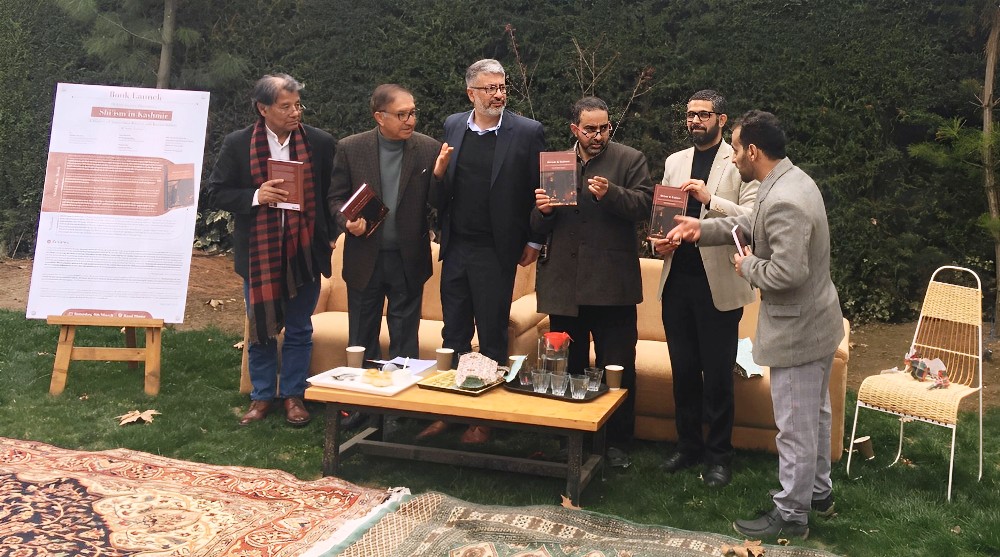

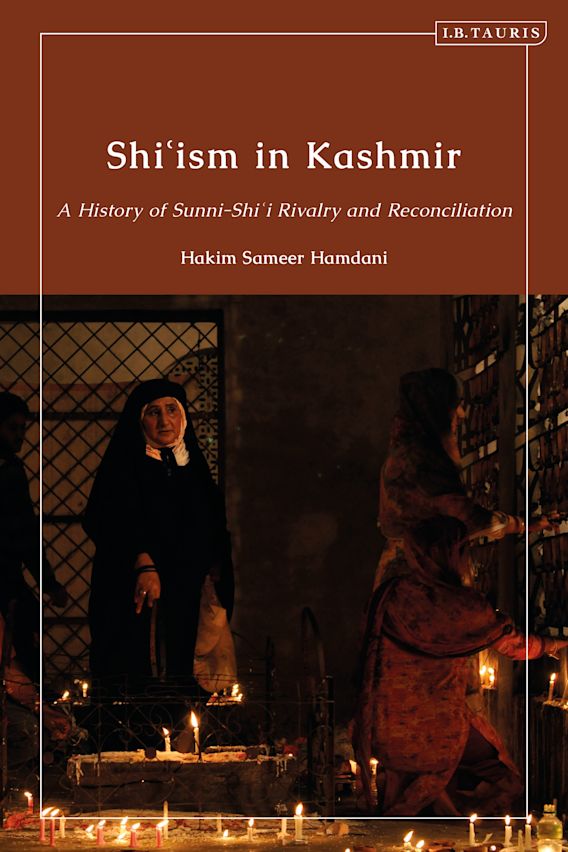

With PhD from the Delhi School of Planning and Architecture (1999) and a post-doctorate from Massachusetts Institute of Technology (2022), Dr Hakeem Sameer Hamdni’s The Syncretic Traditions of Islamic Religious Architecture of Kashmir (Early 14th –18th Century) filled a huge void that in Kashmir’s architectural history. Design Director at the INTACH Kashmir, his latest book Shi’ism in Kashmir: A History of Sunni-Shia Rivalry and Reconciliation is a daring attempt to probe an issue that no scholar has touched ever. A week after the book release, in a freewheeling interview, Sameer details why he choose the subject and what are the net outcomes for Kashmir

KASHMIR LIFE (KL): You are a trained architect with a specialisation in Islamic architecture. You did an excellent book on Kashmir’s medieval architecture that filled a wide gulf after a very long time. What prompted you to get into a very sensitive topic involving Kashmir’s sectarian tensions, an issue that attracted almost no scholar, so far?

