Shawls woven in Kashmir were fashion statements on Paris streets early nineteenth century. But it took a long time for the buyers to understand that the Cashmere they are wearing is from Kashmir, a place that was deliberately pushed into perpetual slavery by the British. The movement initiated by Thomas Moore’s Lallarukh was follow up by the master weavers by clubbing the art with the history and cartography, writes M Saleem Beg insisting that there is no evidence suggesting the making of map Shawls of Srinagar was a royal project

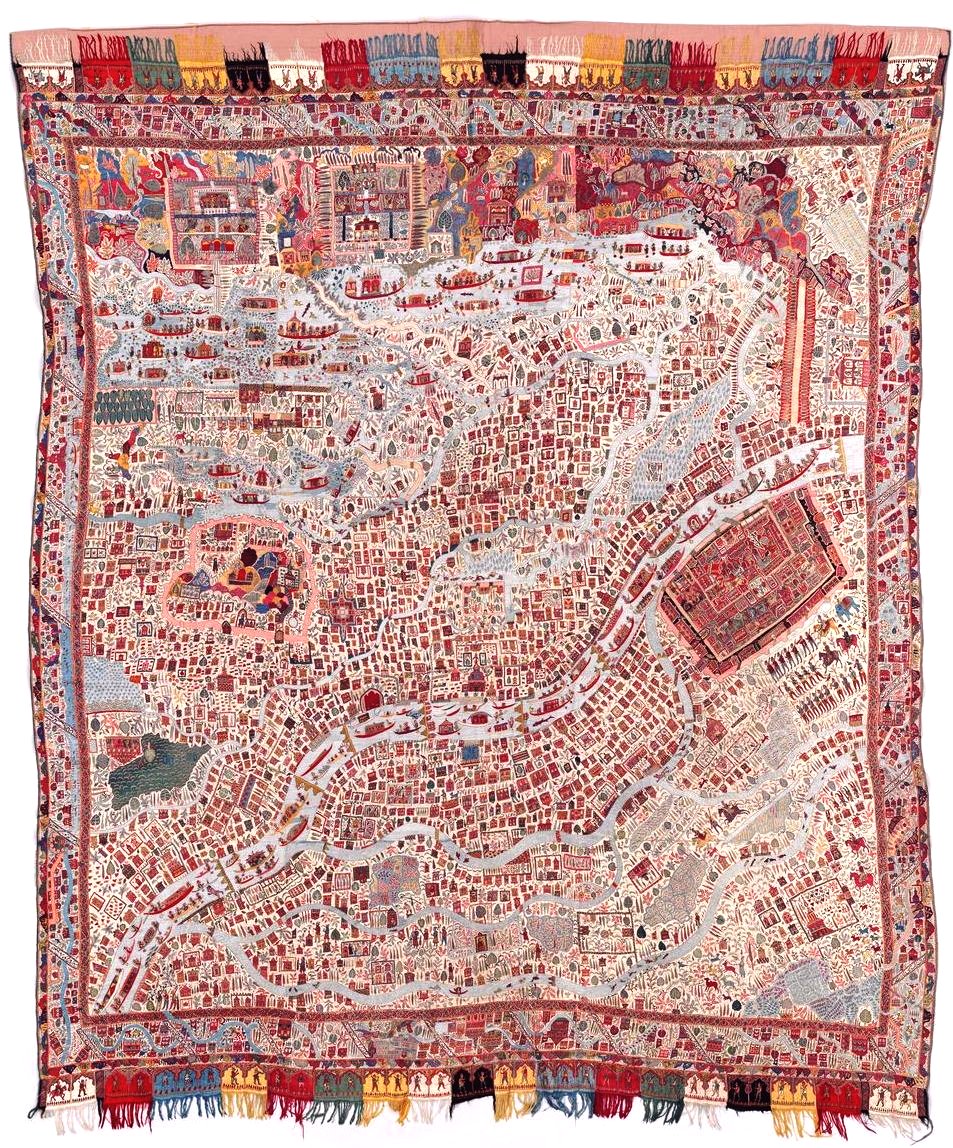

A map shawl of Srinagar preserved in the Victoria and Albert Museum London.

Kashmir shawl, the finest of the Indian crafts, begs no introduction. World over, it has been a fashion statement, a desire and a passion for its proud owners who would, through this prized possession, display their fashion consciousness, affluence and class.

It is on this broad and sweeping canvass that one finds mention of a map shawl from Kashmir. In the legend about the shawl, it is supposed to be one of a pair commissioned by the Dogra Maharaja Ranbir Singh for presenting to the Prince of Wales.

