Srinagar. He is reported to have led a batch of 300 Sayyids to Kashmir. “His arrival and subsequent interest in the development of Islam can really be considered a turning point in the history of Islam,” Darakhshan Abdullah writes in Religious Policy of Sultans. “His teachings have had far-reaching consequences on Sultan Sikandar and the Kashmiri society as well.”

When a young Sultan Sikander received him warmly in Srinagar, Mir was 22. Sayyid Ali, the Tarikh-e-Kashmir author, perhaps the only major source of information about the arrival of the Central Asian preachers, commented: “He purified the hearts and minds of people and removed traces of infidelity from them.”

Mohibul Hassan insists Sikandar was able, brave, generous, and a caring ruler who rolled back “oppressive taxes” and established schools and hospitals. He “abstained from wine and other intoxicants” and “on religious grounds he did not listen to music”; banned “all the gay celebrations” and “never indulged in extra-marital relations”. He had taken Mira, daughter of Ohind ruler, as his wife and later married Sobha Devi. Mira was a mother to his three sons and Devi to two sons and two daughters.

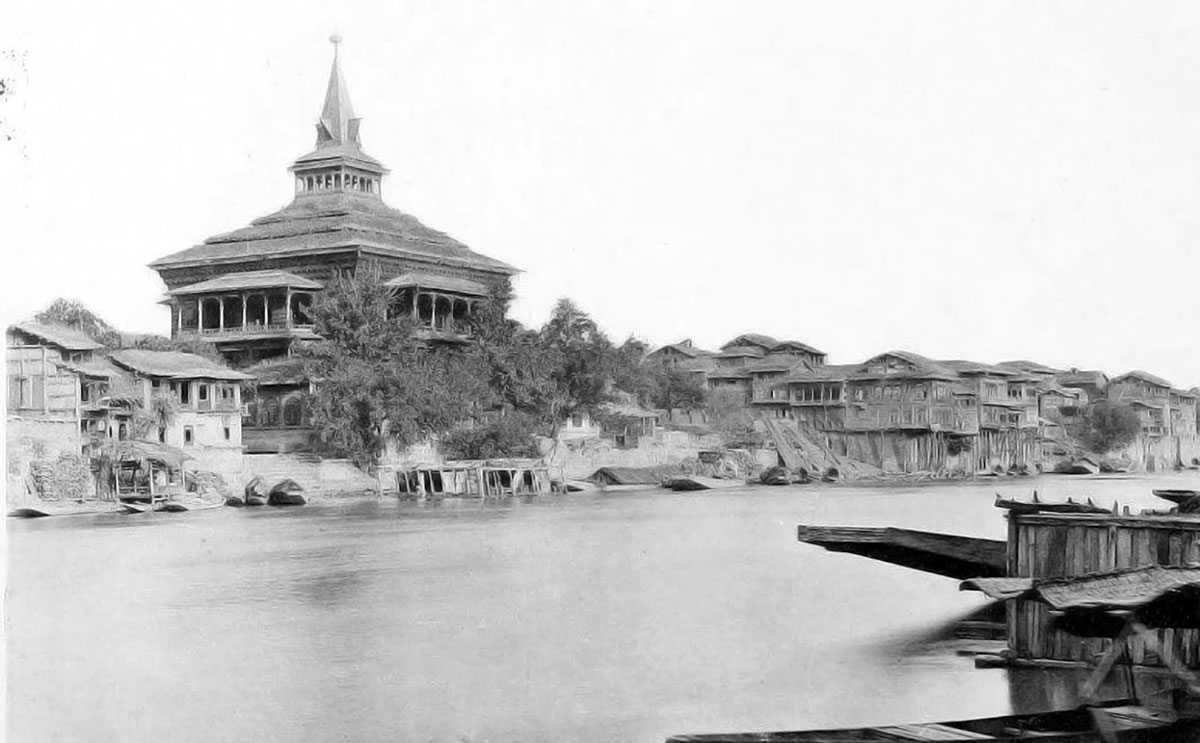

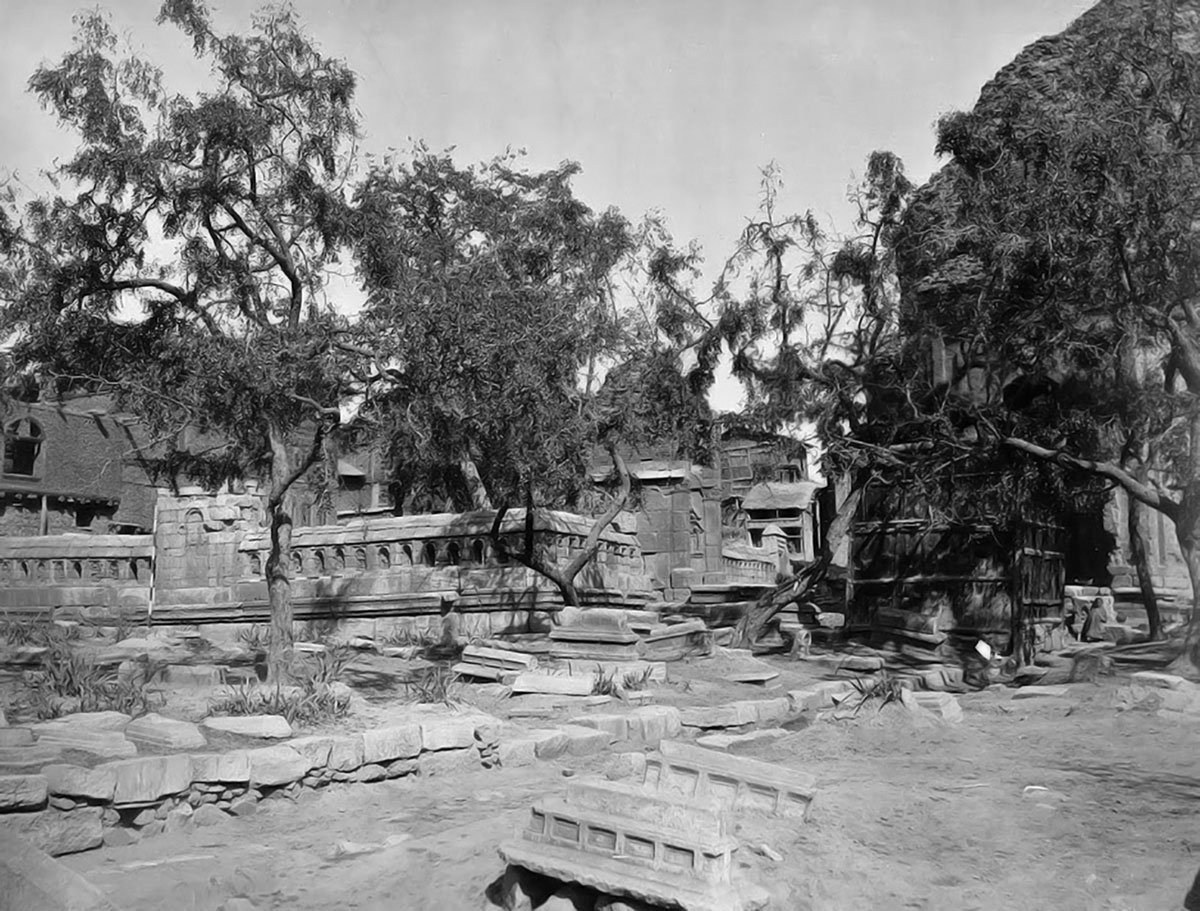

An 1868 photograph of Martan temple in Mattan outskirts.

