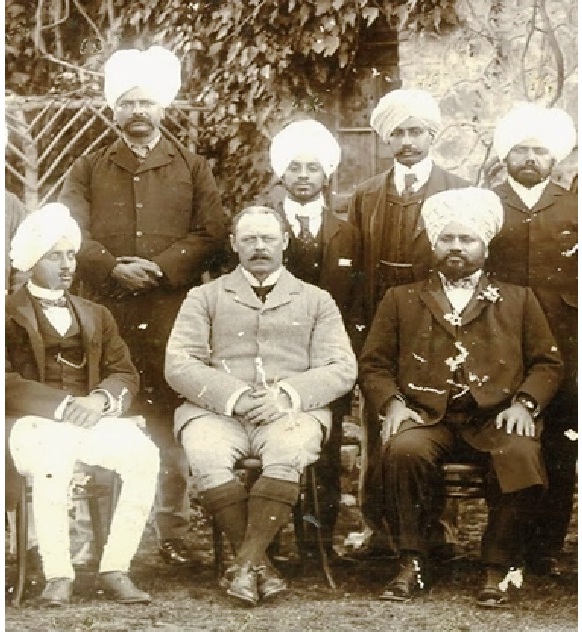

Two years after the British “took over” the governance of Jammu and Kashmir and appointed Sir Oliver St John, the first British Resident on September 25, 1885, Andrew Wingate was appointed the land Settlement Officer on January 15, 1887. Of the state’s 28 tehsils he did land settlement in Lal and Phak Parangna’s leaving the gigantic exercise to Walter R Lawrence. In his preliminary report, however, he detailed how the land, crops, markets and people were consumed by the middlemen unleashed on the peasantry

“The general result of the last 70 years appears to be that the population is now little more than half of what it used to be. That it is a considerable loss, there can be little doubt. Traces of disused irrigation and of former cultivation, ruins of villages or parts of villages, of bridges, &c, local tradition, all point to a greater prosperity, which by the end of the Sikh rule in AD 1846 had well-nigh disappeared.

Feeding People

To maintain the population, two devices have been resorted to, both I believe of old date. The first, prohibiting export of rice is still in existence. The second, prohibiting any Kashmiri crossing the passes was removed during the last famine. The door of hope was, however, opened too late for of the numerous refugees few succeeded in reaching the open country and consequently few came back. Since then, numbers of Kashmiris visit the Punjab every winter where they find employment and save on their wages, returning in the early spring to cultivate their fields, generally bringing with them some cloth or other trifle for their wives, but getting frequently roughly handled by the customs’ clerks for their pains.

