Italian traveller Marco Polo visited Kashmir somewhere in 1271-75 and recorded a few passages about the life and culture of a place rendered inaccessible by mountains. Muhammad Nadeem offers the text and context to these brief writings that are a key source for historians to deconstruct the evolution of Kashmir as a society

The Venetian explorer Marco Polo’s fascinating account of his travels through Asia in the late thirteenth century provides a valuable window into medieval Kashmir. He recorded descriptions of the region that capture key details about Kashmir’s geography, people, culture and history. By examining Polo’s account alongside other historical sources and records, modern scholars can further understand and contextualise his perspective on this strategically located region.

Polo’s Commentary

Marco Polo referred to Kashmir in several passages, offering glimpses into how he and his contemporaries viewed the distant kingdom. He mentioned Kashmir when recounting the Mongol leader Nogodar’s daring raid from Badakhshan into Northwest India in the 1260s. Travelling through lands like Pashai and Ariora (likely corresponding to the modern-day Kunar Valley and Agror), Nogodar invaded Kashmir after losing “a great number of his people and his horses, for the roads were very narrow and perilous.” This aligned with the treacherous gorge geography protecting Kashmir that historians have analysed.

Later, when describing his return journey towards Balasham after visiting Badakhshan, Marco Polo paused to provide basic details on Kashmir’s location and people.

It should be understood, that he conveyed that when the Great Khan lived in his palace and encountered rainy or cloudy weather or any other unfavourable conditions, he relied on wise astrologers and sorcerers. These individuals, through the might of their wisdom and incantations, were said to drive away all clouds and bad weather from the palace, ensuring that the weather remained fine above the palace while the bad weather was directed to an entirely different place.

“These wise men who perform this wonder are called Tebet and Kesmur, which are the names of two races of idolaters. They know more of diabolical arts and enchantments than any other people on earth. What they perform is by the art of the Devil, but they make others believe that it is done through their great sanctity and by the help of God. “These people go about all dirty and filthy, never giving a thought to their self-respect or to those who see them; their faces are covered with mud, and they never wash or comb their hair, but ever go about in an exceedingly sordid condition. They also have another custom that I will tell you of: when someone is condemned to death and executed by the authorities, they take him, and then cook and eat him; but if a man dies of a natural death, they will not eat him.”

While fancifully exaggerating some details, this passage broadly matched other historical accounts in locating Kashmir as an easterly neighbour to lands like Wakhan and Badakhshan (Balasham).

A Week Long Visit

Marco Polo is situated in Kashmir about a seven days’ travel from Pashai, or the Kunar Valley region. The people he described as Kesmur displayed some resemblance to the followers of Tibetan Buddhism that dominated Kashmir and neighbouring regions during this era. However, Marco Polo also echoed a tendency among medieval European travellers to exoticize unfamiliar non-Christian faiths. He ascribed magical powers to Kashmiri religious specialists that might seem outlandish from a modern perspective.

Marco Polo’s most extensive discussion of Kashmir came even later in his travelogue when he provided historical information he had compiled. According to him, Keshimur was a province where the people were idolaters and had their language.

In his words: “The people here are wonderfully clever devil-charmers. They make their idols speak and, by means of charms, they make the weather change, causing a thick darkness to descend. With their charms and talents, they perform such marvels as no one can believe who has not seen them. I will add, indeed, that they are the principal idolaters, and that idolatry was born amongst them.”

He explained that from Keshimur, one could go to the Sea of India. In Kashmir, he wrote: “The men are dark-skinned and lean; the women are as beautiful as dark women can be. Their diet consists of meat, milk, and rice. The climate is temperate, without an excess of heat or cold. There are many cities and towns, as well as forests and deserts, and such formidable passes that they are afraid of no one. They are independent and have a king of their own who governs them according to justice.”

Kashmiri Hermits

According to Marco Polo, the people of Keshimur had hermits of a kind, who lived in hermitages, practised great abstinence in eating and drinking, and remained surpassingly chaste.