This author attempted tracking the journey of this shawl through the validated sources and now based on this tracking this legend falls apart. This shawl was not a present from the Maharaja though we still do not know how it came to be acquired by its owners in Britain. The shawl was exhibited at the British Indian section of the Paris Universal Exhibition of 1878 and subsequently found a home in the South Kensington Museum.

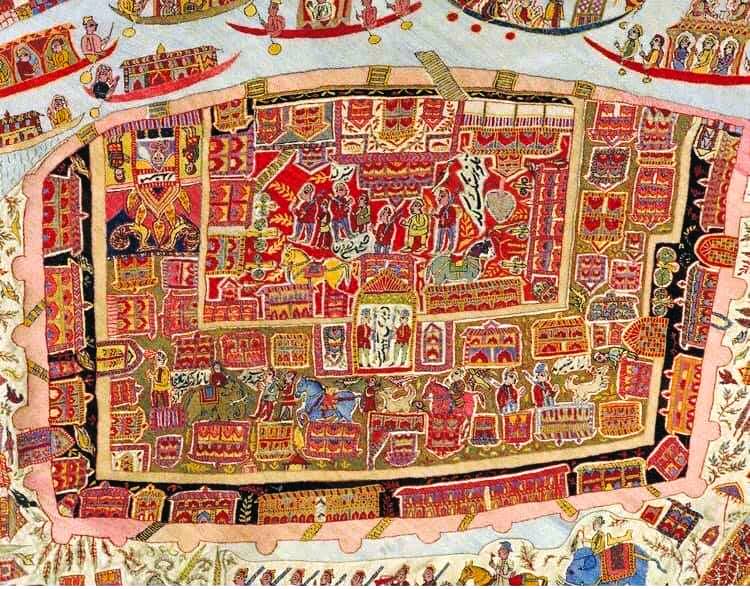

In this highly magnified stretch of the map shawl is seen the Shirghari Palace, the epicentre of Kashmir’s misrule.

The museum records have a description of the shawl, both interesting and revealing: “Never intended to be worn, this 19th-century embroidery depicts the city of Srinagar in Kashmir. Lake Dal and the river Jhelum are visible, as are the main mosque, fort and much smaller buildings. Maharaja Ranbir Singh of Jammu and Kashmir, who may be the haloed figure in a boat (upper left), probably commissioned the shawl.

Map shawl

Pashmina (goat-hair) embroidered with pashmina

Srinagar, Jammu and Kashmir, about 1870

Gift of Mrs Estelle Fuller through the Art Fund

V&A: IS.31-1970 [03/10/2015-10/01/2016]”

It also states that the producer/manufacturers name is unknown. Therefore the craftsman whose creation became one of the most cherished possessions in the world of historic textiles remains unknown and in oblivion. The description has no mention of the shawl having been presented to the British Royalty. The acquisition is credited to the lady, wife of an art collector.

George Christopher Molesworth Birdwood

George Birdwood, a colonial official and prolific commentator on the arts and crafts of India, compared the shawl to ‘the quaint drawing of a medieval picture… a photograph’ (1880).The comments of another observer from the early twentieth century indicate the importance of literary representations and tourism to descriptions of this shawl: “The Jhelum river running through the city, the Dal Lake, and all the celebrated baghs and gardens described in “Lalla Rookh” and so well known to the modern tourist” (Barker 1932). (Chishti: Producing Desire)

History On Shawls

Going back just two decades before the Shawl came to light, Kashmir, as geography was presumably not well known even while it was visited by European adventurers and missionaries for whom it was located in the distant and desolate extremes of Himalayas. This is corroborated from a reference in 1868 AD by one Arthur Brinckman, an Anglican missionary active in late-nineteenth-century Kashmir, again instructive; ‘I would like to inform the British public…of facts…of which it seems to be ignorant…that there really is a beautiful country, called Cashmere, situated in Asia; and that Cashmere is not a mere name distinguishing a peculiar kind of shawl’(Chishti: Producing Desire).

