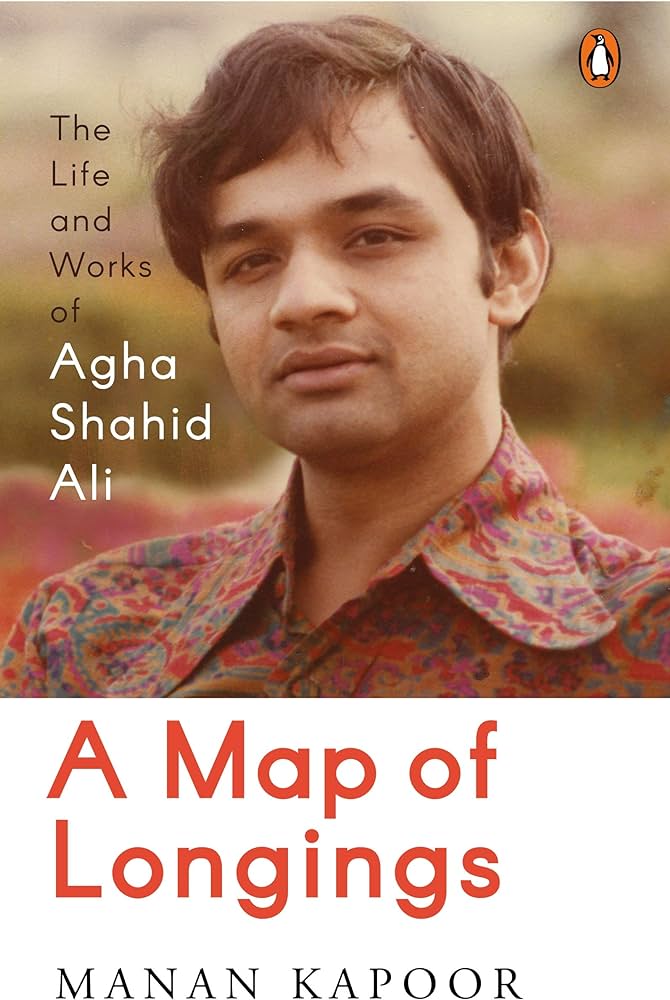

Manan Kapoor’s book on Agha Shahid Ali is a refreshing long story about the leading Kashmir poet whose indelible footprints in English literature will outlive many generations, writes Muhammad Nadeem

Manan Kapoor’s first book, a novel, The Lamentations of a Sombre Sky was set in Kashmir. His second, A Map of Longings, spans the life of Agha Shahid Ali, and his family history. It also covers various aspects of Shahid’s life as an adolescent, as a college student in Delhi, and as a poet and professor in India and the US. The story of his growth as a poet is interspersed with anecdotes from his experiences that led to particular lines in certain poems and sometimes an entire collection.

