Reviewing Rassul Galwan’s autobiography, Onaiza Drabu sees the book seemingly lost most of its soul during editing that reduced it to a sort of the funniest piece of literature that loved colonial masters

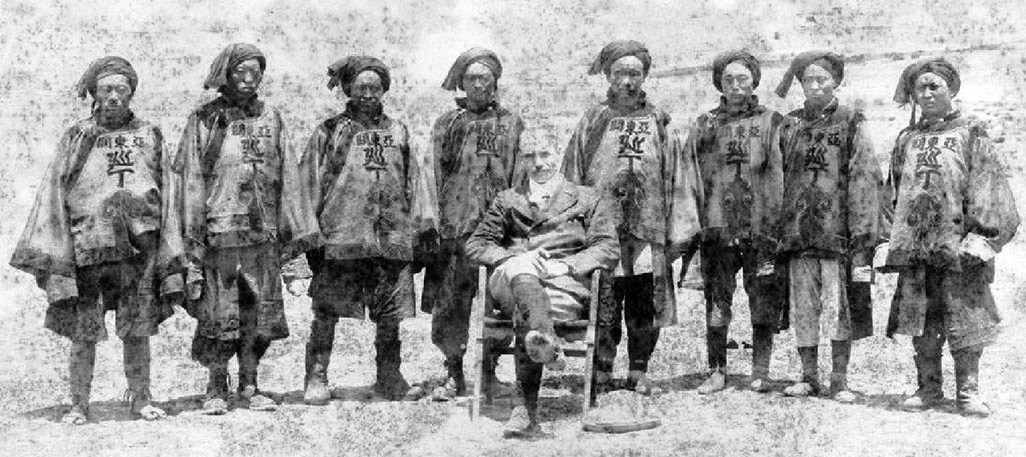

Francis Younghusband with his host companions somewhere in Tibet or Ladakh, a photograph accessed from open sources.

Since 1923, when W Heffer & Sons Ltd published the unusual book Servant of Sahibs: A Book to be Read Aloud, it is still being reviewed. An autobiographical account of Rassul Galwan, a career servant and companion of European and American explorers in their expeditions through Kashmir and Central Asia, it carries an introduction by Sir Francis Edward Younghusband.

The book is edited by the wife of the Sahib to whom Galwan credits the task of ‘making him a man’. It was this husband and wife duo, Mrs and Mr Barret, who were responsible for laboriously assembling, editing and publishing Rassul’s story. It is said that Rassul knew not more than a dozen English words when he met the couple and spent the next fourteen years in the writing, re-writing and exchanging handwritten sheets, till he delivered a manuscript.

Servant of Sahibs presents a remarkably original perspective. The book, written in broken English, is barely coherent and thus more enjoyable when read out loud. The Barretts helped teach Galwan English, but let him maintain the rustic-ness of a native not imposing the King’s English. Younghusband calls the book a way to ‘see their [the natives]ways of looking at things, and looking at us [the colonizers]’.

A reading of Galwan’s work, however, raises the question of whether it is an extraordinary voice heard from the other side, or a well-disguised product of colonial literature in the voice of the other. Being an incidental study of an encounter between cultures, involving asymmetries of power, written during the throes of colonialism, the book faces a methodological problem.

Such a book is also interesting by virtue of being autoethnography; an insight into lives of native Ladakhis

One cannot ignore the possibility of it being a tale intended to establish native authenticity for the colonial mission but far more interesting is the insight it gives us into a society that little has been documented about. It creates a resource for an anthropologist as a genuine source of ethnographic insight.

