One of the many Europeans who immensely contributed to exploring, understanding and recording Kashmir was Sir Marc Aurel Stein, the great Sanskrit scholar, who not only translated Kalhana Rajatarangni but also compiled the folktales, write MJ Aslam

Sir Marc Aurel Stein is commonly known to Kashmiris and the world for his classic translation of the twelfth-century Chronicle of Sanskrit poet, Pandit Kalhana, Rajatarangini, “the river of kings”. Every scholar mentions interesting things about the eminent Hungarian scholar, explorer, archaeologist, and geographer.

Stein was born on November 26, 1862, to a Jewish couple, Nathan and Anna Hirschler Stein, in the Hungarian capital city, Budapest. Marc Aurel was his name and Stein was the surname of his mother’s father. As the Jewish religion did not allow Jews in those days to participate in European Christian culture and there were also obstacles in their way of getting an education in the educational institutions of Europe, Jewish families in Central Europe baptized their children in Christianity to get them exposed to European culture, education, and sciences.

Baptised to Christianity

His parents also baptized him to overcome the difficulties that he could have faced in his career. He was a great traveller too who visited the Central Asian countries and recorded his experiences in his letters to his brother Ernst Stein. He had a spectacular archaeological expedition into Chinese Turkestan in 1891, 1894 and 1901.

Stein had various geographical and archaeological tours of Kashmir and his book Memoir on Maps: Illustrating the Ancient Geography of Kasmir was published in 1899. This book was a Brahmanical narrative about the geography and archaeology of Kashmir, reproducing most of what he had already written as sub-text and notes of his Rajatarangini translation of which the first small edition came in 1892 the full version in 1900. It was in sharp contrast to all books written on the geography of Kashmir by other European explorers and scholars of sciences of geography and archaeology during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. It was not his geography book on Kashmir that earned him a name but his translation of Kalhana’s Rajatarangini that gave him recognition.

After mastering Greek, Latin, French and English languages at Kreuzschule University in Dresden Germany, Stein then graduated in Sanskrit and Persian at the Universities of Vienna, Leipzig. He received PhD in Sanskrit in 1883 at Tiibingen University. With laudatory commendations from Prof Rudolph Von Roth and Prof George Buhler, Stein had received a stipend from the Hungarian government to cover two years of postdoctoral research in Oriental languages and archaeology at the Universities of London, Oxford and Cambridge (1884-86).

Kashmir Sojourns

In 1887 when Stein was only 26 years old, he left home and came to India where he worked at Punjab University and Oriental College, Lahore for some time. Prior to that, he had visited Kashmir first in August 1888 and then he continued his visits to Kashmir till his last year of age, 1943.