“They are exceedingly scrupulous about committing sins forbidden by their law, and their fellow countrymen consider them very holy. You must know that they live at a very advanced age, and it is for the love of their idols that they practice such strict abstinence. They also have numerous abbeys and monasteries of their faith, where the brethren lead very strict lives and wear a tonsure like our Dominicans and Minorites,” Polo recorded. “The people of this province kill no animals, nor spill blood. However, there are Saracens living among them who slaughter the animals for them so that they may have food.”

The Trade

Regarding trade, Marco Polo noted that the coral exported from their countries found a better market there than anywhere else. He mentioned that if one were to proceed for twelve more days’ journey, they would reach the lands where the pepper grows, near the country of the Brahmins.

However, he decided not to proceed further and stated, “We will cease speaking of this province and district, for we would otherwise enter India, and I do not wish to do so now. We will tell you everything about India in the proper order on our return journey. At present, we shall therefore return to our provinces, in the direction of Balashan, as we cannot proceed in any other direction.”

In this extended treatment, Marco Polo provides reasonably accurate details about Kashmir’s climate, terrain, access to major trade routes, cultural practices and political status during his era. Kashmir was strategically positioned along vital Silk Road trade networks connecting India, Central Asia, China and beyond.

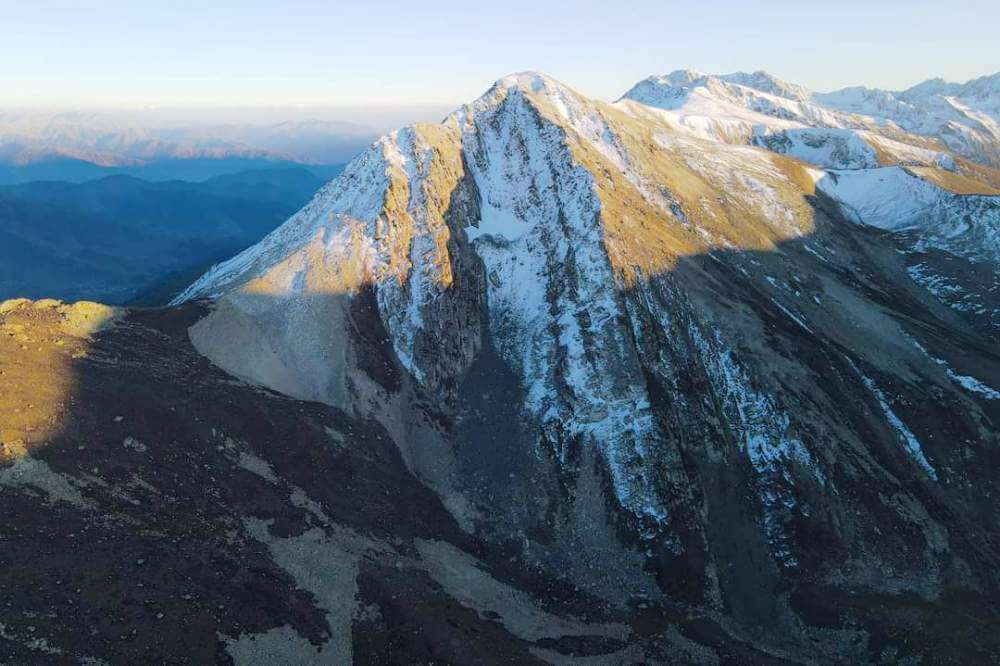

Located high among the Himalayas, it enjoyed a mild “temperate” climate compared to the sweltering lowlands of Northern India. Kashmir’s mountainous geography, mentioned again by Marco Polo above, helped it maintain independence from regional powers for much of its early history.

However, Marco Polo displays more dubious knowledge when describing Kashmiri society and religion. He compares Kashmiri ascetics to European Christian monks, though local religious orders would have followed very different spiritual traditions at this time such as Shaivism or Mahayana, Vajrayana Buddhism.

His claim about animal sacrifice supplanting Buddhism also diverges from historical reality in thirteenth-century Kashmir. Nevertheless, his association of Kashmir with mystical practices echoes the Shangri-La exoticism that still colours modern popular imaginings of this region.

Other Historical Sources

How reliable are Marco Polo’s claims and descriptions regarding medieval Kashmir?