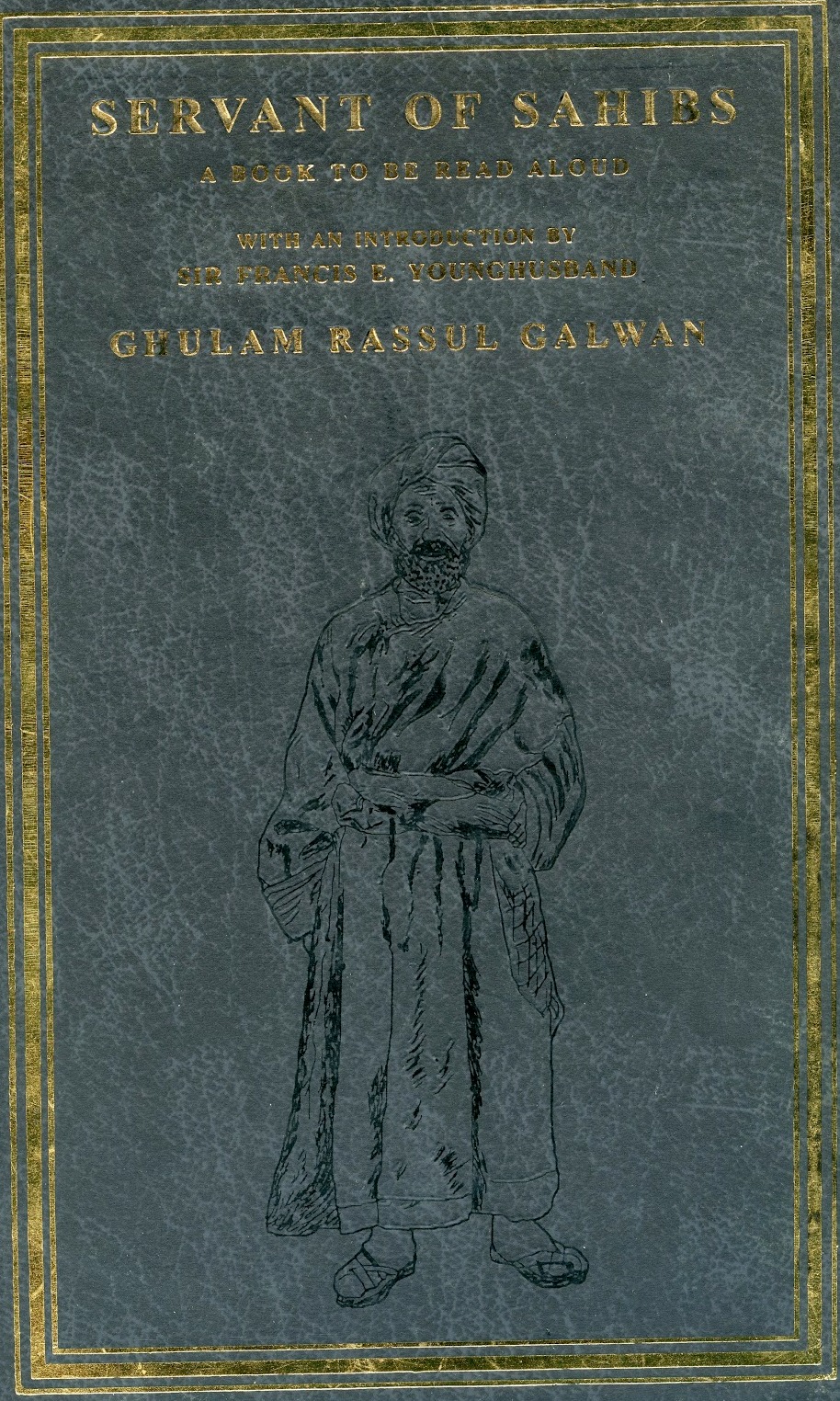

Ghulam Rassul Galwan, a caravan manager and servant of the European visitors whose book was published two years before he died.

I choose to review and examine the book through these two themes. While the first has to do with the social context the book arose from, the latter focuses on the contents of the book. Three-fourths of the original was cut out in the final manuscript. Editorial devices have thus played an important role in shaping the present narrative both by way of exclusion and arrangement of chapters of the disjointed original manuscript of Galwan. Furthermore, the book is guided by the patronizing introduction by Younghusband that sets the tone for it reading as a story of growth through colonial labour.

Although chronologically oriented, the book is carefully edited and revolves largely around Galwan’s interaction with the sahibs with brief records from his own personal life.

For a time when most colonial literature from this place came as travelogues and ethnographies by Europeans to understand the natives, this book is an exceptionally unique account from one amongst them. Literacy and education were restricted to the rich and for a member of the lowest class to come out with a piece of literature edited by a sahib’s wife is an extraordinary feat.

When Younghusband introduces the book by saying that through it, “we understand them (natives) better and find they are after all not so very different from what we were as boys,” we get a sense that the audience he intended for the book were other European sahibs. Upon its release, it was reviewed favourably in the West as a book to lay hands on immediately.

In his note to the readers, Galwan addresses ‘King and Queen, ladies and gentlemen’, who he expects to be the readers and thereby interpreters of the contents of his book. Some argue that he intended the book for a local audience to enhance his social standing and through this note to the upper class put himself in conversation with the rulers of India (see Martijn Van Beek, 1990 Worlds Apart: Autobiographies of two Ladakhi Caravaneers Compared).

Evidence, however, suggests otherwise. The book was meant as an account from the other, the reasons for which can be found by examining the social context of the time.

Servant of The Sahibs, the cover of the book by legendary caravan guide

The 1920s is said to have been a period that saw agitation and social reform against forced labour in Kashmir. Several liberal Europeans supported this agitation. It is against this context we should view Servant of Sahibs. As Butz and MacDonald put it, the book ‘reproduces official colonial discourse on Indian Native labour, which stressed the gentleness and indulgence of masters and the zeal and loyalty of labourers or slaves.’ Very aptly, they summarise the publication of the book with regard to the social situation in one sentence when they say, “The sponsors and publishers of the book intended it to provide an authentic Native contribution to arguments for maintaining existing colonial labour relations (David Butz, Kenneth I MacDonald, 2001, Serving sahibs with pony and pen: the discursive uses of `Native authenticity)’.