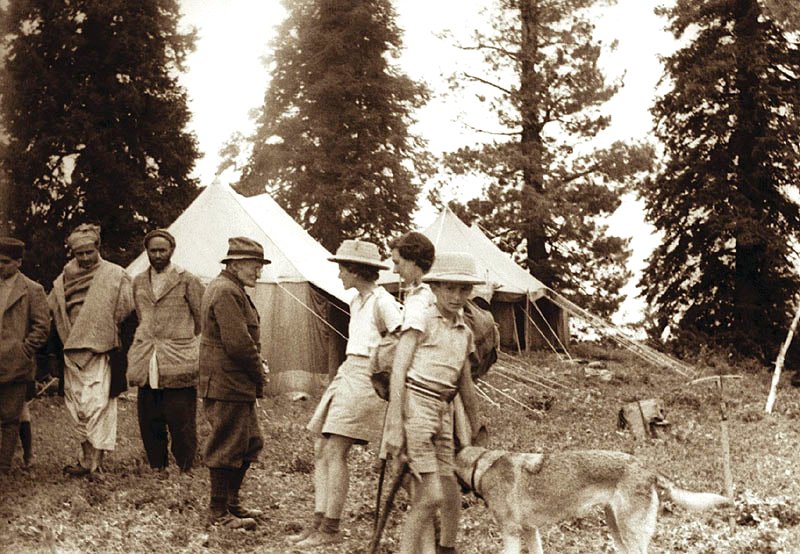

In summers he would come and often visit his beloved alpine meadow, Mahand Marg in Ganderbal where he would contemplate, think, read and write. He would pitch his tent there. A stream of letters also emerged from his pen from this beautiful meadow. It was here at Mahand Marg on July 4, 1895, when he wrote a letter to his brother that Prof Rudolph Von Roth had died in Tubingen. He was one of the main guiding and inspiring spirits behind his scholarly pursuits in studying Sanskrit manuscripts of Kashmir. The meadow covered with foot-high flowers, blue and yellow, looking like the most magnificent carpet in the world, looked gloomy to him due to the death of his mentor.

During his frequent sojourns to Kashmir – for the translation of Rajatarangini and compilation of geographical and archaeological expeditions, Stein had the company and “help” of well-known Pandit Sanskrit scholars of the time. These included Pandit Damodhar, Pandit Govind Koul and others who “came from morning to evening” to assist him. Pandit Govind Koul accompanied him at Mahand Marg where he was devoted to his Rajtarangini labours in the alpine seclusion of his cherished mountain camp. Koul‘s “erudition was to be essential to the translation and editing of the Rajatangini”. Pandit Govind Koul was a close friend of Pandit Isvara Koul who had partially prepared Sir George Grierson’s dictionary. He was of good use to him to learn the Kashmiri language and folktales too.

Hatim’s Folk Tales

Stein had developed a keen interest in language and folklore, especially Kashmir’s folktales. Although he was tied to time-consuming duty, working eleven hours a day on Sanskrit manuscripts, yet, after dinner, he would find time to pen down folklore tales from the mouth of a Kashmiri peasant bard, Hatim Tiliwoin.

A resident of Lar Ganderbal, Hatim was a peasant in the little hamlet of Panzil at the confluence of the Sind River and the stream draining Eastern Harmukh Peaks. Hatim Tiliwoin owed his surname to the possession of an oil press. He had fame throughout Kashmir’s Sind valley as Dastangou, a professional storyteller.

Hatim belonged to the family of Raweez, reciters, who had handed down these stories with verbal accuracy from generation to generation to their descendants. It is said that Hatim was the son of Sabir Tiliwoin who had handed down verbally a poem titled Yeli Forsyth Sahib Yarqand Zenini Gov (When Thomas Doughlas Forsyth went to conquer Yarqand), to his son, Hatim.

In the poem, Sabir gives a description of how he (Sabir), a barber, a carpenter, a blacksmith, a potter, a cobbler and a few others were “hired” from Sind valley villages, as labourers for the journey by the British team. It was a team of envoys of the Viceroy General, Lord Northbrook, for a diplomatic mission to Yarqand in 1873-1874. The team was headed by Thomas Doughlas Forsyth, and some surgeons and linguists. The arrangements for the camp of the Viceroy’s envoys at Srinagar were made by Maharaja Ranbir Singh. The mission was in response to the invitation of Ataliq Ghazi, ruler of Yarqand, who had lost Tashkand to Russia in 1865, for the enhancement of commercial and political interests between the British imperial government and Kashgar, and to stop Russian moves in the region.

The cited poem was recited in a song by Hatim Tiliwoin to Stein and Pandit Govind Koul. In the poem, Sabir repeatedly says that Thomas Doughlas Forsyth had come to “conquer” Yarqand. In the transcription of the Hatim’s Tales, Stein writes that Sabir’s song shows “it was a military expedition to conquer Yarqand”. But, on record, it was neither a military campaign of Thomas Doughlas Forsyth in 1873-1874 to conquer Yarqand nor Begar.

However, some well-known Kashmiri “academicians” have copied this comment of Stein verbatim, uncritically without probing into the historical record that the team comprised of the British envoys who were warmly welcomed by nobles and commandants of Ataliq Ghazi [Mohammad Yaqub Beg, d 1877] at Dadhkwah Yarqand. Hatim’s Tales transcribed by Stein with the assistance of Pandit Govind Koul had nothing to do with the history of Muslims of Kashmir or the State. Folktales cannot be a substitute for history, although fiction engages the human mind more than facts. Stein was not on any other mission in Kashmir to translate any other manuscript other than Kalhana’s Rajatarangini.