HAKIM SAMEER HAMDANI (HSH): That is a question that is asked of me a lot, now that the book has been released. So how do I answer it? Well, let me start by saying that as you rightly pointed out my last book was on the Muslim Religious Architecture of Kashmir. And, it was during that very process of researching, I got interested or maybe intrigued by how our historiography has been used as a conscious tool in framing narratives which project the past as a milieu of religious and sectarian conflict.

This is especially true when we speak about a Shia or a Sunni society during the medieval or even early modern period but then this binary broadly covers how we also perceive Hindu-Muslim relations in the region. But then how historical is this narrative of an antagonistic past?

I do accept that our past is not one which upholds liberal representation, but then the material culture linked with it is replete with examples of what we could call negotiated pragmatism and co-existence. Unfortunately a great deal of our textual history, particularly in the genre of tazkiras (hagiographies) coming as it does from competing centres of power and patronage, often conflates symbols of belonging to a privileged class with religious or sectarian discrimination.

Also, the idea that the book breaches a sort of taboo in our society – a topic which can create divisions is something that I don’t personally agree with. In a way, this ‘let’s not talk about these problematic issues’ assumes that either as a society we are incapable of dealing with sensitive subjects or that as researchers we are so grounded in our own biases and prejudices that the task is virtually unachievable.

I disagree. I am of the view that we have the individual (if not institutional) capacities to as I said in another interview, “historicize or rather contextualize our past in a way that does not seek not-to-hide from differences- but also search, explore for shared similarities- similarities that made us Kashmiris”. That was the origin of a book which engages with a layered past and complex moments of our history with competing interests.

I may be repeating myself here, but to survive as a people, as a civilisation, we need to look at our past with all its dissensions, pain-learn and ensure that we and our future generations will understand and realise the perils of sectarianism, just like communalism are too real and too near to be ignored. We also need to understand that differences will exist and where they exist, they need to be celebrated, not hidden behind a veil of assumed unity and uniformity.

KL: Kashmir’s transition to Islam is well-researched and documented. Would you shed some light on the history and evolution of Shia Islam, or what you call, Shia’ism in Kashmir?

HSH: If I may, I would rather contest this understanding. Yes, we have texts which account for the beginning of Muslim rule in Kashmir. But, this beginning of Muslim presence in Kashmir is still a rather grey area. We have narratives enshrined in texts which came in existence in the sixteenth, seventeenth or even eighteenth century as is the case with Khwaja Azam Dedhmari’s Vaqiati Kashmir, and these texts serve as our only basis of understanding the formative period of Muslim society in Kashmir. So a text like Baharistani Shahi or Tarikh i Kashmir of Malik Haider coming as they do from a Shia space would make us understand that the first Muslim saintly figure of the region Bulbul Shah was a Shia. But then, let us say from the genre of tazkirah, an early account such as Tazkira-i-Airifin of Baba Ali Raina would contest this, and locate early Muslim presence in Kashmir firmly in a Sunni space.

So we have these contesting latter-day texts, some written more than four centuries after the actual event, which forms the basis from which we seek to contextualise the beginning and the nature of Muslim beginning in Kashmir. Academically this has all the making of a grey zone.

Additionally, these texts also seek to firmly locate the beginning of Muslim society in their respective sects. The same is the case of the Nurbaksiyya Sufi order, which emerged in Kashmir during the closure of the fifteenth century. The founder of this order in Kashmir, Mir Shamsuddin Iraqi is seen in most Sunni accounts as the progenitor of Shi’ism in Kashmir, but it is difficult to establish the nature of his Shi’iness. That is why I do write in the introduction that the contours of Shiism during the Sultanate period are not sufficiently explained.