Some sources claim that he did not visit Kashmir himself but relied on other travellers’ records to construct his own and that “due to Marco Polo’s lack of firsthand experience in the region, the accuracy of his account depends greatly on the quality of information gathered from his Mongol and Persian sources.”

Unfortunately, historians and geographers face a challenge when trying to verify Marco Polo’s claims about medieval Kashmir. This is because there are no accurate existing historical records of Kashmir during the exact time Polo wrote about.

The most detailed local text from that period, Kalhana’s Rajatarangini, which covers Kashmir’s thirteenth-century history, is itself considered more of a fanciful story than an accurate historical account. Kalhana composed this Sanskrit chronicle in 1148-50 CE, documenting Kashmir’s dynastic lineage and crucial events from its mythical origins through the twelfth-century reign of King Jayasimha.

The later scholar Jonaraja continued the Rajatarangini with additional material on the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, while the Kashmiri historian Śuka, who wrote after Jonaraja, covered the late fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries. Even though these sources don’t align perfectly with Marco Polo’s time, they serve as essential references for modern researchers trying to assess the accuracy of Polo’s descriptions of medieval Kashmir by comparing his claims against accounts from around the same period.

However, certain basic claims in Marco Polo’s account stand up to scrutiny when cross-checked with details from the Rajatarangini’s thirteenth-century sections and other Persian and Central Asian histories. His descriptions of the geography and climate resemble Jonaraja and Śuka’s presentation of Kashmir as a fertile valley ringed by forbidding mountains. Dates and locations related to the incursion of Mongol leader Nogodar outlined earlier also match known raids recorded in multiple texts, though Jonaraja lists the invader’s name as Targhi instead of Nogodar. Both writers emphasise the plundering and violence wrought by these invasions from the northwest.

However, Marco Polo’s understanding of religion and society in medieval Kashmir shows more significant flaws when contrasted with indigenous accounts. The Kashmir of this era identified predominantly with both Hindu and Buddhist traditions, transitioning from a focus on Shaivism to the rising influence of Tibetan Buddhism brought by scholar-adepts like Śakyāśrībhadra. The syncretic mixture of faiths Marco Polo ascribes to thirteenth-century Kashmir corresponds only loosely to the religious developments traced in detail across the Rajatarangini’s dynastic history. Similarly, Marco Polo offers no mention of the long rivalry between Kashmir’s Hindu and Buddhist communities that surfaces repeatedly in the Rajatarangini’s political drama.

In highlighting exotic magical practices tied to Kashmir, Marco Polo seems to perpetuate stereotypes about tantric mysticism also found in Western medieval texts as diverse as Odoric’s Travels or Wolfram von Eschenbach’s Arthurian epic Parzival. This reductionist focus obscures the more nuanced syncretism and philosophical depth underlying Kashmir’s spiritual traditions. Nevertheless, Marco Polo deserves credit for attempting to faithfully convey the “marvels and miracles” that so captured his and his contemporaries’ imaginations half a world away.

Conclusion

Marco Polo’s account of Kashmir, though rife with fanciful stereotypes, ultimately provides remarkable insights into this storied region’s past. Details on its geography and strategic placement align with the corpus of known historical evidence. Flourishes about its exotic culture reflect in part romantic fantasies prevalent in medieval European writings. By reading his text critically alongside indigenous records, modern scholars can identify Marco Polo’s reliability as an observer and glean precious context regarding Western perspectives on alien lands during his era of early globalization.

The passages highlighted in this analysis represent only a portion of Marco Polo’s references to Kashmir in his extensive travel memoirs. But they illustrate the opportunities and obstacles involved in extracting accurate history from European travelogues about unfamiliar locales.

Marco Polo captured Kashmir’s allure for foreign visitors, even as he misinterpreted key aspects of its society. Evaluating his account alongside Kashmir’s own texts helps assess both the medieval West’s limited grasp of distant realities and Marco Polo’s diligent efforts to convey true understanding across immense cultural divides.

The post 1270s: Marco Polo’s Kashmir appeared first on Kashmir Life.

from Kashmir Life https://ift.tt/U2fSLs6

via IFTTThttps://ift.tt/vlyIsj6

No comments:

Post a Comment