“Sikandar was a great patron of learned men and Sufis, and during his reign, many of them came to Kashmir from Persia and Central Asia,” Hassan has recorded in Kashmir Under The Sultans, a major work on Kashmir Sultanate. “The Sultan treated them with respect, and gave them jagirs which could be inherited by their descendants.” Those who entered Kashmir in his reign included former Qazi of Shiraz, Sayyid Hasan; Isfahan author, Sayyid Ahmad; Khwarizm poet Sayyid Muhammad; Bukhara saint, Syed Jalaluddin, who came along with his followers, Baba Haji Adham, and Baba Hasan. Given their expertise, some of them were given jobs – the Qazi from Shiraz became Qazi of Kashmir. Sayyid Hussain Khwarazmi was appointed tutor to the two princes including Zainulabidin.

The arrival of Amir’s son was a game-changer. Quickly, the Sultan ordered the construction of a Khanqah, at the same place where the Suffa was created for the Amir, a decade back. The first Waqf was created in Kashmir’s history as the king allotted the village of Wachi, Tral and Mattan to the Khanqah where a lunghar (community kitchen) would operate and poor would be taken care of.

The Khanqah was located near Kali Mandir. This has a written document detailing the possession. “The endowment deed of this Khanqah, dated 11 January 1399, and signed and sealed by Sayyid Muhammad Hamadani, the son and successor of Sayyid Ali Hamadani, is a document of great historical significance,” Dr R K Parmu wrote in A History of Muslim Rule in Kashmir (1320-1819). “It shows the earliest limits of the Khanqah, the purpose of its foundation, and the means of its maintenance. It is the earliest available document showing the origin of the institution of Awqaf in the Muslim ecclesiastical system in Kashmir.”

The emerging situation had angered the court historian, Jonaraja, who explained the immigration of Muslims into Kashmir like “locusts enter a good field of corn”. Entries in his Rajatarangni suggest his extreme unhappiness over the association between the king and the preacher.

“It was perhaps owing to the sins of the subjects that the king had a fondness for Yavanas, even as a boy has a fondness for mud. Many Yavanas left other sovereigns and took shelter under the king who was renowned for charity, even as bees leave the flowers and settle on elephants.” Yavanas and Mleechhas are the various names that Kashmir’s Hindu historians have used to mention Muslims.

An undated photograph of Kashmiri singers performing in a private function.

The routine of the king changed. Recorded Jonaraja: “The King waited on him daily as humble as a servant, and like a student, he daily took his lessons from him. He placed Mahammada before him and was attentive to him like a slave. As the wind destroys the trees and the locusts the Shali crop, so did the yavanas destroy the usages of Kashmira. Attracted by the gifts and honours which the king bestowed, and by his kindness, the mleechhas entered Kashmira, even as locusts enter a good field of corn.”

Hamdani Jr is recorded to have gifted the king a Badakshan ruby – after the Khanqah construction and authored Risala-i-Sikandari, a book about Sufism, for the king.

Key Conversion

Of the few people who were Sikander’s most confidants’ was Suha Bhatta, literally his army chief and the Chief Minister. In association with Mir Hamadani, he converted to Islam and took the name Malik Saifuddin. Soon after his conversion to Islam, when Mir Hamadani’s wife, Bibi Taj Khatoon (daughter of Sayyid Husain Baihaqi) died, Malik gave him his daughter Subiya Razia in marriage. This cemented a new relationship between the king’s mentor and spiritual guide and his army chief. Suha’s interventions have remained the key criticism of Sikander so far.

Situation shifted in Kashmir quite soon. Sikander announced the implementation of Sharia in the kingdom. “He banned the use of wine and other intoxicants, and prohibited gambling, the dancing of women and the playing of musical instruments like the flute, lute, guitar, allowing only the playing of drum and fife for military purposes,” details Muhibul Hassan, insisting these measures were adopted by Sikandar under the influence of Sayyid Muhammad Hamadani. “It was also due to his advice that the Sultan imposed two pals of silver as Jaziya upon the non-Muslims, and prohibited Sati and the application of qashqa (tilak).” Hassan sees Suha Bhatta as Sikander’s “evil genius”.