But then my book is not about the medieval period, it explores the nineteenth century instead. So hopefully someone in near future explores these early days of Muslim society in Kashmir beyond modern narratives, which have become frankly repetitive in their narratives.

KL: You briefly talk about revered Shia and Sunni figures. How do you approach how they are represented in histories with miracles directed against the other community?

HSH: Well, I believe that we judge or rather contextualise these events – these miracles in the mizaj of their occurrence not in their objective reality, nor considering our personal beliefs or biases. That has been my approach.

KL: Most of the biased or neutral histories source Kashmir’s sectarian tensions to the 32 years of Chak Rule. There are contested narratives on this. But what is your scholarship revealing because you are a scholar who does not go by hearsay or unsubstantiated events of history?

HSH: Not Chak rule, rather if we were to make an argument for a certain contestation based on the confessional identity of communities it would start during the fag end of the Shahmiri rule. The first recorded case we have of someone seeking to make Kashmir into a single denominational community is that of the Mughal conqueror, Mirza Haider Dughlat. In fact, he proudly states this in his own history, Tarikh-i Rashidi.

But then some of these sectarian contestations that originate in Dughlat’s court make themselves a part of the court politics in the Chak rule also. We have the execution of Qazi Musa during Yaqoob Shah Chak’s brief rule but then even Shia sources; Baharistan as well as Haidar Malik condemn his execution.

Conversely, you have two famous qasidah’s of Baba Dawood Khaki, the principal khalifah of the Suhrawardi saint, Shaykh Hamza Makhdoom, which celebrates Chak rulers, including Yosuf Shah as well as his uncle Husain Shah Chak. Also, we have intermarriage between ruling elites happening all through this period across any perceived sectarian fault line.

A Sunni-centric text, such as the tazkira of Baba Haider Tulmulli writes about two wives of Hussain Shah Chak who were not only Sunnis but also linked in a spiritual line of discipleship to Shaykh Hamza Makhdum. Then again we have the famous case of Habba Khatoon – who is a Sunni, though, like other women poetesses of Kashmir, you cannot locate her in contemporary texts.

So what I am trying to say is yes there are tensions, but then that is not the only history of that period. But, again let me clarify this book is not about medieval Kashmir, I only briefly touch on the period in trying to locate projections of a contested past.

KL: How did the power-play exhibit in the Mughal era of Kashmir after Chak’s were ousted from power? How correct is the notion that the Mughals persecuted Shia Muslims?

HSH: The renowned historian, Irfan Habib does link Akbar and the religious elite at his court with a sectarian, restrictive attitude towards the Shi’a till say around the early 1570s. The execution of Mirza Muqim Isfahani and Mir Yaqub, the envoys sent from Husain Shah Chak to the Mughal court by Akbar can be seen as a part of that attitude. But Kashmir was conquered in 1586 and the emperor proclaimed Din-i-Illahi in 1582. So it was a different Akbar. The conquest of Kashmir does have a certain sectarian undertone but the affair should be seen as part of the gradual process of expansion of centralised authority with vastly superior resources and a borderland region.

The relation between Delhi and Kashmir marks this tension between an expanding centre and a periphery in which, the result occurred on expected lines. Were the Mughals sectarian? No. Despite the bad press that they are getting these days, the Mughals were only interested in one profession ‘rulership’. Their notions of royalty almost overlap with the western notion of the divine right to rule. Jehangir in his comparison between court politics in Istanbul, Isfahan and Agra clearly speaks how unlike in Ottoman Turkey or Safavid Iran, Mughal India was open to both Sunnis and Shias. And, we find presence of Shia subedars or naib-subedars in Kashmir- Iteqad Khan, Abu Nasr Khan, Muzaffar Khan, Zafar Khan Ahsan, Ali Mardan Khan, Ibrahim Khan, Fazil Khan, Hussain Beg Khan, Qawam-ud Din Khan, Abu Mansur Safdar Jung, Afrisiyab Khan.