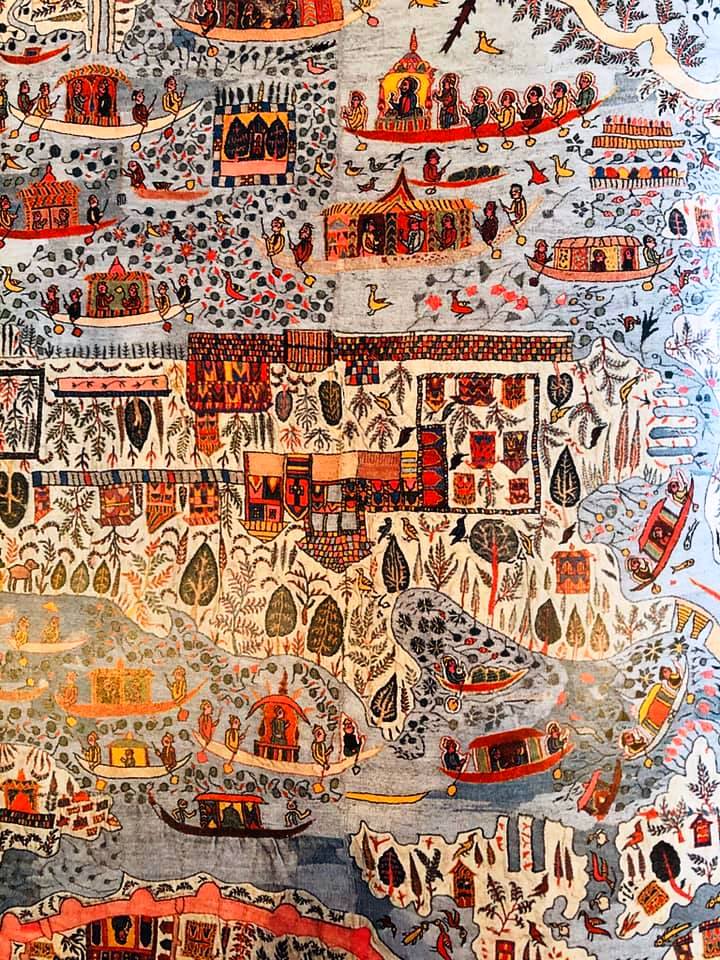

It needs a lot of magnification of the stretches of the Srinagar map shawl that the actual details and skill of the artisans are visible.

Attempting to draw the attention of his compatriots to ‘Cashmere’, a place on the very furthest reaches of the British Empire, Arthur Brinckman could not possibly have chosen a more evocative signifier than the shawl. Determined to expose Dogra misrule and the complicity of the colonial government, Brinckman, continued: ‘Because Tom Moore wrote a poem and mentions Cashmere in it, are we to think its existence only a myth? Ladies all know of it by its shawls, shopkeepers call their fine flannels by its name, yet we quietly shut our eyes to all the ruin we ourselves allow to exist there’ (1868, 12).

Thomas Moore

Chastising his readers for their purported ignorance, Brinckman knowingly gestured towards their keen awareness of Kashmir, ensured in no small measure by Thomas Moore’s famous poem, Lalla Rookh. As the quote indicates, shawls played a pivotal role in mediating this awareness. The easy conflation of ‘Cashmere’ the place with the eponymous garment, found so often in nineteenth-century European accounts, points not only to the webs of signification that linked their desirability but also to the fact that Kashmir – the place – was thought through the shawl. (Chishti: producing desire) It is, therefore, a bit of a surprise that we think of the shawl having represented our identity through ages when the shawl was known in the West independent of its place of origin.

As a backgrounder to the Map shawl that forms part of the famous product of desire, it would be in order to locate the shawl in its historic context. The word “shawl” originally referred not so much to a garment as to fabric, and the long shoulder mantle – in India originally worn by men – was only one of many varieties of shawl-goods. Shoulder mantles were woven in pairs, and often stitched together back-to-back; they were called do-shala. Square items, qasaba or rumal, were made for women’s wear, and long narrow ones, patka or shamla, for men’s sashes. Lengths of shawl fabric in all-over designs, jamawar, were intended to be tailored into men’s coats (jama).

Apart from these four main categories, about twenty-five varieties of shawl-goods were produced, including turbans, stockings, horses’ and elephants’ saddlecloths, carpets, curtains and other kinds of hangings, bedspreads, and shrouds for tombs.

Rees Encyclopedia, a well-respected encyclopaedia thus defines the shawl in the following terms: ‘Kashmir Shawls of the myriad varieties of textiles for which India was famous over much of Europe and Asia from at least the time of the Roman Empire, the Kashmir shawl stands out as the in the woollen textiles’.