Terming the conversion as Hamadani’s “most significant achievement”, Darakhshan insists that by then converts to Islam were coming from low castes. “This singular conversion provided a new base to the process of proselytisation – to win over more and more high caste Hindus, Suha Bhatta applied the force of motivation and necessary persecution.”

“The king forgot his kingly duties and took delight day and night in breaking images. The good fortune of the people left them – there was no city, no town, no village, no wood, where Suha, the Turshika left the temples of gods unbroken,” Jonaraja recorded in his memoir about Kashmira. “Of the images which once had existed, the name alone was left.”

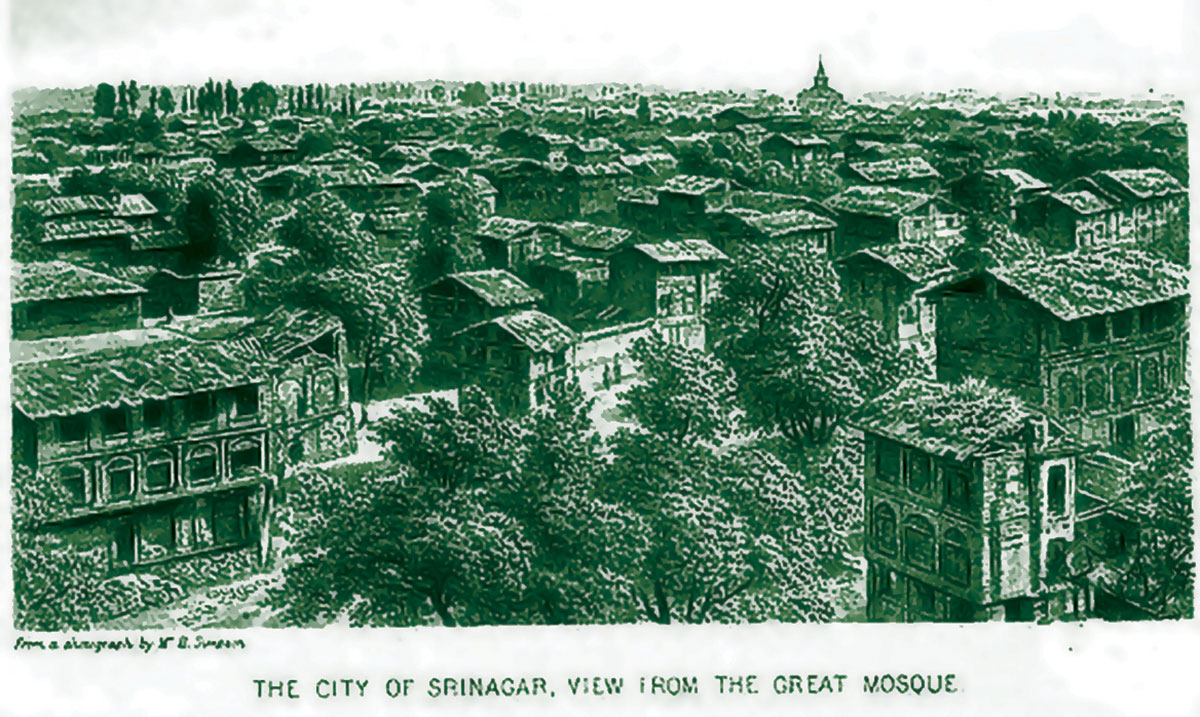

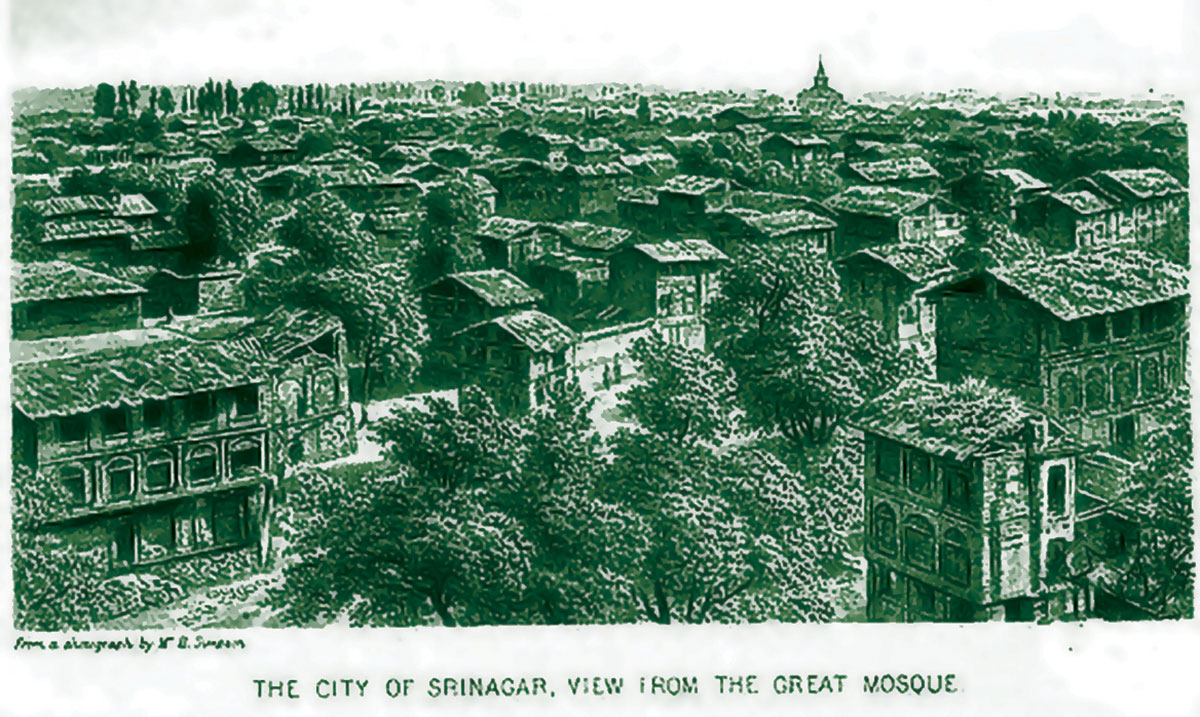

An image of an organised Srinagar city. This Srinagar was visible from the Jamia Masjid.

Tarikah-i-Kashmir also mentions various instances including that of the demolition of a “huge temple” in Sikanderpora to pave way for setting up of Jamia Masjid. “In fact, in every village and town, where a temple existed it was demolished, at the behest of Sayyid Muhammad Hamadani and a mosque built in its place,” Sayyid Ali writes in his history that was rendered into English by noted historian Dr Abdul Qayum Rafiqi. “Thus, Kashmir became like a paradise.”

Most of the historians, however, see Sikander’s so-called iconoclasm as an outcome of his ‘turn court’ deputy’s personal war against his community. Jonaraja has recorded at length about demolitions, insisting that after demolishing the temples, Suha “felt the satisfaction which one feels on recovering from illness”. Historians, however, see the accounts of temple destruction exaggerated because the rulers who succeeded Sikander did find major temples intact. Interestingly enough, Shoba Devi, his queen, constructed a Shiva temple with a golden linga. How could a bout-shikan permit it?

Sikander was like his predecessors, initially. Liberal Sultan had three key aides – Suha Bhat, Udaka and Shankra, all Hindus. The change came only after Suha Bhat converted and Mir Muhammad Hamadani started advising on state affairs.

Over the centuries, Kashmir society has evolved many legends to explain Suhabhatta’s behaviour. One day, a legend says, Bhatta fell ill and was taken to a Khurasani Hakim who prescribed him mutton soup. The vegetarian Brahmin sought permission from his community and was granted. Later, however, his community said Bhatta was polluted and the family became impure. His daughter did not get a match in the Hindu community, the legend suggests. She later married Mir Muhammad Hamadani and died within a year of the nikkah.