The Upbringing

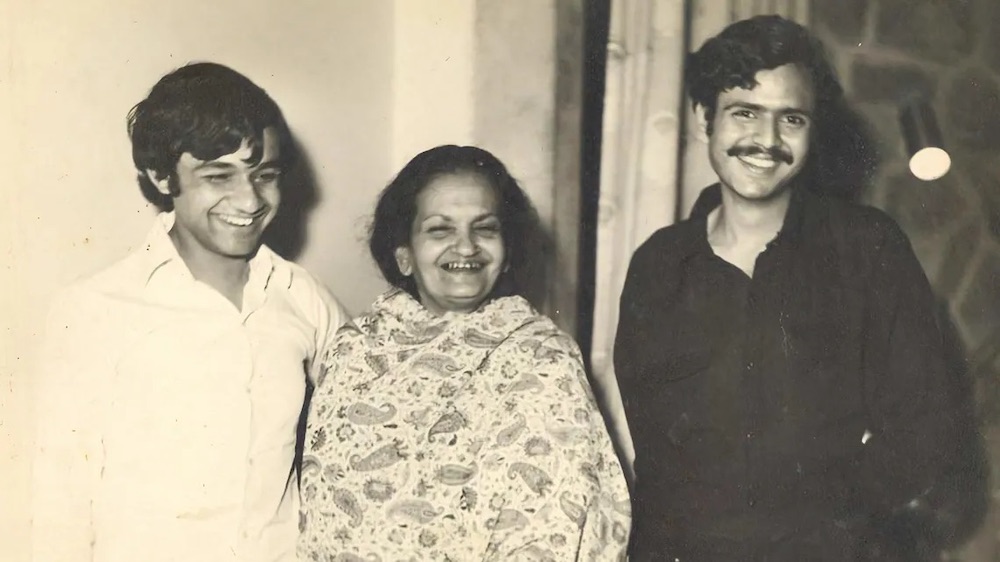

As a young child, Shahid dressed as Krishna for Janmashtami at the refugee home run by his mother Sufia Agha in Kashmir. Though unaware of Krishna’s meaning, he was the centre of attention among the Hindu and Sikh women residents. When older, Shahid realised Krishna’s significance and went through a Krishna phase, wanting to build a temple. Dressing as Krishna became a precious lifelong memory tied to his mother’s care. The experiences at the secular home amidst partition violence shaped Shahid’s admiration for the Hindu god. In later writings, Shahid fondly recalled being “crowned Krishna” by his mother among the refugees.

Shahid Ali grew up in an intellectually stimulating and elite environment in Kashmir. His parents, Sufia and Ashraf, filled their home with art, books, music and poetry from diverse traditions – Kashmiri, Urdu, Persian, English, Hindu, Muslim, and more. He absorbed it all, dressing up as both Krishna and Jesus in homemade shrines. His father’s socialist views led Shahid to briefly attend public school before moving to a Catholic school. Shahid impressed teachers with his knowledge of Western pop music. His family held mushairas featuring great poets like Faiz Ahmed Faiz, whose work Ashraf recited. Shahid gained admiration for public figures like Mujeeb and President Zakir Hussain through family visits. A letter Shahid wrote prompted a visit to Nehru’s home when he was eleven. This inclusive, inquisitive upbringing shaped Shahid’s progressive worldview and laid the groundwork for his future poetry drawing from diverse cultures and traditions.

Manan, in his book, writes that Shahid also absorbed socialist thought and Western philosophers. His mother Sufia brought an amalgam of Muslim and Hindu traditions. His grandmother imparted Islamic teachings, while school exposed Shahid to Christianity and Western culture. This unique blend fuelled his humanist perspective transcending nationalism and religion.

During his teens, Shahid’s love for poetry grew. A gift from his father of a leather journal with the inscription to develop “discipline” marked a turning point. American poet TS Eliot discovered at college, profoundly impacted his understanding of impersonality and tradition in poetry. Time in America for his father’s PhD affirmed for him the beauty of Kashmiri culture. Returning to Kashmir, he became conscious of his lineage including prominent ancestors in medicine and education.

At the University

Entering Delhi University, Faiz further shaped Shahid. Though initially enamoured with Eliot, he later critiqued the politics and emotion in Eliot’s works. Throughout, the diverse influences of his upbringing seeded his poetry. The inclusive environment cultivated his progressive worldview and prepared him to assimilate disparate traditions into his distinct poetic voice.

Manan believes that Shahid’s formative years in Delhi from 1968 to 1975 proved pivotal in shaping the poet he would become. Leaving the familiarity of his affluent Kashmir upbringing for the first time, he entered a world ‘brimming with possibilities’. He revelled in ‘new experiences’ like the monsoon rains and developed friendships with fixtures of the Delhi literary scene.

Delhi, Manan writes, unlocked for Shahid both the wonders and complexities of the past. Captivated by the Mughal and British architectural legacy, he saw embodied in monuments like Jama Masjid the history missing from his textbooks. The imprint of the colonial experience and India’s syncretic cultural heritage left a lasting mark on his perspective. As a student, TS Eliot’s influence pushed him to interrogate tradition and impersonality in poetry. But witnessing first-hand the city of his birth also affirmed the need to capture the unheard stories of figures like Bahadur Shah Zafar.

Shahid realised the English language could be reinvented by infusing the richness of the subcontinent into poetic form. Though educated in English, his was not the Queen’s English – he leaned into the “biriyanization” of the language. The diverse stimuli of Delhi stirred in him both deep ambivalence about the legacy of British rule and a sense of belonging to the soil and culture of India. This pivot shaped the distinctive postcolonial voice that would soon emerge in collections like Bone Sculpture.

To America

As per the author, Shahid’s move to America in the 1970s proved crucial, placing him at the confluence of global diasporic literature. At Penn State, Shahid revelled in newfound freedom as a poet, lover, and reader. Though confronting cultural differences, his charm and humour won over many. Being gay, he refused to hide his sexuality but separated it from his poetry. For Shahid, Manan reflects, art’s value lay in itself, not the poet’s identity. This departed from confessional poetry’s conflation of poet and persona. He believed great poetry transcended propaganda or reductive readings highlighting ethnicity or orientation. His focus remained on crafting universal poems exploring loss and nostalgia.