One should also realise that when the Mughals sought to conquer Kashmir, they were engaged in repeated battles with Kashmiri soldiers – a majority of whom were Shia. We have Jehangir writing about the traders of Kashmir hailing from the Sunni community and the soldiers belonging to the Shia and Nurbakshiyya communities. So in these circumstances, an event like the massacre of the Kashmiri soldier by the Mughals at Macchbawan can be seen as a massacre of Shias because they figured prominently in the Kashmiri army. But that would be a wrong reading. This was a massacre of Kashmiri soldiers seen as a threat to the Mughal Empire who were also Shia.

Again in the reign of Shah Jehan, we have the case of Khawja Khawand Mahmud Naqshbandi who was a Sufi shaykh, connected with the imperial family but was nevertheless banished from Srinagar because of his involvement in a Shia-Sunni riot. Also, a major Shia polemical work against the Sunnis, Al Biyaz-i-Ibrhami was authored in Kashmir under the direct patronage of the subedar, Ibrahim Khan. Yes sometimes the Shia would find themselves under restrictive circumstances but this was mostly a result of individual predilections of the subedar or even the emperor. It is only when we come to close to Mughal rule, with its collapse of central authority that the Shia get targeted because of their faith and also face riots.

KL: What was the state of sectarian tensions in the Afghan rule that is usually seen as oppressive across all sects?

HSH: As you said it was oppressive for all, but at certain moments it could and was more oppressive towards the Shia – also the Hindus. But then we also find the presence of a Shia subedar, Amir Khan Jawan Sher and Kifayat Khan. The Qizilbash component in the Afghan is also indicative of Shia presence though non-native.

The only instance of a prominent Kashmiri figure rising in the Afghan court is Mulla Hakim Jawad, whose son Mulla Hakim Azim would then serve as the chief physician at the court of the Sikh subedar, Shaykh Ghulam-ud Din and consequently Dogra ruler, Maharaja Gulab Singh. Also, under Afghans, we find the presence of a substantial contingent of Iranian Shia traders in the city who also patronised the native Shia community. But, like everything else, the Afghan period is a mixed bag for Kashmir and for the Shia, it is more on the oppressive side.

KL: Your book is focussed on nineteenth-century Kashmir. The era was an extension of Sikh rule in a way. What were the factors that led to the reconciliation between the different Muslim sects? How did it happen?

HSH: In the end, it is a gradual realisation that whether we see ourselves as Shia or Sunni, we are equally discriminated against, and seen as outsider Muslims by the court. The Shia-Sunni faultline is detrimental to our Muslim existence. It is a gradual process but once it commences – gradually from the community elite on either side, it does capture the imagination of the religious classes and more importantly the new class of educated Muslim youth. There are tensions on the way, but the Muslim fight against, what is perceived, as Hindu rule forms the basis of an ecumenical movement within the Kashmiri Muslim community.

KL: Who were the major players in the reconciliation process and what were the key events that exhibited the reconciliation?

HSH: There are many players – you could say the initial interaction between Mirwiaz Rasul Shah and Moulvi Haider Ansari did help in toning down the sectarian faultiness within the city to a level where they could be managed. Also individuals from the dynasty of Mufti Qawamuddin, also Aga Sayyid Musavi who is said to have visited revered Sunni shrines of Kashmir, at Char-I Sharif and Dastgir Sahab.

But, the figure who, in a way, formalises this process is Khawja Saaduddin Shawl. He does emerge as a visionary, who is working towards the formulation of Muslim political consciousness in Kashmir. In 1873, we had the last major Shia-Sunni riot in the city, and within a decade we saw Shawl working to tone down sectarian tensions in the city while also voicing Muslim grievances, hopes-aspirations. This outreach is positively welcomed by the Shia and the main figurehead who emerges in this engagement on the Shia side is Aga Sayyid Hussain Shah Jalali.