The Builder Rises

While his deputy was busy managing the new converts to the new faith, the king started building the physical infrastructure for it. After establishing the Sikanderpora, he laid the foundation stone for the Khanqah, the first one in Srinagar. In 1398, he started constructing the Jamia Masjid Srinagar which, R C Kak, the author of Ancient Monuments in Kashmir, insists was completed in 1402. Interestingly, it was one of the followers of Mir Syed Ali Hamadani, Sadruddin Khurasani who gave the architectural lay-out for the grand mosque of Kashmir.

Insisting that there was no parallel to the Jamia Masjid in the world at that point in time, Sayyid Ali, the historian, has offered some basic information about the construction. “One of the architects of the mosque was Khawaja Sadruddin who hailed from Khurasan and had come (to Kashmir) with Sayyid Muhammad Hamadani,” the Tarikh-i-Kashmir has recorded. “He was accomplished in the art of construction. Another architect, Sayyid Muhammad Loristani, who had (also) perfected the art of construction, completed this grand construction in three years, together with the local artisans. It was completed in 804/1401.”

Mohibul Hassan lists a number of other constructions in Kashmir that were crucial to the king’s faith: a mosque each in Bijbehara, spring of Bavan; Khanqah’s at Vachi, Tral, Sopore; besides, laying the foundation for the Idgah in Srinagar. Some of the projects were completed by his son, Ali Shah, one of the weakest Sultans.

Rising Reactions

With the spread of Islam and the rising infrastructure for the new faith, another development was almost simultaneous: the reaction to the abusing of authority in matters of faith. The Rishis’, operating mostly outside Srinagar, were unhappy with it. Interestingly, however, Sheikh Noorudin Noorani has sung in Sikander’s praise.

But the differences started within the ulema circuit closer to the dubar. Sayyid Ali’s Tarikh-i-Kashmir, the oldest book detailing the arrival of Sayyids, mentions a mystic named Sayyid Mohammad Hissari. A resident of Hisar, possibly in Punjab, he had come to Kashmir during Sikander’s reign, slightly ahead of Sayyid Muhammad Hamadani’s arrival. The king, according to Tarikh-i-Kashmir had constructed a house for the mystic near his palace and would routinely visit him. However, after the Hamadani’s arrival, the king became his literal disciple. This could have been a personal conflict between the two learned men. Sayyid Ali has given a lot of detail of this tension.

Rafiqi, in the introduction to Sayyid Ali’s history, which he rendered into English, has insisted that the two great godly men would not have a strained relationship for personal reasons but could differ only on ideological issues.

“Saiyid Hisari told the Sultan that he was (now) frequently visiting a young lad, who was a less educated person, whereas he very seldom visited a grey-bearded man like him,” Tarikh-i-Kashmir has recorded, insisting Hamadani turned very sad when he heard it. Then in the sleep, his father appeared and told him: “I had advised you that you must first acquire scholastic knowledge and then alone embark upon the journey. Since you did not complete your education (before undertaking the travels) that is why you had to face this type of situation.”

The two men reconciled their differences. But Mir Muhammad Hamadani had decided to proceed on Haj. After more than 18 years, he left Kashmir. He performed Haj and returned to Khatlan where he died and was laid to rest near the grave of the Amir.

Policy Shift

After Hamadani departure, the so-called iconoclast reshaped his policy. Insists Jonaraja: “Though the King Shri Shikandhara was often instigated by Suha to persecute the twice-born, he, whose purpose was tempered by kindness, fixed with some difficulty, a limit to the advance of the great sea of the Yavana.”

Various historians have mentioned that the Sultan repaired some of the temples. In a twentieth-century discovery, a sculpture was found at Ganesh Mandir in Srinagar that bears a “dedicatory description” to Sultan Sikandar in Sharda script. Though the contemporary Kashmir is separated from Medieval Kashmir by more than 600 years, the temple demolitions, if any, are still being used and abused to prove a narrative.