At Penn State from 1975 to 1983, Shahid flourished as a poet despite distance from Kashmir. Writing relentlessly, he interwove memory and history to capture the richness of subcontinental culture in English verse. Though immersed in American poetry, he refused minimalism, instead expanding English through Urdu’s expressiveness. Rejections never deterred him; with each version, his poems improved. The resulting collection, The Half-Inch Himalayas, evoked nostalgia and exile, earning praise from Salman Rushdie.

For Shahid, Manan narrates, that art means process and perseverance. Penn State affirmed poetry as his calling, shaping the distinctive voice that would soon mesmerise readers across continents.

At Penn State, Shahid felt the absence of Faiz, barely known in America then. Obtaining Faiz’s blessing in 1980, he translated his work over the years, assisted by his mother. He aimed not for literal translations but to recreate Faiz’s poetic essence in English. This endeavour acquainted Western readers with Faiz while helping him absorb the Urdu master’s voice into his distinct idiom. Like his poetic ancestors, translating others expanded his poetic universe, enriching his vocabulary. Translation became a creative process, as he brought his lineage and roots into a new language.

Shahid’s time in the American Southwest shaped his poetry as well. The Arizona landscape evoked nostalgia, as he responded to its history and myth. Events like the Bisbee Deportation massacre stirred elegies lamenting injustice. Though the desert setting was new, his poetic perspective remained constant – distant yet empathetic. Poems memorialised deceased friends like Philip Orlando with composure, viewing pain as a formal feeling. As Shahid’s poetic concerns evolved, nostalgia and examining loss persisted. The Southwest environment provided settings to enrich his examination of memory and the burdens of history.

At Hamilton College, Manan writes, Shahid became a beloved, yet, demanding professor. Though sceptical of “creative writing”, he rigorously nurtured students’ poetic skills. He rewrote their poems ruthlessly, eliciting shock and frustration. But his meticulous, line-by-line edits aimed to push students further. Shahid scorned favouritism, inviting all to his lively dinners where poetry discussions flowed. He provoked through performance, playfully insisting students appreciate dead white males. He bound students in formal constraints to ultimately free them. His teaching philosophy aligned with his poetry – art meant process and hard work. Though at times controversial, he awakened students to language’s intricacies.

Shahid’s Friend

In 1987, Shahid’s friendship with James Merrill began and he started complimenting his early work. Over meals and visits, the two endlessly discussed form, rhyme, and word choice while revising drafts. Merrill opened Shahid’s eyes to formal poetry’s possibilities, steering him toward intricate structures like the canzone. Shahid absorbed Merrill’s aesthetic guidance, though their styles diverged. Merrill represented formal mastery and friendship without judgment. His presence lingered, as he paid homage referencing Merrill’s poems. Their bond expanded Shahid’s approach, helping unlock formal poetry’s potential to contain emotion.

Shahid aimed to reclaim the ghazal, disturbed by its misuse in American free verse by poets like Adrienne Rich. Raised in its oral traditions, he grasped its intricacies – disregard for thematic unity, formal features like radif, qafia, and recitation at mushairas. Shahid criticised vers libre ghazals for abandoning the constraints that liberate. He sought to convey the ghazal‘s essence through precise translations and adhered to its form in his compositions.

Drawing from Rilke to Ghalib, his couplets integrated diverse influences, nourishing the ghazal while renewing the tradition. Despite occasional errors, like confusing the ‘continuous ghazal’ with a qata in the introduction of his edited collection of essays on ghazal, Ravishing Dis Unities, he, Manan writes, expanded ghazal’s boundaries and showcased its potential in English, transforming perceptions in America.

Disturbed Home

In the 1990s, as the situation in Kashmir deteriorated, Shahid watched from afar in Amherst, Massachusetts. Appointed Director of the MFA programme at UMass Amherst in 1993, Shahid entered an intellectual hub, ‘befriending’ prominent thinkers like Edward Said and Eqbal Ahmad. Together, they denounced the backlash against Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses. Eqbal Ahmad became a fixture at Shahid’s lively dinner parties, where they intimately discussed global affairs, literature, and their homeland.

Meanwhile, in Kashmir, the situation changed rapidly. To suppress militancy, a fierce counter-insurgency was launched and it triggered a serious human rights crisis.

From afar, Shahid responded through his poetry. The Kashmir of his childhood, once an earthly paradise, had become a nightmare. In The Country Without a Post Office, he chronicled the violence rending his homeland. Eqbal Ahmad praised his ability to inform American readers about Kashmir. Through meticulous craft, he drew attention to forgotten stories. He transformed poetic language to capture injustice, Manan believes, as, Pablo Neruda did during the Spanish Civil War. His poetry insists that the stories of Kashmir’s human rights matter.