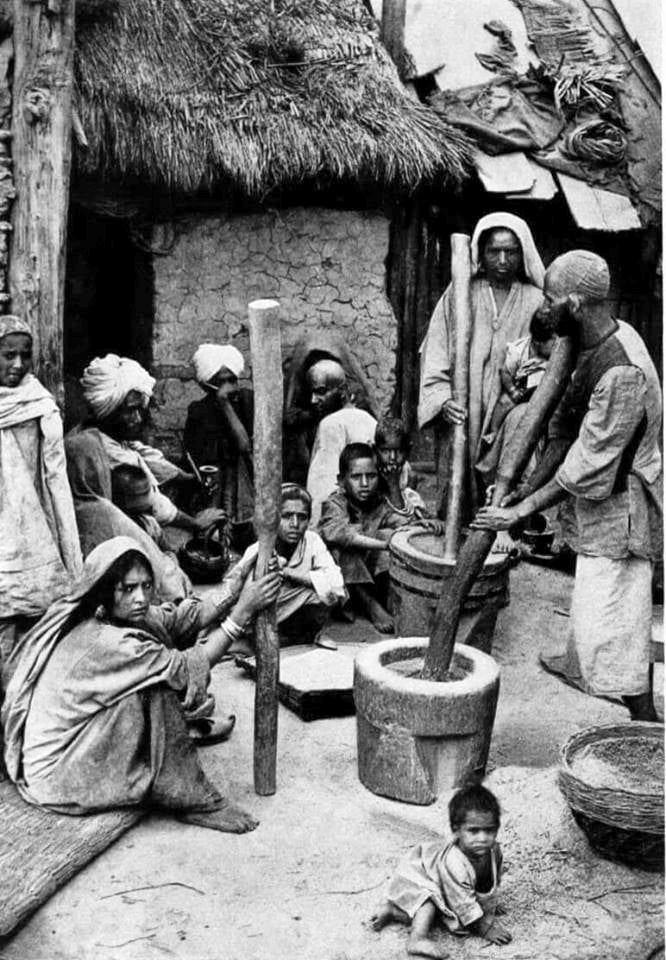

Kashmiri requires more and more frequent nourishment and warmer clothing than his brother of the plains. Not only does the climate necessitate more but the Kashmiri has the body and strength of an elephant. The collectors of shali often pay insufficient attention to this point, and as the aim is to collect for the use of the city all that can be safely taken, they are apt, acting on their experience of what a family consume in the plain, to leave too little to properly support and multiply the agricultural population. (page 16)

I saw mobs struggling and fighting to secure a chance of getting a few seers of the government shali, in a way that I have not witnessed since the great famine of southern India.

Stagnant Prices

I have found it impossible to obtain any record of bazar prices, but I believed I am correct in saying that before AD 1846 the normal price of shali was about eight annas per kharwar, and that it varied with the harvests. For example, during the famine of AD 1861-33, the price rose greatly, and oven after AD 1833, it remained for some time as high as Rs 1.5 per kharwar. Whether the kharwar was reduced to 15 traks instead of 16 traks then I have not ascertained. Shortly after Maharaja Golab Singh assumed control, the present system of collecting shali in large granaries in the city and selling it by retail through government officials appears to have been introduced, and the price of shali, with a brief interval about AD 1879 when it was raised to Rs 1.5 has remained stationary at Rs 1.25 per kharwar of 15 traks = two maunds and one seer of standard weight at 80 tolas per seer.

For over 40 years the system has been sufficiently profitable to support a large body of the pandit population of the city in idleness, and the government has gradually become on the one side a farmer working with coolies under a management closely approximating forced labour, and on the other side, a gigantic bannia’s shop doling out food to the poor in exchange for their coppers, and keeping with every cultivator an account showing what is taken from him whether in the way of grain, oil, wool, ponies, cows, &c, and what is given to him in the shape of seed, plough-cattle, cotton or wool to spin and weave, and a hundred other petty details. (page 17)

When I told your Highness in Darbar the price of shall must rise with the state of the harvest, and must probably be often higher than rupees two chillki, a shiver went round the officials, and your Highness said you would not dare to raise the price so great would be the outcry. I can only say that a country cannot go on feeding a semi-idle host at less than cost price and somebody must be a loser. The cultivators have lost much, even the interest to cultivate, and now the loss is falling on the State. (page 26)

The Booty

Under the Sikhs, the State took a half-share of the kharif crop and in addition four traks per kharwar and on account of the rice straw and the vegetable produce of’ the Sagazar” plots, the whole of which were kept by the Asami and were supposed to be free of assessment, Rs 1-9-0 per cent, was added to the total. The patwari and kanungo got 4 a trak per kharwar between them.

Inferior village servants got something. Nazarana was levied four times a year, and tambol (about two per cent) was taken on occasions of marriages in the ruler’s family. The villagers had also to feed the state watchers of the grain, called Shakdar. Non-resident cultivators paid a little less and Pandits and Pirzadas only paid two extra traks instead of four.

For the rabi and kimiti crops, all classes of cultivators were taxed alike, and in addition to the half-share, three traks per kharwar were taken under the names of extra cesses. The kimiti crops appear to be those that have always had a money value and are tilgogal, sarson, tobacco, cotton, linseed, saffron and the like.