Nund Reshi Takes Over

The Tarikh-e-Kashmir author was fully aware of the existence of a strong Rishi movement. Seemingly, he was highly impressed by Sheikh Nooroudin Noorani and his team of Rishis and has gone to an extent in highlighting their spiritual powers. He was also privy to a series of interactions between Mir Muhammad Hamadani and the Sheikh and has referred to various investigations that the former did in understanding the latter.

However, he has not given many details about the landmark meeting that the two exalted Muslims had at Zalsu, near Chrar-e-Sharief on Rajab 15, 814 AH (November 1411). It is the same village where Sheikh had started a centre for the education of women.

Unlike Sayyid Ali, details of the event have not been missed by history. In fact, Sheikh has personally recorded it in his verses.

“It is significant that his decision to pay a personal visit to the Rishi was not liked by some of his Sayyid followers mainly due to two reasons,” writes Prof M Ishaq Khan in his magnum opus Kashmir’s Transition To Islam. “First, as already stated, the asceticism of Nuruddin was repugnant to their Shari’a -oriented lifestyle, and second, contrary to the Sunna the Sayyids were highly conscious of their pedigrees.”

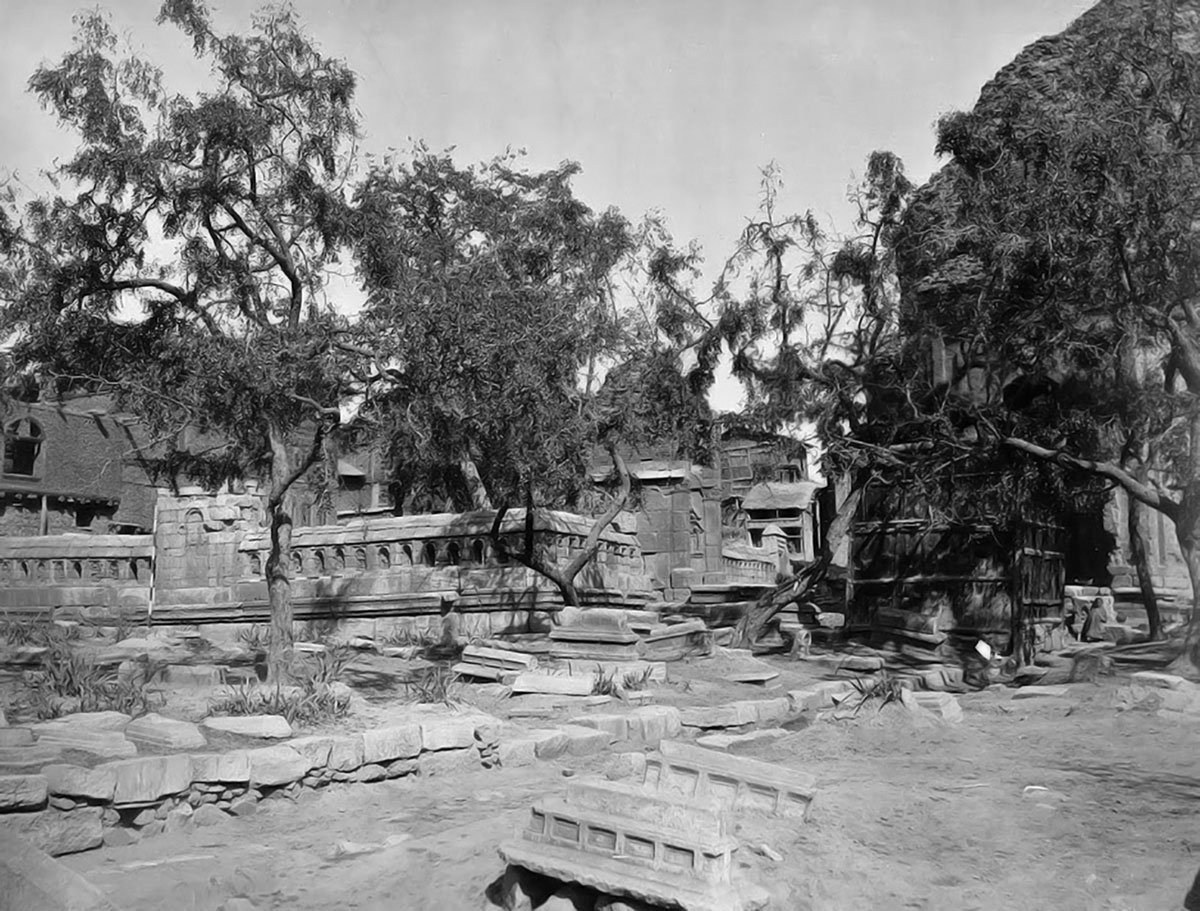

An 1886 photograph of the Mazar-e-Salateen where popular Sultan Zainulabidin is buried.

But when the leader decided to go to Zalsu, everybody followed. In fact, Sheikh-ul-Aalam came out to greet and receive them. There, in the meeting the discussions took place. Interestingly, two exalted women disciples of Sheikh attended the meeting and participated in the discussions. At the end of it, Khat-e-Irshad was issued in which Mir Muhammad Hamadani respected the institution of Rishis, permitted the Chila, a peculiar style of self purity through isolation, and accepted Sheikh as a Wali. The document is seen as the formal induction of Sheikh into the Kubrawi order following which he took over as the leader of the movement of Islam in Kashmir at a time when Muslims were in a minority. It was in this backdrop that, till recently, as even Khan mentioned, the devotees from Srinagar city would go to attend the yearly Urs of Sheikh under the leadership of the custodian of Khanqah-e-Moala.