Manan writes that the Kashmir situation ruptured him from his childhood idyll. He chronicled his responses to a fast-changing situation in his The Country Without a Post Office, and expressed collective grief, lamenting injustices suffered by Kashmiri Muslims and the ‘exiled Pandit minority’. His poems uphold artistry over propaganda.

His Mother

Death shadowed Shahid’s poetry from the outset. His mother passing from brain cancer in 1997 devastated Shahid beyond compare. In the raw grief of his seminal poem Lenox Hill, he exposes his agony, measuring all sorrow against his immeasurable loss. Seeking consolation, he evokes the pathos of the Battle of Karbala in From Amherst to Kashmir, equating Sufia with martyred figures.

In verses summoning ghosts, he tried to grasp permanence. His elegy dignified his mother’s memory, channelling anguish into timeless couplets. Sufia’s light persisted through him, as he transformed mortal pain into immortal art.

Though dead twenty years, Manan writes, Shahid persists through his immortal verse. Tributes flowed after his passing, from global obituaries to a ghazal chain by over a hundred poets. Artists like Izhar Patkin and Masood Hussain visually rendered his poems. Archives at Hamilton College steward his prolific papers.

In Kashmir, recently, in a hypocritic twist, the institution that once turned its back on Shahid, denying him a job within its hallowed walls, then sought to reclaim a piece of his soaring legacy by conducting seminars on his life and work, now contemplate removing his poignant verses from their curriculum. As the poet’s fame soared, drawing admiration and recognition from all corners, the same institute sought to bask in his glory by organising seminars in his honour, eager to associate themselves with the luminary they once dismissed. Now they believe his poetry may foster a “secessionist mindset, aspiration, and narrative” among students.

Theme of Loss

Shahid’s poetry focuses on themes of loss, exile, and evanescence. His identity as an Indian, Kashmiri-American, or simply exile, Manan constructs, does not fully capture his extraterritorial nostalgia, which extends beyond geographic borders.