Evidently, Younghusband and other reviewers and the publishers, if not always Rassul Galwan or the Barretts, intended Servant of Sahibs to be a glimpse at an authentic and representative native perspective on life as a servant of colonial masters. However, the missing chunks of the book glare at you, conspicuous by their absence. The focus on interaction with the sahibs makes you further suspicious of their contents raising doubts about the authenticity of the current narrative.

Although Galwan meant to write the book as an autobiography, the book largely flows like a travelogue. Out of the 18 chapters, only 6 are about him, his life and his family while the rest are just accounts of his travels.

Some of his interactions were also removed because of the extensive detail he went into. In a footnote on page 70, the editor mentions that ‘Rassul’s memory seems never to let slip a detail in all these earlier journeys. We have omitted much, trying to select those passages that have lingered most vividly in our own memories’.

In yet another note on Page 36, she talks about omitting a chapter entitled, ‘What I got from the Woman Friend’ because was “too crude to print”.

Sir Francis E Younghusband, a 1937 portrait

In the epilogue, one finds more evidence when the editor mentions, ‘the most interesting events of this period are barely touched on’. The missing chapters talk of more journeys, feats, charity, honours bestowed on Rassul and of persistent offers of love made to him by beautiful girls because of his position.

‘Not I am beautiful. I am very ugly a man. They were not love on me, but they think this man is as a head-man; so that they get rich money from me; therefore they give me all the trouble.’

These instances prove how in his initial manuscript he gave rounder account of his life but its editorial devices eventually shaped it into a travelogue.

Although this claim cannot be conclusively proven, what it leaves to be examined is the usefulness of the book as a source of ethnographic information.

One needs to read the texts closely and analyse simple instances to make sense of it as a work of ethnology. Hidden between passing anecdotes from Galwans life and his tell-all style of narration, are wonderful insights about ideas of kinship, stratification and ritual; all of the essential components of ethnographic work.

Writing about his childhood, Galwan once baked bread and went to sleep. When he woke up, he discovered that his goats had polished off the bread leaving nothing for the family to eat. So he wrote in his book: “These our goats were robbers, like our grandfathers.”

His relationship with his mother is an interesting one. Raised solely by her, a mother-son dyad emerges in Galwan’s household. She controlled the finances, managed his earnings and arranged his marriage.

Galwan did not see his bride till the day of his wedding, as was common custom, in his time. ‘I said myself: “How does that girl look? If she is ugly, then what shall I do? Then I shall be ashamed before these Leh girls and boys. They must say: ‘Rassul has got a bad wife.’ But mother likes her, so I must like her.”

It was the mother who chose the girl for she was to live and work for most of her time. The mother’s motivation to get Rassul a bride was to find someone to share the burden of housework.

Saspul Serai an important halting place for caravans, including those of the Shamma, between Khalatse and Leh. A 1931 photograph by Claude Rupert Trench

Rassul had a story to tell yet little means of expression and his patrons guided him in this tale. Other than those briefly mentioned above, he has many more insights about his people, often un-intentional but always intriguing.

‘From tailor place bought little pieces cloth. There I made some sahib and mem-sahibs. Their faces made with white dobe, their hats and boots with bocha (mean one thing make oil from). Myself was servant to sahib.’

Anthropologist Onaiza Drabu

This striking paragraph aptly summarises the book. Rassul here talks about making dolls to play with as a child. The ‘play he makes’ captures the dichotomy this book presents its reader with. Knowing his audience, Rassul could have plugged this bit of information into his manuscript to appease his sahibs. It is also possible that the editors retained this line just to establish the natives’ eagerness to serve. However, it is also likely that colonialism was so ingrained in Rassul’s people that they couldn’t think of themselves as individuals beyond slaves. As with the book, we cannot with certainty claim to understand the background of this paragraph.

As a resource in the field of geography and ethnology, the book contributes by giving a diarists account of the daily life of native travellers. If interpreted in the context of its production, it richly documents a society. However, the books emphasis on asserting it as the voice of the other through keeping the original language intact and a narrative stitched as though he wrote to please, reiterating his indebtedness to his sahibs, must not be ignored. Interspersed with trivial details of life and customs in the mountains, the simple story of Rassul, the ‘bad-trouble-man’, promises to be a challenging and complex piece of literature giving extraordinary insights.

(A Kashmiri anthropologist, Onaiza’s first book is an anthology of Kashmiri folklore. She has also authored a book for Kashmiri children, Okus Bokus, and co-curates Daak – newsletter on historic South Asian literature and art.)

from Kashmir Life https://ift.tt/3ePnXF4

via IFTTThttps://kashmirlife.net

No comments:

Post a Comment