That, soft and warm shawls were made in Kashmir or also in Kashmir is corroborated by a poetic reference from the great 11th-century grammarian and poet, Bilhana who travelled to mainland India for better opportunities and for seeking recognition and appreciation of his knowledge and scholarship. In a famous poem, reminiscing about his country of birth, Kashmir, at his romantic best, he laments:

‘where in the cold season the beauty of the breasts of women in warm with a delicate anointing of Saffron

Those ranku deer wool blankets give off a fragrance of musk’.

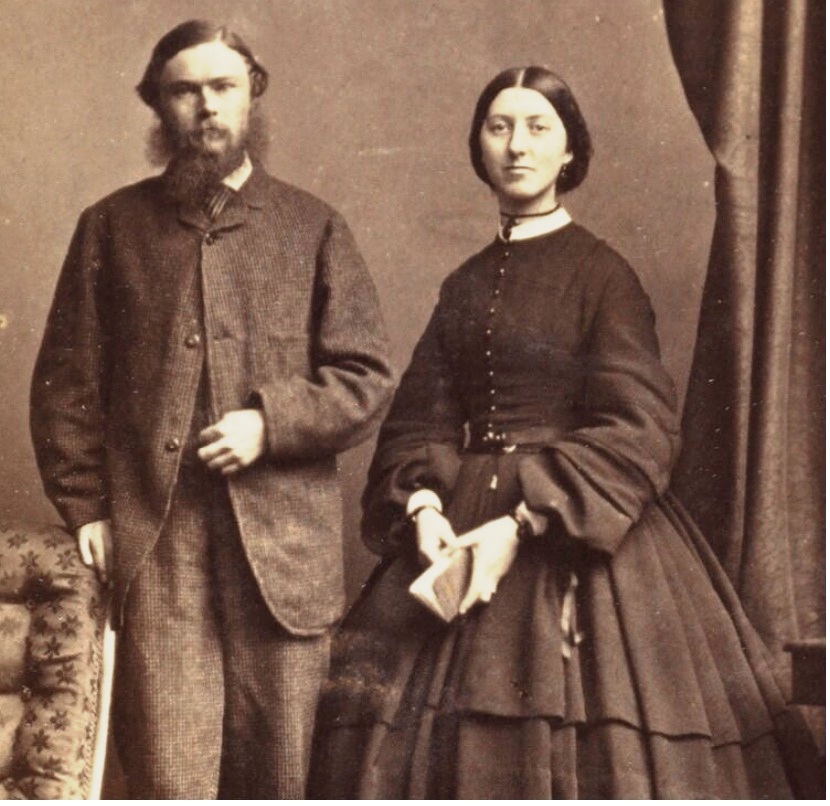

Christain missionaries Louisa Brinckman (née Swinny); and Arthur Brinckman in an 1864 photograph by an unnamed photographer. The portrait is part of the collections at the National Portrait Gallery London.

The reference to ranku deer is shatoosh or pashmina goat. Although its precise origin is lost in a haze of myth and legend, it is safe to say that it grew out of a unique combination: a superlatively fine fibre plus the highly developed set of skills necessary to work the fibre. Or, as a nineteenth-century government report put it, “It is impossible not to admire the felicitous conjunction, in the same region, of a natural product so valuable and of workmen so artistic.”

The raw material of the Kashmir shawl, known in the West as “cashmere,” is called pashm in India, and the fabric is woven from it pashmina. It is the warm soft undercoat grown by goats herded on the high-altitude plateaus of Tibet and Ladakh as protection against the bitter winter cold and combed out by herders at the onset of summer. For centuries the entire clip was sent down in a series of complex trading operations to Kashmir, the only place whose craftspeople had developed the skills necessary to process it.

The transformation of the raw pashm, a mass of greasy fibres, into a fabric renowned for its fineness involved a series of processes. The pashm dealer, locally called puye-woen, supplied the pashm in its raw state to women who, in the seclusion of their homes undertook the painstaking and laborious task of removing the coarse outer hairs from the fleece; they then cleaned and starched it with rice-flour paste combed and spun it on yender or charkha, similar to those used everywhere in rest of Indian subcontinent. The skill of spinning such delicate fibre was passed down over generations from mother to daughter.

In 1980s ‘Economist Intelligence Unit’ did a special publication on speciality fibres and Cashmere was one of the products that was obviously listed in this publication. In the write up it was stated that ‘while the world production of raw Cashmere fibre is 5,000 tones, Kashmir consumes just about 5 tons that are converted into shawls’. However, this fraction of the total produce is elevated to a finesse that imparted its geography and distinct name to the whole fibre. The fibre is processed in advanced industrial countries into ‘cashmere goods’ knitted or woven into lengths or garment piece goods. Interestingly while in Kashmir it has remained a hand-operated process from the conversion of raw pashm into shawls, in Europe M/S Dawson’s, a Scottish company for the first time invented the machine for mechanized de-hairing and combing of the raw pashm and then on spinning this into yarn of varying deniers.