Khat-e-Irshad was discussed by various historians but its rediscovery is recent. It is one of the various vital documents that are in possession of the Khanqah mujawirs and needs to be immediately protected and digitization. Besides, there are a series of royal decrees by Mughals and Afghans that are, according to insiders, on the verge of being lost. These documents have survived the 1995 fire in which Chrar-e-Sharief town was destroyed along with the shrine but may be lost to termites. Khat-e-Irshad is signed by the two exalted souls and carries a seal of Sultan Sikandar, the so-called iconoclast.

It is not clear, however, whether the meeting was the outcome of the efforts of the Sultan Sikander or Mir Muhammad Hamadani or both. But it was inevitable in wake of Hamadani’s decision to leave Kashmir. What is more important was that he avoided being succeeded by a Sayyid, perhaps knowing the difficulties in their style and the popularity of Sheikh almost everywhere excepting parts of Srinagar city, the centre of power.

Historians are divided over the date when Mir Muhammad Hamadani left Kashmir. Muhibul Hassan says Mir left after being in Kashmir for 12 years, which is incorrect. Khan says he left after spending 18 years in Kashmir, which is closer to reality because the year Khat-e-Irshad was issued, completed his 18 years of stay in Kashmir. But Sheikh specialists like Asadullah Afaaqi, in his Hayat-e-Sheikh-ul-Aalam, insist that after the Zalsu declaration, Mir Muhammad Hamadani supervised the overall activities for three years and left in 817 AH (1414), which means a year after Sultan Sikander’s death.

With this document, the leadership of Islam in Kashmir returned to the local residents, the Rishis. In a quick follow-up, they got support from the Alawis, Kubrawis and the Suhurwardis. Despite all this, Sheikh did not compromise with the ruling elite. The tensions between the Sultans and the Sheikh remained. Sultans’ continued supporting the exalted Sayyids, funding the shrines and the mosques, but Khat-e-Irshad de-controlled the process of spread of Islam. Even after taking control of the movement, it still took Muslims a lot of effort to improve their numbers. “In reality, it was not until the end of the fifteenth century that a majority of the inhabitants of the valley had embraced Islam,” concludes Muhibul Hassan.

(This is the second of the three-part series of the crucial 33 years of Islam in medieval Kashmir)

from Kashmir Life http://bit.ly/2MqIlCW

via

IFTTThttps://kashmirlife.net