For other crops, whether kharif or rabi, the collection might be in kind, or the villages might be farmed out. But I can find no trace so far of any crop rates. Walnut oil, fruit-trees, and honey have also always been taxed. Under the above, the State share was not less than three-fifth of the gross produce and what the cultivator actually retained was certainly less than two-fifths and probably only about one-third. The abundance of fruits, berries, and nuts, the extensive grazing area, and forest produce, enabled the cultivators to live, but an assessment so heavy as this would extinguish all rights in land, would render land valueless and would reduce a population forcibly confined within the valley to the condition of tenants-at-will. (page 18)

Since the times of the Sikhs, the pressure has been undoubtedly relaxed but it must still be pretty severe when cultivators, are found ready to sell whole villages for no other equivalent than the protection of a powerful name. Many of the Mukaddams, or heads of the villages, are very intelligent, but when it comes to seeing their children stinted of food, with hearts sickened by deferred hope, they sign away fatuitously day by day such rights as they possess. During Maharaja Golub Singh’s rule (AD 1846 to 1857) the Sikh procedure was followed, but some slight relaxations were made in favour of land newly cultivated, for large areas were lying waste.

His Highness was fond of horses and a number of grass-rakhs were reserved from cultivation.

Under Maharaja Ranbhir Singh, circles of villages were annually farmed out to contractors, called kardars. About 1865 the extra traks per kharwar were reduced for all Pandits and Pirzadas for a time to only one trak.

From about 1869 the practice of contracting with the Mukaddams or with the Zamindars gradually established itself in place of the farming system, and only two extra traks came to be levied instead of four.

In 1873-74, the village contracts seem to have been divided up into asamiwar khewats” or cultivators’ accounts, and either produce or cash was taken from each man.

In 1875 the harvest was a bad one, and the state took two shares of the produce and left one only to the cultivators. Next year fresh contracts were entered into either with Mukaddams, Kardars or cultivators and two traks per kharwar were again added to the assessment, besides an aggregate tax of Rs 9-12-0 per cent, if paid in cash or nine kharwars 12 traks per hundred kharvvars if paid in kind. This tax included a number of items, such as support of the Palace-temple, the abolished kanungo’s share, and so on.

In 1877 the scarcity began and the new contracts broke down and so the State collected in kind only, and this practically continued till 1880 when a new asamiwar khewat was made based upon previous years’ collections as estimated in cash but payable either in produce or cash as the cultivator was able. This khewat or cash settlement is supposed still to be valid, but after the good harvests of Samvat 1937 and 1938 the settlement was thought to have been too easy, and so it was raised by Rs 8-9-0 per cent, the chief item of the increment being Rs 6-13-0 for a pony tax, which might be paid in ponies instead of money, and in place of the Rs 1-9-0 per cent, formerly levied for fodder, the cultivators were required to give five kurus of rice-straw per 100 threshed.

This settlement includes all cesses except the tambol and nazrana. In 1885 the Rs 8-9-0 per cent, tax was remitted, and so now the khewat of S 1937 is supposed to have been reverted to, with the exception of the five kurus of rice-straw which are still taken.

In 1886, one seer per kharwar, formerly payable to the zillalidars, was made payable to the State, who appointed paid chowkidars. If this revenue history is not very correct, it must be remembered that access to the revenue records has been denied me. (page 19-20)

Grain Free Market

There are neither grain shops in the bazar nor bannias nor bankers. I do not know whether it is an offence to sell shali but cultivators are afraid to do so, and in tehsils nominally under a cash settlement and with an abundant harvest my establishment have once and again been literally starving and the only way they can get food is by having it sent out, rice, atta, dall from the government storehouses in Srinagar to the tehsildars who thereupon sell to my men for cash. My men still find difficulty in procuring the necessaries of life, and only very urgent representations at headquarters have secured the supplies necessary to stop the angry and to me humiliating clamour of my subordinates to be allowed to buy food for ready money. (page 17)

Coolies, Not Cultivators

I have been told by the highest and most trusted officials in Srinagar that the Kashmiri cannot be trusted with shali because he would eat the whole of it, that he will not plough unless the tehsildar gives him the seed and makes him, and that without this fostering care of government he would become extinct. The truth being, that he has been pressed down to the condition of a coolie cultivating at subsistence allowances the State property.