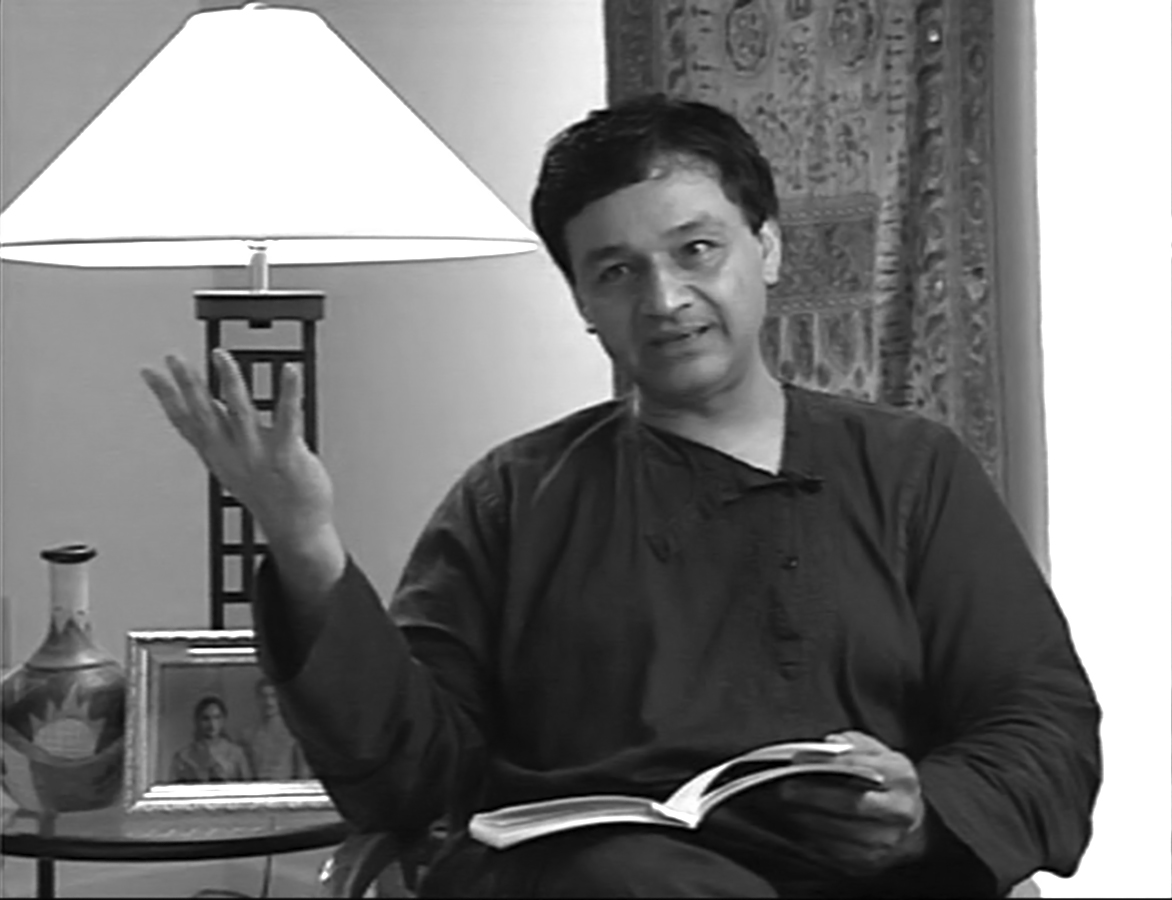

Manan Kapoor explores Shahid’s life as a doctoral student, a professor, a poet adamant about getting published in every journal possible, a friend, a translator and much more. It is supplemented with many never-seen-before images from the archives and personal collections of those who knew Shahid. It is filled with material gathered over conversations with family, friends, students, and colleagues, and Shahid’s unpublished essays.

The book is a biography of a poet’s life who embodied a diverse array of identities – a secular, Indian, Kashmiri, Kashmiri-American, elite, gay and lived most of his life in comfort away from the conflict destroying his home. Shahid was not a witness, perhaps an active listener to the news of destruction. He was not a refugee or an immigrant exiled from his homeland. But if it was not because of his poetry, there might still be a huge void in the world literature poetry about Kashmir. There are certain important aspects of his poetry that the book does not touch.

Shahid’s poems shift from recalling his childhood in India to overlaying memories of Kashmir onto American landscapes. As his awareness of universal transience grows, he turns to traditional poetic forms like the ghazal to provide structure amid rupture.

Critics link Shahid’s preoccupation with separation and disappearance and his formal innovations to creating stability within poems about loss. He employs intricate forms like the villanelle as temporary havens, housing evocations of the past. The ghazal’s recurring words and autonomous couplets mirror the paradox of independence and connection in human longing. This form suits his obsession with exile and the Gazelle’s cry for its accumulated losses.

As paradise and Kashmir blur, Shahid’s grief expands beyond personal loss. In later works he layers Kashmir’s devastation onto other global sites of suffering. Facing absolute rupture, he relies increasingly on poetic forms, which lend duration to themes of transience and desire for unattainable homes. His stanzaic “rooms” in the poem Rooms Are Never Finished has no ending, creating a perpetual exile within the text. Form becomes a way to temporarily elude the border of ending.

The Country Without a Post Office depicts Kashmir’s turmoil while memorialising its lost beauty. He maps Srinagar but also links Kashmir to war zones worldwide. Allusions and strict forms situate Kashmir within international modernism and various literary inheritances.

The Approach

Shahid’s transnational approach with poetry of witness, can isolate catastrophe. Instead, he creates a global network tied by formal resonances. His work aspires to Goethe’s concept of world literature as ethical creations that connect across boundaries.

Shahid’s poetics prefigure his revival of the ghazal form in America. Like The Country Without a Post Office, his ghazals mix traditions, avoiding prescriptions. Their autonomous couplets connected by refrain create wholeness through the fracture. This exemplifies his gift for conveying Kashmir’s nexus of memory and conflict through formal rupture. His polyglot, international representations keep Kashmir from being relegated to postcolonial or South Asian studies, insisting on its global relevance.

Shahid’s use of Emily Dickinson, whose short lines are embedded within his longer verse, creates a clash of styles. Dickinson’s cashmere becomes a way to play with the Western exoticisation of Kashmir. This intertextuality layers meanings and foregrounds discontinuity as part of his poetics.

He was not rigidly traditional. His ghazals embed political critique within tight formal constraints, using smooth structures to convey rupture. His reckoning with the ghazal’s Persian heritage was not cultural possessiveness but a means of disrupting ahistorical Western approaches.

Shahid’s poetics of rupture provide insights into representing crisis. For him, techniques like allusion and rigid poetic forms are politically charged, challenging perceived divides between poetics and politics, personal and political. His work demands recognising how extremity impacts poetry itself.

The post The Agha of English Ghazal appeared first on Kashmir Life.

from Kashmir Life https://ift.tt/nIFkuWr

via IFTTThttps://ift.tt/r4Vl85w

No comments:

Post a Comment