As such, Hatim Tiliwoin was mentioned and introduced to Stein by the people including Pandit Govind Koul. Pandit Govind Koul (b 1846) was the son of Pandit Balabhadra Kaul son of Pandit Taba Kaul. Theirs was a family of Sanskrit scholars who had a connection of hereditary Gurus with the Dhar family of famous Pandit Birbal Dhar of Kashmir.

After securing specimens both of the language spoken in the Sind Valley and of folklore texts, Stein invited Hatim to the mountain camp in the summer of 1898. Stein and his Pandit associate were “much struck by his intelligence, remarkable memory, and clear enunciation” on very his first recitation of folktales. His repertoire of stories and songs was a large one. Though wholly illiterate, he was able to recite them all at any desired rate of speed, which suited the ears and pens of Stein and his Pandit associate. Being a professional storyteller, Hatim was mostly called for performance at weddings and other festive village gatherings in the autumn harvest season. But, as it was harvest and the farmers were busy in their paddy fields, Stein found an opportunity to retain him for six weeks of the season.

Owing to the pressure of his work on Rajatarangini, Stein could not spare more than an hour in the evening, after dinner, to hear and pen down Hatim’s folktales in presence of Pandit Govind Koul. Besides Govind, Stein also took help from Pandit Gasi Ram. Besides, he also took the help of a phonographic recorder to understand the words he could not understand while stories were being orally recited in song form by Hatim in the airy camping place of the mountain. The stories were edited and published reluctantly by Sir George Grierson as late as 1923.

Mahand Marg

Thus, Mahand Marg is associated with the name of this great Hungarian man. There, he deliberated upon nature, read the MSS of Rajatarangini in the serenity of the mountainous meadow and also found time in the presence of Pandit Sanskrit scholar to translate folios of Sanskrit manuscripts. The Jammu and Kashmir Tourism department has recently raised a museum in his memory at Mahand Marg meadow.

Two men had guided his Sanskrit studies, giving him depth and focus, the finest understanding of scholarship. One was Prof Rudolp Von Roth, the reputed Professor of Indo-European languages at the University of Tubingen who had co-authored the Sanskrit-German Dictionary in 1875, commonly known as St Petersberg Lexion, considered the best achievement of the twentieth century in Sanskrit literature of the world. He also translated ancient Sanskrit texts.

The Rajatarangni Story

From a traveller’s account, Prof Rudolp Von Roth had come to know about the existence of an ancient Sanskrit MSS in Kashmir regarding Arthva Veda which needed to be explored. He wrote to British authorities and Sir William Muir, British Lt Governor of United Provinces, to locate it. Maharaja Ranbir Singh was contacted and in 1877, Ranbir Singh sent the said Sanskrit manuscript to Sir William Muir in 287 birch bark leaves held together loosely by a cord, which passed through a hole in the centre of each leaf.

Sir George Buhler, then Professor of Oriental languages in Bombay and master Sanskrit scholar, considered as the father of Indian palaeography, was urgently called to the viceregal lodge. He looked at the birch bark bundle of the Sanskrit manuscript which was trimmed and smoothed. He got the bundle bathed to clean it of dust and dirt in the bathroom. He assured Sir William Muir that the bath was not going to harm the manuscript or remove the ink. The bundle was laundered in the bathroom of Sir William Muir without affecting the writing on the birch barks. The manuscript was restored to a good shape and a local bookbinder was entrusted with the task by George Buhler to bind the leaves together. One week later the bookbinder sent it to George Buhler who sent it to Prof Roth.

George Buhler (1837-98) was a Professor of Indian philology and antiquities at the University of Vienna and an authority on Indian palaeography. He visited Kashmir in 1875 during the reign of Maharaja Ranbir Singh. All noted Sanskrit scholars of Kashmir contacted him and showed him Sanskrit manuscripts for examination. However, he was not shown the manuscript of Rajatangini fully. “Buhler was permitted only a glimpse of Rajatangini manuscript “before the owner took the manuscript away”. In his notes published in 1877, Buhler pointed out “numerous corruptions in all the Devanagari transcripts” and made it clear from a brief look of the manuscript that knowledge of Sharada script was imperative for translating Sanskrit manuscripts.