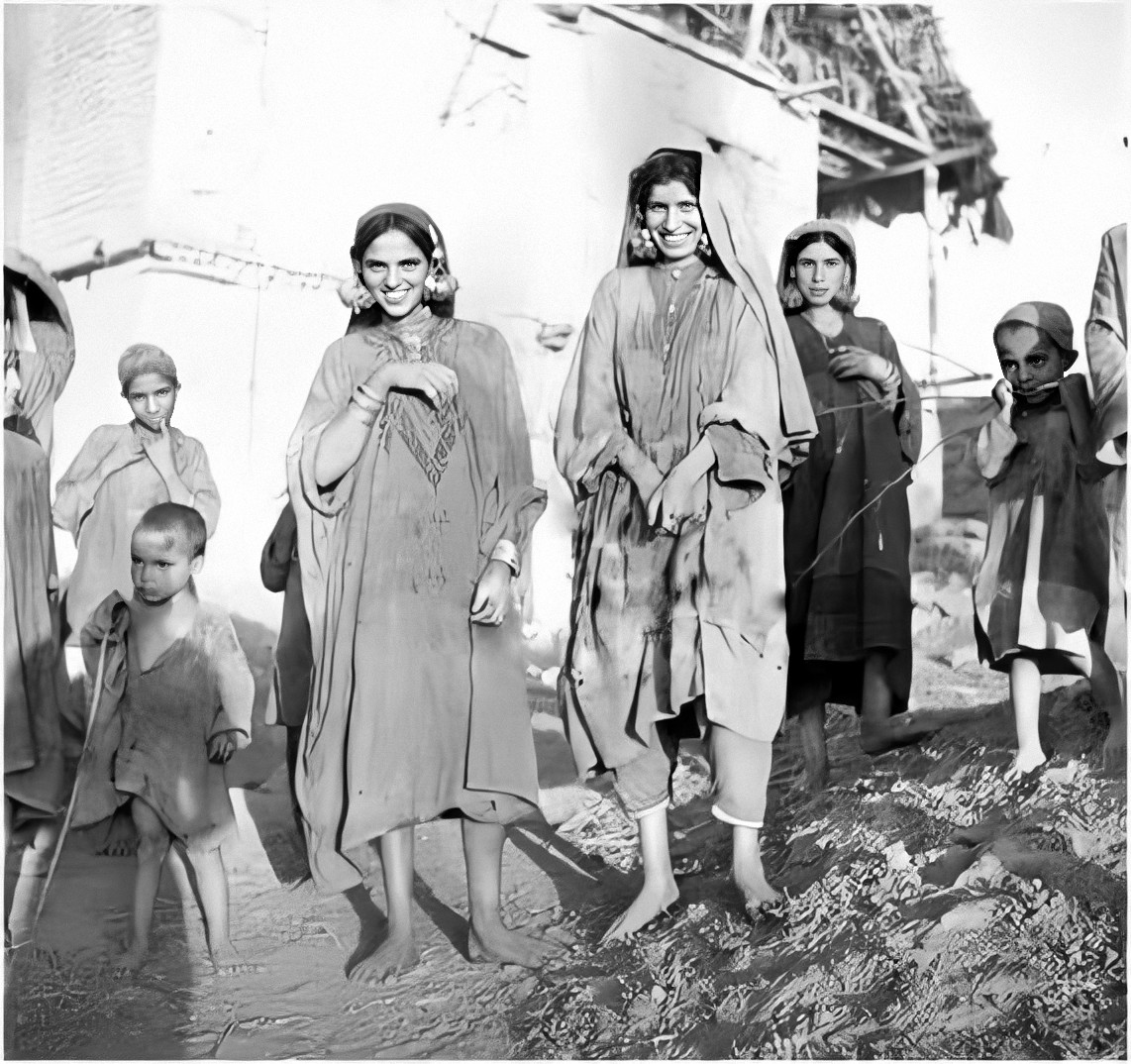

The Kashmiris are called cowardly because they have lost the rights belonging to the peasantry elsewhere and tamely submit to be driven like sheep before a sepoy. But it is useless to expect that a small population forming an isolated state that looked only to its hills for protection could withstand powerful neighbours, like Afghans or Sikhs, or that so distant and inaccessible a province would not be ruthlessly ground down under the endless succession of Governors that have enriched themselves in this valley. The Kashmiri is strong and hardworking, but his spirit is dormant, and he is grudged the quantity of food the climate makes necessary but which a short-sighted policy considers gluttonous, and consequently, he is being closer pressed every harvest. (page 19)

Last year I found in the cash-settled tehsil the standing crops, reaping, and threshing, as strictly guarded as if there was batai assessment with this serious difference that the cultivator did not know what share of his shali would be left to him. (page 25)

Peasant Loot

It may be easier now to understand why the Kashmiri cares naught for rights in land, why his fields are fallow or full of weeds, and manure and water neglected, why he has, as I can well believe, even to be forced to cultivate? The revenue system is such that whether he works much or little, he is left with barely enough to get along on till next harvest. He is a machine to produce shali for a very large and mostly idle city population. The secret of the cheap shali is because if the price were allowed to rise to its proper level, the whole body of pundits would compel the palace to yield to their demands. (page 26)

The ignorant Mohammadan cultivator has not only no one he can call friend, but everyone, whether Hindu or Mohammadan, of any influence, is against him, for cheap bread by the sweat of the cultivator’s brow is a benefit widely appreciated. The Mohammadan cultivator is compelled to grow shali, and in many years to