Surprisingly the mechanized processing remained a family secret of Dawsons for more than 100 years after which Italians broke the secret code of processing and the industry touched newer heights making Italy as the main producers of Cashmere products like sweaters, mufflers, stoles and lengths.

File image of the artisan working on a shawl (KL Image: Bilal Bahadur)

In England, a large scale shawl industry with huge profits grew in a city, Paisley, where the mechanized version of Kashmir shawls was manufactured that over time became part of a counterfeit shawl trade throughout the western world. This is a subject that needs a separate and detailed treatment.

Coming back to the shawl, the classic Kashmir shawl employs a weave technically known as 2:2 twill tapestries, which is unique to this product. Tapestry implies that the design is woven into the very structure of the fabric; the weft is inserted not by a shuttle, but by a series of small bobbins, locally called tujis, filled with various coloured yarns. Depending on the complexity of the design, one line of the weft may involve scores of such insertions. In Kashmir the technique is known as kani, referring to different names for the bobbins. The design is based on a handwritten script for each design, the taalim, that caries instruction on the number of warp threads and the colour.

Maps Shawls

Drawing of maps has been a favoured pursuit for the artists who also doubled as cartographers. We know Kashmir has been a favourite subject of painters later on followed by photographers. The history of the maps reflects the fascination for drawing of maps for Kashmir with equal passion and enthusiasm. We know from the map history of the world that one of the oldest extant maps was drawn by Bernier in 17th Century. He had prepared it from his journey to Kashmir accompanying Mughal King Aurangzeb and then got it published in his travelogue. There is also a textile map of Kashmir in Jaipur Museum whose preparation is credited to the Rajput commanders who frequented Kashmir during the Mughal rule commencing from the great Mughal, Akbar (1556-1605).

Since the time of Zain-ul-Abidin who died in 1470, Kashmir was known for its woven and embroidered shawls. Several of them are in the form of maps of Srinagar, but no reference to their manufacture has been found in the literature. The map shawl in the SPS Museum at Srinagar is said to have been made for Maharaja Ranjit Singh of Punjab by Ama Kulu in the karkhana of Mohiuddin at Maharaj Ganj, Srinagar. He is said to have completed it after 15 years in 1856, and by then Ranjit Singh was long dead. This shawl found its way to the toshkhana of Dogra ruler, Maharaja Ranbir Singh (1856-1885), most probably through purchase.

Kani Shawl

As has been mentioned earlier, the map shawl under reference here was displayed in the Indian section of the Paris Universal Exhibition of 1878. It is a classic depiction of how Kashmiri artisans imagined the city, their abode. The shawl, ‘like a collage, identifies the land with rivers and canals, great gardens, shrines on the riverfront, the tall vernacular houses, magical imagery and a cultural landscape. Given an opportunity, that is how they wished to be known to the world outside and they must have been conscious of how the shawl would travel’.

What is not visible to the naked eye, the shawl has names of major sites, streets and monuments embroidered in Persian script. When the photographs of the map shawl are magnified, the names of the places are found to be neatly embodied with attention to detail in respect of words and alphabets. The detailing of prominent places, sites and monuments would have entailed elaborate sketching, the naqsh. Though the legendary Kashmir shawl was based on kani twill weave technique, the map shawls are mostly embroidered in sozni, the needle-based embroidery. Nothing is known about all this preparatory work of drawings and sketches. Though this is the most essential part of the process of manufacture, it has sadly been given a pass as a ‘minor detail’

M Saleem Beg

The map shawls of Kashmir, the Victoria & Albert Museum possession being one of the finest, are a cherished memory of its makers as also the proud owners who bought them and kept them as their prized possessions. The shawl collection, including the map shawl, would number more than that have surfaced so far, are part of a flourishing but secretive antique trade. We have therefore not known or heard about the last of the line and in times to come many more shawls and as many surprises are in store for the collectors, connoisseurs and art historians.

(Author, a former Director-General of Tourism of the erstwhile Jammu and Kashmir state heads the Jammu and Kashmir Chapter of INTACH and Chairman National Monuments Authority Government of India.)

from Kashmir Life https://ift.tt/3f5HykC

via IFTTThttps://kashmirlife.net

No comments:

Post a Comment