As we move towards the first decade of the twentieth century, we see that Shia elders, Aga Sayyid Husain Jalali and Hajji Jaffar Khan sign the memorandum of grievances authored on behalf of the Kashmiri Muslim community in 1907. Similarly, when after the disturbances in the Sericulture department, the durbar bans the daytime Ashura procession in 1924, Shawl helps Jalali in taking out a daytime procession in defiance of the order. This is the first Shia-Sunni march highlighting Muslim unity and was accompanied by two alams (standards) from the revered shrine of Asar-i-Sharif Kalashpora. The move is reciprocated by the Shia who also participate under Jalali’s leadership in the procession from Khanqah-i-Mualla to Char-i-Sharief.

This coming together of the two communities is also witnessed during the BJ Glency Commission of Inquiry in 1931, when the Shia representative, Mulla Hakim Muhammad Ali completely aligns with the demands of the Muslim Conference. In fact, he argues that the Muslim Conference is the sole representative of Kashmiri Muslims, Shia and Sunni alike.

You also see the involvement of Shia Youth in the formulation leading up to, and then in the Reading Room. We have three brothers, Hakim Ali, Hakim Safadr and Hakim Murtaza who are deeply involved with this process. The three are also involved with the organization of Ali Day at Zadibal, which also saw the representation of Kashmiri Sunnis.

I mean a decade earlier Zadibal would be an area avoided by most Sunnis from the city and now you have this public participation in commemorative events taking place in the heart of a Shia space. And, we have individuals such as Justice Sir Abdul Qadir of Lahore from Anjuman-i-Himayt-ul Islam, Raja Ghazanfar Ali of All India Muslim League.

And, then as we move into the 40s, individuals like Munshi Muhammad Ishaq or Aga Shaukat who become associated with this Muslim voice. And then those countless people who unfortunately are never named in histories, but whose contribution is so essential to any social or political movement.

KL: How did the reconciliation display itself post-1931, even though your scholarly work stops in that era, history, as you know, is continuity and sometimes flat.

HSH: Well as you rightly said the period from 1931 onwards is not a subject of my research but yes if you look at some pivotal moments in Kashmiri history post-47, like the Moi-Muqqadas Tahreek you would find active participation of major Shia figures such as Moulvi Abbas Ansari from Srinagar and Aga Sayyid Yusuf of Budgam. Also, the engagement of various scholars and academicians on various societal or religious issues is very visible.

You also find Sheikh Muhammad Abdullah playing a pivotal role in organising a single Ashura procession in the city – an event which was otherwise marked by rival processions between competing religious families within the Shia community. And, then the 1990s threw altogether new challenges and a new set of responses.

KL: For more than half of the millennium, Persian remained the lingua franca of Kashmir to the extent that the rise of Persian led to Kashmir being called the Iran-e-Sageer. Kashmir produced countless Persian intellectuals and poets. How did this Kashmir-Iran relationship impact the sectarian peace or conflict in history?

HSH: There is a Persian poet, who was Shah Jahan’s poet laureate who is also incidentally buried in Mazzar-i-Shura, Drugjan. A Shia, Qudsi is remembered for his naat in praise of the Prophet, Marhaba Sayyid-Ii-Makki Madaniul Arabi– a naat which was regularly recited on mehfil-i-malud amongst Kashmiri Sunnis. I have been told that occasionally it is still recited.

Similarly, we find that the majalis and lessons of masters such as Muhsin Fani, Ghani Kashmir, Mulla Sateh, Lala Malik Shaheed and countless others were attended by people and aspirants across sectarian identities. Ali Mardan Khan and Zaffar Khan Ahsan, both of Iranian origin are celebrated for the promotion of literature. Their sessions were attended by people across any sectarian or communal faultline and then helped in permeating the Persian language amongst sections of the Kashmiri population. Works on ethics, poetics, grammar and a host of other subjects compiled in Persian were studied and circulated without any bias of sect or sectarian identity. I have seen numerous Shia libraries which include codices of tafsir work in Persian that originate in the Sunni circles. Similar is the case in the field of calligraphy, which emerged as a major art form in the early modern period in Kashmir.

from Kashmir Life https://ift.tt/QFa4pBT

via IFTTThttps://kashmirlife.net

No comments:

Post a Comment