part with it below the proper market rate, that the city may be content. If the harvest is too little for both, the city must be supplied and is supplied by any force that may be necessary and the cultivator and his children must go without. That is the explanation of the angry discontent that filled the valley during the famine. The cultivator is considered to have rights neither to his land nor to his crops. The pundits and the city population have a right to be well fed, whether there is famine or not, at rupees two chillki per kharwar. I said everybody of influence was against the cultivator. (page 26)

Enforced Weave

The anti-climax is reached when cotton is served out to the villagers to be made into army clothing, and when the villagers can make nothing of the rotten commodity, they are charged for the cotton supplied at Rs 14 chilki per kharwar, with interest at over 14 per cent. (Page 27)

Internal Displacement

It has been described how the revenue system leaves the cultivator, without protection. His one concern is to get enough to eat and when he fails in one tehsil he betakes himself to another. Consequently, hereditary occupants are few and if any proof were wanting of the unsatisfactory condition of agriculture it is the fact that large numbers have only cultivated their present lands for a few years. In a highly fertile valley to find the peasantry roving from village to village is a clear sign that the administration is faulty.

This constant search for a rest never found, leads to two things; first, that much valuable land is annually thrown out of cultivation, and secondly that the people endeavour to shelter themselves behind any influential name. Consequently, since the death of Maharaja Golab Sing, from which date central authority appears to have been weaker, there has been a steady and latterly rapidly increasing transference of land from the cultivating to the non-cultivating classes and a landlord element is intruding itself between the cultivator and the State. (Page 27)