Sharda script was used by Kashmiri Brahmans and it was totally different from Devangiri script in which Sanskrit and Hindi were and are written in India. Devanagari replaced Sharda in Kashmir in the second quarter of the nineteenth century. George Buhler left Kashmir and India without having been given the manuscript of Rajatarangini.

In the colophons of the manuscript, Kashmiri Pandit Sivarama was mentioned as the representative of the Pandit family which alone had always preserved a copy of the Rajatarangini. Stein who was a pupil of George Buhler had heard about the whole story from his teacher and he had also read about it in Buhler’s published critical notes on Kashmir’s Sanskrit MSS.

Buhler had first established the existence of the Sanskrit manuscript and desired to translate it but he was not given possession of the codex. Then, he was called for other assignments to Viena where he remained extremely busy with other work.

William Moorcroft too had seen the manuscript of Rajatarangini during his Kashmir visit in 1822. Finally, destiny had it for M A Stein in Maharaja Pratap Singh’s reign to translate and introduce Rajatangini beyond Kashmir towards the end of the nineteenth century. Stein was able to get codex archetypes of all extant manuscripts of the chronicle. The Pandit who had denied George Buhler the manuscript had died already when Stein arrived on the scene.

The three sons of the late Pandit had cut and divided the manuscript into three parts. Stein’s endeavours and negotiations for the delivery manuscript bore fruit with the efforts of a Pandit who was a member of the State Regency Council and whose son was a pupil of Oriental College Lahore. He was supported also financially by the administration during his work on the Sanskrit manuscript and “ancient” geography of Kashmir.

In 1892, he first published the “critical edition” of the text of the Chronicle only. Then, in 1900 he published through Westminster, the text with commentated translation under footnotes of the Pandit Kalhana’s Shloks of the Kavya, titled Rajatangini.

It may be noticed that though he had devoted himself to the task of translating Kalhana’s Kavya in summers from 1888 to 1898, he had also, in between gone for archaeological and geographical expeditions in Kashmir from an ancient Brahmanical perspective. Besides, he also paid visits to India several times in connection with other academic and scholarly works.

In his long and comprehensive introduction to the chronicle, he has acknowledged his gratitude to Prof Buhler under whose guidance he had developed into a world-reputed Sanskrit scholar. He has highlighted the chronological and historiographical deficiencies of Kalhana’s metrical chronicle.

In 1901, after the completion of the translation of Rajatangini, he was appointed Inspector of Education by the British Resident in Kashmir to supervise the progress of education in Kashmir. Instead of taking the Kashmir education seriously, Stein set out on antiquarian searches in 1900-1901 and thereafter intermittently till 1930, in Central Asia, Kashghar, and Yarqand, Eastern Turkistan. He is credited with making several major archaeological excavations in the old cities of Khanates in the Xingjian province of China.

For British and Europeans he had unearthed the hidden archaeological treasures of the region, but Swedish author, Jan Myral, though known for his Maoist ideology, who travelled to Sinkiang region in 1976, has written that the Central Asian Muslims, Khojas of Turfan city, had a different perception about Marc Aurel Stein and other European archaeologists who travelled the region at the turn of the last century. They were all “thieves and spies. What else could you call men like Aurel Stein…….they travelled, researched and dug, and they were called scientists and they knighted and given medals and rewards. …… how could anyone explore countries, roads, and towns that had been known for two thousand years …… had traded with Europe long before Berlin or Stockholm or St Petersburg had even been thought about? We had cities when those were forests, marshes and wilderness”, Khojas of Turfan told him. They told him that “thieves” stole from them sculptures, paintings and precious antiquarian items.

Finally, Stein died unwed in Kabul on October 26, 1943. He is buried in the British cemetery of Sherpur Kabul, which was once Sherpur Cantonment of the British Army.

from Kashmir Life https://ift.tt/TMcCxtq

via IFTTThttps://kashmirlife.net

No comments:

Post a Comment