The Modus Operandi

As soon as a man has got any land he proceeds first to oust all the old cultivators so as to destroy any proof of the land having been cultivated when he entered upon it, and second to extend his ownership over every bit of land in the neighbourhood he can lay hands on. An instance will speak for itself. A tehsildar cast his eye upon a fine village within his charge, close to Srinagar. There, were six or seven kharwars fallow and waste, which supplied a pretext for developing the country and improving the revenue by applying for a chak. He had good influence at headquarters and his friend the Diwan, about five years ago, gave him a mukarrari patta for 20 kharwars at the usual rates of Rs 12 for wet and Rs 6 for dry land, but the tehsildar took care to get it inserted that all the land was dry… For some such trifling sum he is in possession of 29 kharwars of fine land of which 20 kharwars are irrigated and chiefly shali, so that even at the nominal rates of the patta, he should be paying about Rs 300. Some of the villagers objected to their land being thus appropriated and specially to the water supply being controlled for the benefit of the land seized, but the tehsildar speedily reduced them to reason by getting their revenue demand raised by between 30 and 40 per cent, and the village is now labouring under heavy outstanding balances. This leads to cultivators disappearing and as they disappear their fields are quickly added to the chak. He is now trying to turn the villagers out of their abadi and to house his own cultivators there instead.

Another cultivator dies, his children are young. The neighbouring chakdar immediately takes possession under an agreement to be answerable for the revenue and to restore the land when the children grow up. Another chakdar makes a quarrel about his boundary and works in a few kharwars of land that way. One cannot ride in any direction without hearing complaints of these annual accretions to chaks. (page 30-31)

When I saw the village its fine lands were mostly lying unsown and its houses empty. If it is inquired why the old cultivators do not now return it is because the outstanding balance against the village is enormous, and last year I found the tehsildar trying to secure the entire crops of the miserable few who were left in a vain attempt to reach a sum equal to about one-third of the demand, but with the more likely result of ensuring the complete desertion of the place. As I pointed out villages do not tumble down in this fashion without a cause and the cause is bad administration, and that I fear sometimes with a definite purpose. (page 32)

The son of an influential official took a contract in the old days for two villages. Next year he petitioned the Vazir Wazarat that he was being hindered paying the revenue of the villages which are his property. The Vazir Wazarat submits the case for orders and an endorsement is written across a corner that petitioner is to be allowed to pay the revenue of the villages, and here the writer takes care to repeat the words of the petition, which are his, in milkiyat and zumindari. Now whatever rights cultivators may have it is certain that ownership of villages, unless conferred by the Darbar by sanad, does not exist in Kashmir. Having got so far, the next step was to take an ikcrarnama or agreement from the villagers that he is the proprietor. Armed with these documents, he requests me to record him as proprietor of both villages. On inquiry, of course, it is ascertained he is a mere contractor of revenue and that one-half the villagers deny his claims, and the other half were bought over by a promise that they should be protected from seizure for forced labour. (page 32)

It is to be clearly understood that the interests of the Darbar and the interests of the cultivators are identical and that the interests of all middlemen whatsoever, whether revenue farmers, telisildars, or quasi-proprietors, are inimical to both. The cultivators desire more food and the Darbar, more revenue, and the whole pundit class live by stinting both. (page 37)

The Commission Crisis

I cannot conclude without representing that the conditions which environ my department are most unfavourable to good work. Your Highness’s back is no sooner turned than the measurers again suffer from obstruction. Coolies arc seized, not only from villages under survey, contrary to your Highness’s positive command, but even the parties are interrupted, and chain drawers and flag bearers are dragged away. Recently the judge has begun to receive complaints against my subordinates for assault and the like and to issue process against them. Considering they are Punjabis working for your Highness in a country where they cannot even understand the language, and that a dozen Kashmiris can be made to give any evidence an offended chakdar or official instigates, my subordinates are not likely to consent to work absolutely alone in isolated villages with the prospect of appearing in Criminal Courts. My subordinates have a most difficult task and are exposed to every temptation. (page 45)

from Kashmir Life https://ift.tt/DLX9AB8

via IFTTThttps://kashmirlife.net

No comments:

Post a Comment